This story appeared in the March issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Insurrections have consequences, even if they fail.

Louisianians learned this in 1768, after an attempt by colonists to rewrite the decisions of kings went woefully awry. But only in retrospect do the enormous urban consequences of that failed coup d’état come into relief — not just the usual “butterfly effects” of history’s contingencies, but direct changes in the course of our historical geography. At the very least, we’d have a whole different Uptown today if those conspirators never conspired — and who knows what the city might look like if they had succeeded.

To understand, we have to go back to March 1719, when city founder Jean Baptiste LeMoyne, sieur de Bienville, granted himself a vast land concession which included what are now the Audubon, University and Carrollton neighborhoods. In subsequent decades, Bienville leased or retroceded some of this land, and eventually sold or lost title to the rest. All the while, the lands were transformed, through enslaved labor, from forests to plantations, or habitations, a term that implied leased lands.

One ten-arpent habitation, in the vicinity of today’s Henry Clay Avenue, came under the management of Étienne Roy in 1723. After Roy died, his widow married a neighboring tenant, Sieur Jacques Hubert Bellair, who ran the eight-arpent habitation immediately downriver, along State and Nashville streets.

Advertisement

By this time, Pierre Benoit Payen de Noyan, the son of Bienville’s sister and her French lieutenant husband, had acquired the 21-arpent plantation above the Roy-Bellair property, extending through Audubon Park up to today’s Lowerline Street. According the 1763 census analyzed by historians Sally and William Reeves, Noyan had 78 slaves as well as 69 cattle, 80 sheep and 40 horses on this operation. The property later came under the ownership of Noyan’s son, Jean Baptiste de Noyan, namesake of his great uncle Bienville.

Further upriver in the mid-1720s, in what is now the Carrollton and Southport area, lived four additional families on concessions owned by Bienville and others. According to a 1927 Louisiana Historical Quarterly article, they were “Dulude, manager of the concession of Ste. Reyne and two children; Mr. Dubreuil, concessionaire, his wife and two children; Mr. Chauvin de Lery and three children; Mr. Chauvin de Lafreniere, his wife and three children; masters, 21; servants, 21; negro slaves, 385; Indian slaves, 11; horned cattle, 31; horses, 45, cultivated tracts, 800.” This area was known as the Chapitoulas tract, and the road to get there from New Orleans became today’s Tchoupitoulas Street.

In time, Jean-Baptiste de Noyan married the daughter of the aforementioned Nicolas Chauvin de LaFrénière, which put everything from Audubon Park through Carrollton under the control of one extended family, all of whom were deeply committed French subjects.

As for the Roy-Bellair property, it came into the domain of retired French infantry captain Balthasar de Masan (also spelled Balthazar Masan or Mason). Masan prospered from his enslaved plantation, and by the 1760s he had joined his neighbors in the ranks of the Creole planter elite.

Like them, Masan despaired to learn that, in 1762, King Louis XV of France had secretly signed the Treaty of Fontainebleau to transfer Louisiana to King Charles III of Spain. The main reason — to the keep the colony out of the hands of the British, impending victors in the French and Indian War — did little to placate French loyalists. As Spanish Gov. Antonio de Ulloa prepared to take control of Luisiana, resistance fomented among some planters who had done well under the old regime.

Among the discontented were our three big landowners in future Uptown: Nicolas Chauvin de LaFrénière, Jean-Baptiste de Noyan and Balthasar de Masan. They and others secretly met at Masan’s house to plan what many would call a coup d’état — or, alternately, what the narrative historian Grace King surmised had made Louisiana “the first European colony in America… proclaiming her independence.”

In the spring of 1768, the conspirators took action and succeeded in ousting Spanish Gov. Ulloa. But they failed to gain the support of the French crown to which they paid homage, and found themselves instead facing the wrath of authorities in Cuba. The Spanish responded by dispatching Gen. Alejandro O’Reilly and his army with orders to assert Spain’s rule over the rogue colony, which O’Reilly did with such alacrity that the word “Bloody” would get permanently attached to his surname. To wit, O’Reilly promptly rounded up the ringleaders, including LaFrénière and Noyan, and in late 1769, had them executed near the present-day Old U.S. Mint on Esplanade Avenue.

As for Masan and other accomplices, they were imprisoned, for 10 years to life, at the infamous Morro Castle in Havana. Pro-French New Orleanians later heralded the 1768 insurgents as “patriots,” and named a street “Frenchmen” near the site of their demise.

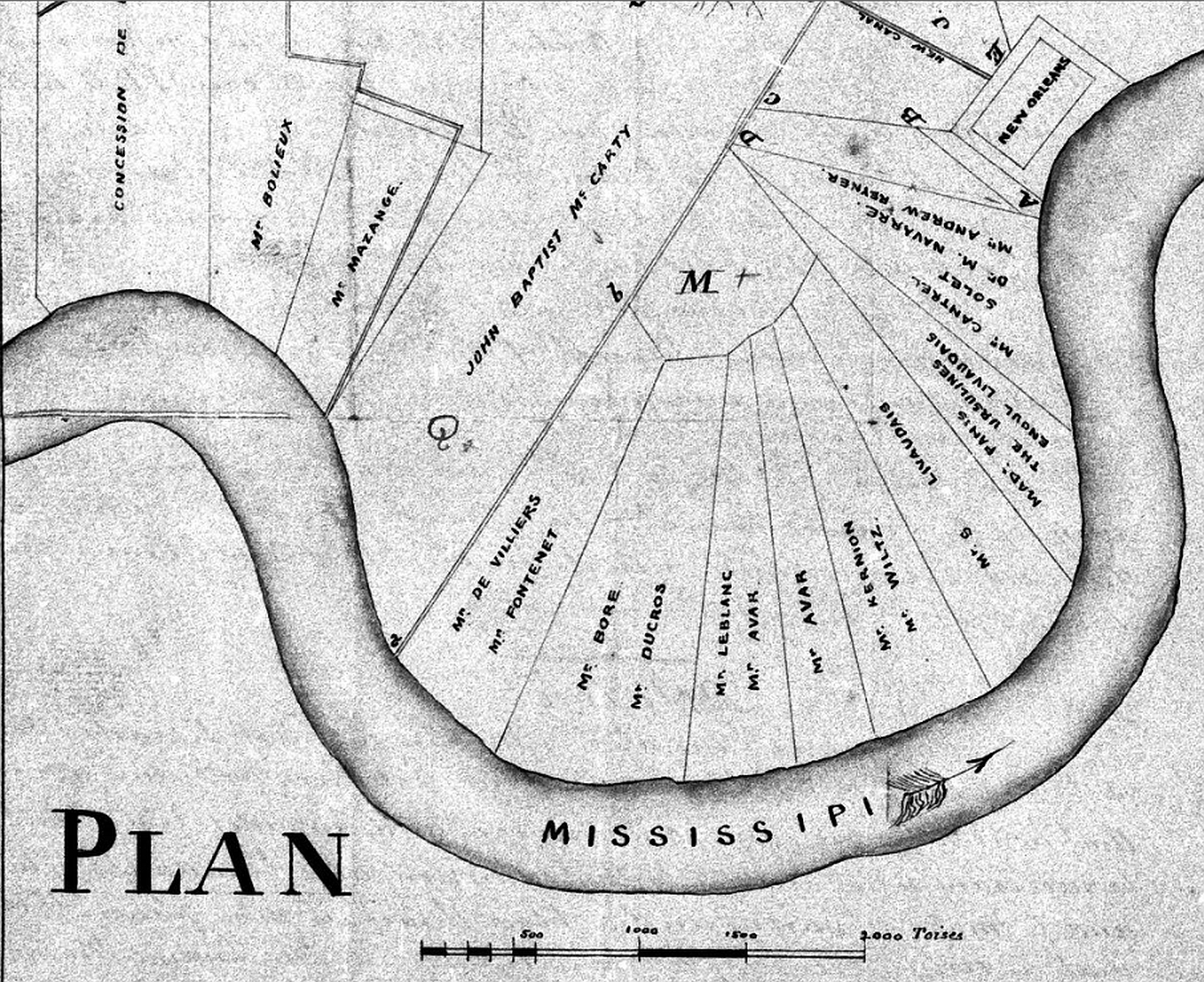

Most plantations visible in the left-center of this circa-1800 map had changed hands in the aftermath of the 1768 insurrection. “Detail of Plan of New Orleans — Lands from Concession De Debreuil to Bayou Gentilly” (1800) courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Patriots perhaps, but for those involved, the insurrection was a fiasco, resulting in death or banishment and the confiscation of their families’ properties. And it is in that last regard that the 1768 rebellion affected modern Uptown, as various lands would come under a completely new set of owners, who of course would make different decisions under differing circumstances regarding their destiny.

Consider Masan. His confiscated plantation came into the hands of Don Juan Lafite and Don Francisco Langlois, who, not incidentally, were both lieutenants in the Spanish military. In 1774, they sold the land to another powerful Spaniard, Juan Piseros, a successful merchant who was once a creditor to the Spanish government and a benefactor of Catholic missions in Texas.

In 1781, Piseros’ widow traded the property for a German Coast plantation owned by Jean Étienne de Boré. In 1795, De Boré’ gained fame for his successful experiments to granulate local sugar cane juice, which spurred cane cultivation throughout lower Louisiana, which in turn breathed new life into the institution of slavery. This breakthrough probably would have happened anyway, but the circumstances would have been different, as well as its profound ripple effects.

After De Boré’s death in 1820, the former Masan plantation had a number of subsequent titleholders, including the Burthe family, who had it subdivided in 1854 to become the neighborhood of today, through which runs Henry Clay Avenue.

Would that area look differently today had the Masan clan retained the parcel? You bet it would. A whole different sequence of people, exigencies and decisions would have played out.

Advertisement

Similarly, the two adjacent plantations, formerly of Noyan and LaFrénière, came under new owners. The future Audubon Park area pertained to the Fontenot and later the Foucher family, while most of present-day Carrollton became the property of the Macarty family, namely Jean Baptiste Macarty, also a Spanish captain and merchant.

The Fouchers decamped for Paris in the 1830s and left most of their tract undeveloped — that is, they never made the decision to subdivide. The Macarty family, on the other hand, sold their land to a group of investors who, in 1833, laid out the street grid of Carrollton, and built the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad to connect their subdivision with the city proper.

That railway, today’s St. Charles Streetcar Line, would establish the trajectory of future St. Charles Avenue and help catalyze Uptown development — “one of the earliest examples,” wrote architect Monroe Labouisse Jr., “of a transportation artery being the determinant of urban growth rather than its servant.”

As for the Foucher tract, it remained the only open land in the vicinity, which made it a convenient place to become Upper City Park in 1871 and host the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in 1885, followed by Audubon Park in 1886, Audubon Place and Tulane University in 1894, and Loyola University in 1910.

Would these areas look differently today had descendants of Noyan and LaFrénière retained the land? Utterly. In all likelihood, the present-day zoo, park and university campuses would have been subdivided, as all other adjacent plantations were — and what a different Uptown we’d have today.

This 1923 aerial photo of Audubon Park and the Carrollton area would look very different today had circumstances of the 1768 insurrection played out differently. Army Air Corps photo from Richard Campanella’s personal collection.

There were other, more personal consequences of 1768. The incoming Spanish regime introduced a new policy called coartación, by which slaves could purchase or arrange their freedom with their masters. “The sales of the estates of the executed or banished New Orleans rebels of 1768,” wrote historian Thomas N. Ingersoll, “provided the first opportunity for several slaves to test the new policy.”

Citing manumission records from 1770, Ingersoll found that the “Free mulatto Jean-Baptiste Horry purchased and immediately freed Antoine of Guinea, seventy-five years old, and Antoine’s wife, Marianna, fifty, from the estate of Balthazar Masan.” This record implies that a man presumably born in West Africa around 1695, and brought across the Middle Passage to Louisiana perhaps in the 1720s, finally attained freedom, along with his wife Marianna, as a result of Masan’s banishment for the 1768 insurrection.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Bourbon Street: A History, Bienville’s Dilemma and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements