This story appeared in the February issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

In the human geography of New Orleans, only one sizable river-fronting neighborhood has had a substantial African American population consistently for two centuries. It’s on the West Bank, mostly within Orleans Parish, roughly between Opelousas Avenue to just over the Jefferson Parish line, and goes by various names today. The City of New Orleans officially calls it McDonogh (McDonoghville in adjacent Gretna), and while many locals view it as part of Algiers, others loosely conflate it with other neighborhoods in the shadows of the Crescent City Connection, such as Whitney and Fischer. In the early 20th century, the area got rebranded as Gouldsboro, but for most of the century prior, folks everywhere knew it as Freetown.

Freetown is traceable to one of the most famous names in New Orleans history, John McDonogh. Born in Baltimore in 1779 and apprenticed by a merchant, McDonogh arrived at New Orleans in 1800 and made a fortune importing everything from wine and liquor to tableware and hardware. By the 1810s, he sought a more placid lifestyle with safer investments, namely land, which brought his eyes to the bucolic “right bank,” the term at that time for the West Bank.

In 1813, McDonogh purchased the tract of Francois Bernoudy, where in 1750 Chevalier Jean-Charles de Pradel had built a lavish chateau known as Monsplaisir (see Preservation in Print, October 2020). The next year, McDonogh directed surveyor J.V. Poiter to lay out a grid of streets in what is now McDonoghville, making it the first subdivision on the West Bank, predating that of Algiers Point by a few years. In 1817, McDonogh made Monsplaisir his home, from which he lorded over a plantation spanning from what is now Homer Street up to Hamilton Street.

This rare 1922 aerial scene of today’s Central Business District and Lower Garden District (foreground, East Bank) captures Freetown and McDonoghville (left and center, respectively, across the river) at a time when much of the West Bank was nearly rural. Note McDonoghville Cemetery in left center distance. Detail of Army Air Corps photography, courtesy of Richard Campanella’s collection.

This rare 1922 aerial scene of today’s Central Business District and Lower Garden District (foreground, East Bank) captures Freetown and McDonoghville (left and center, respectively, across the river) at a time when much of the West Bank was nearly rural. Note McDonoghville Cemetery in left center distance. Detail of Army Air Corps photography, courtesy of Richard Campanella’s collection.

Over the next two decades, McDonogh incrementally expanded Poiter’s 1814 street grid, and in doing so, shifted the predominant land use from agrarian to urban (really more of a village). Small houses started to go up, with picket-fenced gardens amid outbuildings and fruit orchards. By 1834, everything from the riverfront to Hancock Street was laid out in squares, with streets parallel to the river named for American founding fathers, and those perpendicular named for thinkers, scientists and explorers whom McDonogh had admired. McDonoghville also had two parks, Mexico Square and Lima Square, and open space fronting the river, plus a canal running down the subdivision’s main X-axis, present-day McDonogh Street, draining runoff to the backswamp beyond Hancock Street. McDonoghville, in sum, was no slap-dash development; it was a thoughtful vision by a man who, in addition to being a self-made millionaire, was an armchair intellectual, a homespun philosopher, a budding humanitarian — and a large slaveholder.

Freetown was born of John McDonogh’s tortured attempt to reconcile those contradictory truths. As early as 1815, he rented lots at low rates to working-class leaseholders and sold land at reasonable costs to free people of color, forming the first free black settlement on the West Bank. In subsequent years, even as he continued to own and work his slaves, McDonogh educated those in his custody, devised various liberation schemes to return African Americans to their homeland, and granted freedom to many of those in his charge. Some became buyers of his property. According to an analysis of conveyance books by Algiers historian Kevin Herridge, McDonogh sold property to at least eight free women of color and 10 free men of color between 1827 and 1836, earlier records having been lost.

Advertisement

People he subsequently emancipated joined their brethren, and the community grew. It seems to have gained the nickname “Freetown” in the 1830s (which is about the same time Algiers gained its name), and in 1840, the sobriquet appeared in a Picayune advertisement in a manner suggesting it would have been familiar to readers. Indeed, the term was a common informal toponym used for enclaves of free blacks nationwide, and there were a number of other so-called “free towns” in lower Louisiana.

Like most neighborhoods in antebellum New Orleans, including those associated with African-ancestry populations such as the Faubourg Tremé, Freetown was demographically diverse. According to a census analysis by Algiers Historical Society member Tom Yalets, 120 free people of color lived in Freetown in 1850, making up nearly one-third its population; the remainder were whites who were, in descending order, German-, French-, Louisiana-, Irish- and American-born. Of the free black people, most had been born in Louisiana, though three were born in Ste. Domingue and two in Africa, the latter among the last living connections of African Americans in this area to their fatherland. It was probably in Freetown in this same year (1850) where writer Dominique Rouquette described how black residents gathered “almost every Sunday [to] have a game of raquettes,” a lacrosse-like sport of Choctaw origins, “of which they are passionately fond.”

From the perspective of human geography, Freetown is especially interesting for its position at the crest of the natural levee of the Mississippi River, a terrain valued for its elevation and access — and usually not home to black populations. Freetown’s desirable topography, which stands in stark contrast to the black settlement patterns of the East Bank, speaks to the influence of low population density on West Bank communities. High population density on the urbanized East Bank, whose natural levee was equally limited, made prime real estate very costly, such that disenfranchised people typically got relegated to the “back” of town, near the swamp. But on the West Bank, where people were few and land was abundant, there was enough high ground for everyone, even those forced into society’s lower echelons.

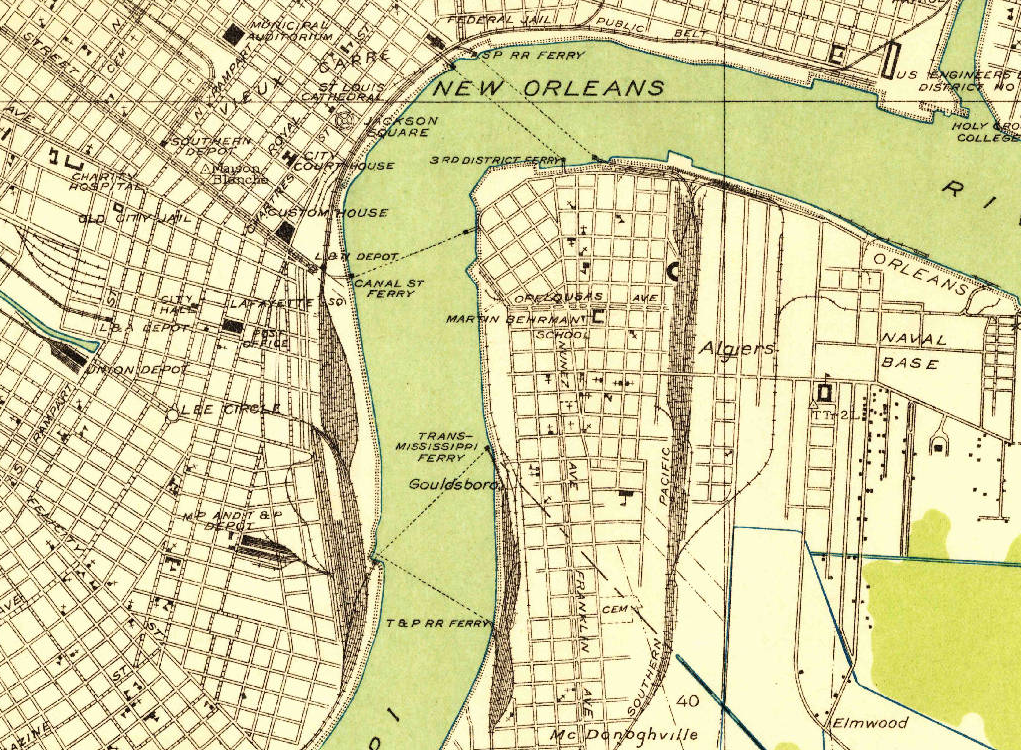

Because Freetown was a vernacular name, it rarely made it onto official maps and eventually faded from use, opening an opportunity for the area to be rebranded. This 1932 U.S. Geological Survey map used the name “Gouldsboro” (center) for the Algiers/Freetown/McDonoghville area, a reference to railroad tycoon Jay Gould, but it, too, would fall out of use. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Freetown grew substantially following emancipation, as former slaves arrived from regional plantations, and African Americans became the numerical majority in the community. Racial tensions also rose. In 1875, after a bloody shootout erupted between white and black neighbors, a New Orleans Times report, headlined “Battle Field Echoes — the Sunday Situation in Freetown,” described the community as “a village of about eight hundred inhabitants, situated on the right bank of the river, about two miles from Algiers and a half mile from Gretna. The population are mostly of the field laboring class — the blacks being in the majority five to one.”

In the 1880s, the Texas & Pacific Railroad launched the steam-driven transfer ferry Gouldsboro, named for company president Jay Gould, to get freight trains to Thalia Street across the river. Already laced with railroads, Freetown became that much more associated with train movements, and by the early 1900s, the area became known as Gouldsboro, and “Freetown” faded from the lexicon.

Advertisement

In time, “Gouldsboro” too would fall out of use (except for mariners, who still call this section of river the Gouldsboro Bend), and folks subsequently called the general area McDonoghville — or McDonogh for the older, mostly black section on the Orleans Parish side — else just Algiers. It remains an African American neighborhood today, the oldest of this size which is this close to the river, and boasts among the highest natural elevations on the West Bank. Its historic housing stock comprises shotgun singles and doubles, raised cottages, late-Victorian frame houses, bungalows and ranch houses, as well as some examples of early-1900s affordable housing: multi-family common-wall cottages, with four, six, sometimes eight units abreast.

John McDonogh’s life and death played out at either end of McDonogh Street in the community of his making. He lived at the river-end until his death in 1850. He arranged to be buried in the cemetery he laid out toward the rear, now known as McDonoghville Cemetery. McDonogh’s crypt is empty today, his remains having been removed to Baltimore, but its epigraph, as well as the surrounding tombs, speak to his legacy. “Study in your course of life to do the greatest possible amount of good,” reads one of the inscriptions in the marble. To that end, McDonogh bequeathed his fortune to the betterment of public education in Baltimore and New Orleans, giving rise to dozens of “McDonogh schools” and a fund that would last into the 21st century.

“Do unto all men as you would be done by,” reads another tomb inscription, one that perhaps informed his own soul-searching over bondage. Some of the African Americans he freed, and many former denizens of Freetown, are also entombed at McDonoghville Cemetery, near the tomb of the complex man with whom their histories are inextricably bound.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; Cityscapes of New Orleans; Bourbon Street: A History; and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or@nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements