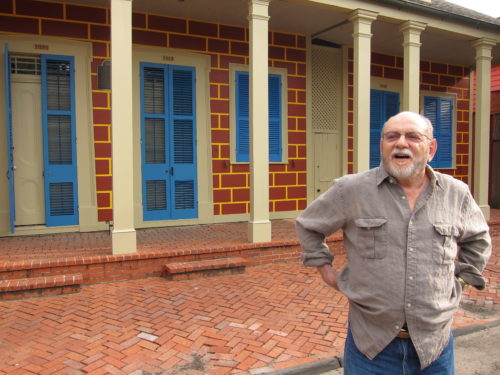

Gene Cizek is a preservationist, architect, Tulane professor and city planner in New Orleans. He resides in the Marigny triangle in a restored 1860’s Creole cottage.

This story is from the archives of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

You found your way into Faubourg Marigny in the late 1960s when it was really a forgotten neighborhood. What attracted you?

The neighborhood didn’t even have a name when I first moved here, it was just downtown. Originally I came to be near the Quarter, but when I crossed Esplanade I had this feeling that I had been here before. I felt at home. I wanted a really old house, but the main reason I ended up buying an 1808 Creole cottage on Kerlerec Street was because the owner would finance me for the $20,000 it cost. Back then, banks wouldn’t loan money for houses below Esplanade.

Explain the attitude that institutions had in the ‘60s and ‘70s about older neighborhoods like the Marigny, Lower Garden District, Tremé and Bywater.

City government and banks wanted to turn New Orleans into a “modern city” like Houston. Officials wanted to tear down Central City, for example, and fill the neighborhood with medium-to-high rise public housing. The Catholic diocese tore down the landmark church on Washington Square in Marigny and built the 10-story Christopher Inn. There were plans to build an elevated expressway through the Quarter and a Mississippi River bridge over Napoleon Avenue. The zoning laws in the old neighborhoods were modeled after post World War II suburbs. The Central Appraisal Board wouldn’t value the homes appropriately so you couldn’t get loans. The neighborhood was redlined until 1976 and I couldn’t get insurance because “there were too many old cars in front of the house.” There was zero protection for historic neighborhoods, so anything could be torn down. The prevalent attitude in the city was, “Why would you even care?”

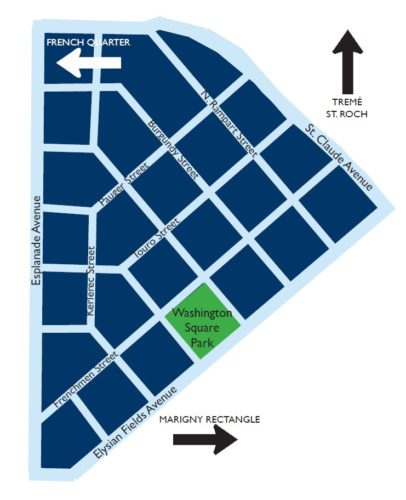

1 & 2: Views of the Marigny Triangle.

3: Gene Cizek in front of his Burgundy Street home.

You had degrees in architecture, city planning and urban design, and you were working on a PhD in environmental social psychology as well as teaching in the Tulane School of Architecture when you moved to the Marigny. And then you didn’t just live in the neighborhood, you lived the neighborhood.

I’ve been doing that for 45 years! In the late ‘60s there was a community renewal study of New Orleans that called attention to the Marigny Triangle, still just called downtown then, suggesting that it either be restored or leveled for medium-sized buildings to help reinvigorate the Quarter. Dr. Bernard Lemann had completed the first comprehensive neighborhood survey documenting the incredible architecture in the city, especially in the downtown faubourgs, and Harold Katner, the visionary director of City Planning, thought preservation was the better approach and asked if I would have my class study the triangle. We wanted to see if applying historic zoning, like in the Vieux Carré, to the neighborhood instead of the current suburban zoning would encourage renewal and help avoid more new construction like the Christopher Inn. At the time, there were no historic districts outside the Quarter so zoning was the only way to legislate. We rewrote the zoning code for the Marigny Triangle — taking into consideration the lot sizes, common setbacks, intimate scale and average height [less than 25 feet] of the buildings in the neighborhood — and the City Planning Commission and the City Council approved it. More people started thinking about living downtown after that.

1: The Marigny Triangle, delineated by Esplanade Ave., Elysian Fields Ave. and St. Claude Ave.

2: A Marigny home with a sign protesting proposed high rise development in the neighborhood in order to preserve the original architectural style of the neighborhood.

Who moved to the Marigny in those days, and who was already living there?

The neighborhood was very mixed; different ethnicities, lots of Germans and Italians, African Americans and Creoles, a real variety. There were chickens in many backyards. The Marigny has always been a resilient place, live and let live. Food stamps and Cartier within a block in the ‘70s. When I moved to Kerlerec Street, Terry Flettrich, who was a New Orleans icon as she played Miss Muffin on TV, lived in the house at the bend of Bourbon, and a very young Paul Prudhomme had a cooking school in her back building. About the same time I bought my first house here there was John Dodt, who worked for American Savings and Loan Association and helped finally get financing for renovations downriver of the Quarter; Bobby Moffett, an attorney who still lives here; Reverend Meyer of St. Paul Lutheran Church here; Cecil Burglass lived in the Claiborne Mansion on Washington Square and did the legal work to establish our neighborhood association. Gretchen Bomboy, Robyn Halvorsen and Ernest Jones were part of the original group; Kenneth Holditch, the Tennessee Williams expert and early Marigny pioneer, still lives on Frenchmen Street. Jean Stastny and Mitchel Osborne. Many more. We all just borrowed money any way we could to buy these houses.

What was the general condition of the Triangle then?

Up until the end of World War II, Frenchmen Street was a premier shopping district, but by the late ‘60s when I moved here a lot of it was vacant. There was an oyster supplier; a billiard table repair shop (where Marigny Brasserie is now) had previously closed down and that corner building was vacant; Snug Harbor opened in the ‘70s and the family lived upstairs (son Jason Patterson who now runs the jazz club said he grew up “in the shadow of Christopher Inn” because the 1960s building blocked the morning sun); what is now d.b.a. was vacant and then Theatre Marigny came; lots of the Frenchmen buildings were used as warehouses in those days. Where the Blue Nile is now was for sale in the early ‘70s for $30,000. There were some great places to eat like Martins Po-Boys on St. Claude and the Fairway Bar on Frenchmen, which was owned forever by a wonderful old couple. On the corner of Burgundy and Frenchmen was an old gas station from the 1920s that still offered curb service. Some of the wooden houses had rusticated stucco added to the façades in the 20s and 30s, I guess because it reminded the European immigrants of the old country. Part of the house I bought on Burgundy in 1976 had been a laundry for 50 years and the whole place was wall-to-wall termites. There were a lot of vacant houses just open to anyone off the street; stray cats lived in a house on Frenchmen Street right by a home that a couple had been in for over 50 years. I actually had my 30th birthday in a vacant house at 736 Frenchmen that was open to the wind, and four of us, all Scorpios, celebrated our birthdays but had to buy $1 million in liability insurance for the night because a guest might fall right through the floors.

So, basically, it was as dilapidated as today’s marginal neighborhoods where some leaders think it’s best to tear down the blighted homes. What is the most important advice you can give to people in emerging areas trying to create a walkable, safe and beautiful place to raise their families?

We’ve had to work very hard to bring this neighborhood to where it is today, and let me tell you, it never ends. You absolutely have to have a neighborhood association that is willing to protect and defend and go on the line for what they know is right. Everyday you have to be willing to fight against zoning violations and for better health and safety standards. You have to track abandoned properties and get the city to enforce codes. Being president of the Faubourg Marigny Improvement Association [FMIA] is such a hard job. Gary deLeaumont did it for six years and deserves sainthood, same for Chris Costello, who also served for six years. A wonderful young Frenchman from Paris, Alexandre Vialou, now serves as our president. He is married to a local lady. They have two beautiful children and live on Elysian Fields.

Of course, someone had to preserve all these old buildings before we got here or it wouldn’t be worth it. We’ve had to create some infill, but mostly a great stock of 19th-century houses was waiting for us. That’s crucial — that there hasn’t been too much demolition to change the character. We realized this early on, when we looked across Esplanade at the Quarter and saw that it had protection, while buildings on our side could be legally torn down. We formed the association in 1972 and I was the first president. Our priority was to become a National Register district, which we accomplished in 1974 with our boundaries increased down to Press Street to include the Marigny rectangle as well as the triangle. Then we went to work on becoming a local historic district so that we could get Historic District Landmarks Commission protection against demolitions and bad alterations. At the time, the state legislature had granted legal protection only to the Vieux Carré so we had to get attorneys to file papers and convince the local businessmen that it would be to everyone’s benefit to create a regulated district — and over the years it has proven to be very valuable to everyone. It wasn’t just in the Marigny; there was a real dedicated core of preservationists in New Orleans in the 1970s who wanted to save the city’s neighborhoods. Together we founded the Preservation Resource Center.

I recommend that neighborhoods organize tours and bring as many potential homeowners to see inside the historic homes. PRC tours of the Marigny really helped get people excited about the neighborhood. Once they got inside and saw the 12-foot ceilings and long windows and how close it was to the Quarter, yet still affordable, they started buying.

How did long-time property owners react to the new guys in the ‘70s?

If you bought a house and lived in it, you were immediately adopted by your neighbors. I had dozens of grandmothers and grandfathers. There was one couple who had inherited lots of rental properties in the neighborhood, and they came to a talk I gave called “The Mona Lisas of Marigny,” where I showed slides of the really beautiful architectural features of some houses. After the presentation, they came to me and said, “We own some of your Mona Lisas.” Over the years they hired me to renovate 13 of them. The businessmen’s association at that time didn’t want any restrictions on what they could build until they realized that businesses in the Quarter were making good money even though they had regulations.

Did you ever imagine Frenchmen Street would become one of the greatest jazz streets in America?

In 1971 we did a study that projected it as an entertainment district. Working in partnership with the business group helped make it happen. Snug Harbor opened in the ‘70s and that has been really good for the street. In 1990, the neighborhood association board went on a retreat and the result was a vision for the future called “Marigny 2000.” Part of that was Frenchmen Street as a bistro, nightclub and theater area. We put forth the legislation to make it a cultural and entertainment district.

Frenchmen Street at sunset. On the right, a musician plays the tuba in the window of the Spotted Cat Music Club.

Do you like what has happened on Frenchmen Street?

I like the open doors at night with life on the street, but the city needs to enforce the rules. The noise ordinance, liquor licenses, garbage, permitting: the city doesn’t always do as good a job as it ought enforcing any of it. The Faubourg Marigny Improvement Association has always been innovative, for example creating the Residential Density Overlay Zoning that encourages corner commercial architecture to return to neighborhood use, which then requires a strong working relationship between City Council, City Planning and other agencies. When they support the neighborhood needs and uphold the zoning and other laws, a higher quality of life is achieved.

Washington Square is a dream center for the neighborhood. Does the city maintain it?

The Faubourg Marigny Improvement Association takes care of Washington Square, not the city. When I moved here it was a dirt softball field for adults and all the finials had been torn off the iron fence so they wouldn’t hurt the players when they jumped for a ball. In 1976, with the help of Mildred Fortier who ran Parks and Parkways, we were able to get some money to renovate the square (from the same pot they helped neighbors in the Lower Garden District bring back beautiful Coliseum Square.) We just spent $15,000 refurbishing our historic iron playground equipment that the city put in a few years ago.

I gather from talking and walking with you Gene that staying true to a historic neighborhood isn’t a small commitment. What is the single biggest challenge today?

The greed problem. A buyer knows what they’re getting, but then they want to come in and overuse the neighborhood. The same problem has happened in the French Quarter and all over the United States: It is the uniqueness and the original qualities of a place that make folks want to live there, but when an area becomes too commercial then the land value goes up so much that residents can’t afford it anymore. Big, high rent condo projects do the same thing. We are not against new projects — a good neighborhood association has to be open to change and adjusting to meet needs — we are against people overusing the land. If you go higher than 50 feet in the Marigny, you block the views, the light, the breeze from the river, just like the Christopher Inn did on Washington Square 50 years ago. I am very worried about the precedent that will be set for the rest of the neighborhood if the 75-foot high Elisio Lofts are permitted. Particularly when I hear proponents cite the Christopher Inn as a precedent for new construction.