This story is from the archives of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

The impending end of New Orleans’ last daily newspaper, announced recently by the Times-Picayune to a shocked readership, has precipitated a citywide reflection on the role that this tactile median plays in civic life. Significant as it is today, that role was even greater in the 19th century, when local newspapers brought to New Orleanians the only consistent source of information about the outside world. Numerous editions in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian and other languages circulated weekly, semi-weekly, daily, sometimes twice a day, keeping informed, entertained, and agitated the people of New Orleans and the entire “Southwest,” as the Bee called it.

So important were print media in historic New Orleans that industry players spontaneously formed their own dedicated space within the city’s economic geography. Firms often cluster spatially to tap the resources, infrastructure, labor pool, services, data, markets and clients upon which all in the industry depend. “Concerns akin assemble together,” observed George W. Engelhardt as he surveyed downtown commercial activity a hundred years ago. Indeed they did: a banking district formed around the intersection of Royal and Conti streets, cotton merchants clustered around Carondelet and Gravier, wholesale grocers operated around Poydras and Tchoupitoulas, sugar and rice traders held court at North Peters and Customhouse (Iberville), theaters abounded around Canal and Baronne, and anything that involved the printed word could be found, from the 1840s to the 1920s, on Newspaper Row: the 300 block of Camp Street plus the adjacent alleys of Natchez, Bank, and Commercial.

Early print media first set up shop seven blocks downriver from that location, in the French Quarter. Francophone professionals of various stripes worked on or near upper Charters Street, among them the city’s first generation of newspaper editors and printers. The settlement of Anglophones across Canal Street in the upriver faubourg of St. Mary, and their subsequent commercial investments in the so-called American sector, would change this pattern. While all seven of New Orleans’ editorial and printing offices were located in the French Quarter in 1809, only four of 10 remained there in 1838; all others had opened uptown. City directories indicate that, in both relative and absolute numbers, the geographical center of gravity of the New Orleans publishing scene had largely shifted from the old city to Faubourg St. Mary by the mid-1840s. What tipped the balance was the arrival of a new player in the industry.

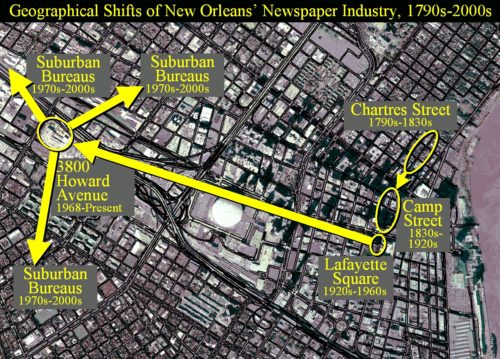

1: A map chronicling the geographical shifts of New Orleans’ newspaper industry from the 1790’s, where it began on Chartres St. to the 2000’s, where it is located at 3800 Howard Ave.

2: The distribution of newspaper offices in New Orleans in 1895 along Newspaper Row and the nearby area.

Volume 1, Number 1 of The Picayune hit the cold, rainy streets of New Orleans on January 25, 1837. Its proprietors first set up shop in a 12-by-14-foot room at 38 Gravier, and relocated a few months later to slightly more spacious quarters at 74 Magazine. Before completing its first year, the operation moved once again to 72 Camp St. , where it was the only newspaper operation on that street (although five other papers and journals functioned within a few blocks). Around this spot on Camp Street (renumbered to become the 300 block), New Orleans’ most famous newspaper would prosper for more than 80 years, and attract colleagues and competitors to its flanks.

On February 16, 1850, disaster struck as a conflagration consumed the Picayune office and 22 adjacent buildings. The smoke cloud, however, had a silver lining: the cleared area allowed the publishers to purchase the lot and construct a custom-made building at 66 Camp to suit its needs. Builders Jamison and McIntosh finished the handsome four-story Greek Revival structure by late 1850, making it the first plant erected by a newspaper in the city. There was no mistaking the office of The Picayune: a copper eagle perched dramatically upon the prominent parapet, an ornate iron-lace verandah lined the second story, and in between was etched into the façade the newspaper’s name. Because the depth and common walls of the building restricted natural light, the architects designed a glass sunlight on the roof and painted the interior white for the benefit of the 80 or so employees inside. The building was also fitted with a steam elevator, a dumbwaiter, a network of gas jets and three Hoe cylinder presses powered by a coal-burning steam engine, all of which were made in New Orleans. The Picayune’s commercial success and commanding location drew competitors nearby. By 1854, four of the city’s 15 newspapers and periodicals were located on Camp Street, while another seven operated nearby. Only three remained in the old city, and one in the Faubourg Marigny.

1: 300 block of Camp Street in downtown New Orleans, the heart of Newspaper Row from the 1840s to the 1920s.

2: This Newspaper Row back alley bustled with so many orphaned newsboys awaiting the latest edition that the Sisters of Mercy of St. Alphonsus opened an orphanage for them. It operated at 20 Bank Place, now 324 Picayune Place, currently one of the quietest public spaces in downtown New Orleans.

3: Natchez Alley, along with Commercial and Bank alleys, hosted dozens of enterprises working every aspect of the publishing industry. To commemorate the industry, Bank Alley was renamed Picayune Place a few decades ago.

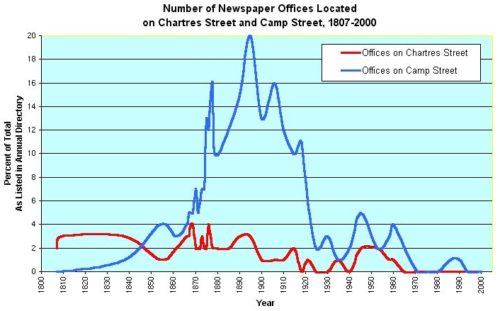

Why Camp Street? Like Chartres in the French Quarter, Camp was as busy as any street in Faubourg St. Mary. The blocks between Gravier and Poydras, where most publishers settled, were centrally located between the new uptown faubourgs and the old city, while not too close to the bustling riverfront nor the destitute back-of-town. Major banks, hotels, and offices occupied adjacent blocks, as did City Hall, which in 1853 relocated to nearby Lafayette Square. There were no compelling reasons not to locate on Camp Street, and plenty of reasons to locate there, namely the presence of major players in the industry, starting with The Picayune and later The Times-Democrat, Daily States, City Item, Daily News and others. The success of the early-comers to Camp Street, who may have selected the site largely for incidental real estate reasons, lured rivals for the simple survivalist instinct to be in the heart of it all, especially in a competitive information-dependent business like journalism. Once a critical mass was reached, support services such as printers and binders also settled in the area, which iterated the trend. It should be noted, however, that a Camp Street address was by no means critical to the success of a newspaper. While it had more newspapers and publishers than any other street for most of the years between the Civil War and World War I, Camp Street never had more than 57 percent of all such offices in the city, averaging about 35 percent between 1870 and 1918. Still, those who called Newspaper Row home tended to be the highest-circulating and most influential papers.

A visitor walking up Camp Street from Canal in the mid-1880s would have sensed Newspaper Row before seeing it, from the scurry of newsboys and the sounds of their singsong sales pitch. To his left, on the riverside corner of Canal, he would have noticed the first Camp Street print shop, above which was published the Louisiana Sugar Bowl and Farm Journal. After passing the City Hotel, he would encounter a composing and printing shop at 28-30 Camp, indicative of Newspaper Row’s ancillary businesses of job (contract) printing for things like business cards, fliers, pamphlets, directories and books. The corner shop at Gravier and Camp was also occupied by a hand-printing business (type set by hand), while a job-printer shop with a press room ran a few doors down on Gravier. The third and fourth floors of 56 Camp were utilized by a hand printer and bindery, respectively, while all floors of 58 Camp were occupied by one of the largest-circulating papers in the city, The Times-Democrat, an operation running straight back to Bank Place. The Picayune, headquartered prominently at 66 Camp (now 326 Camp), had its offices, composing rooms and press rooms spread out across all floors and a number of adjacent buildings. If the windows were open, the clicking of hand-set type may have been audible, until they were replaced in the early 1890s by noisy but efficient linotype machines. Directly across the street, at the intersection of Commercial Place, were the offices of the Louisiana Sugar and Rice Report (61 Camp) and the Soards’ Business Directory of New Orleans. Back on the river-side of the street, the building at 68 Camp was home to The Mascot, while the rear of the building at 72 Camp was the cramped office of the Evening Chronicle. There may have been a cluster of paper boys gathered across this narrow alley, at the door of the Newsboys’ Home, biding time until the latest edition came off the press by rolling dice, racing each other or playing ball in Natchez Alley. Insurance offices and banks, which often patronized the print shops, filled the storefronts and upper floors in between. After crossing Natchez Alley — home to the main office of the City Item, the Southwestern Christian Advocate, lithographers, paper warehouses and printers — our visitor would pass yet another print shop and the 90 Camp office of the major Daily States. Three more publishing-related shops, plus The Southwestern Presbyterian, The Baptist Advocate and The Orion, occupied portions of buildings in this block before Poydras Street. Above Poydras, the visitor might notice a number of smaller shops — the influential German Gazette, The New Orleans Christian Advocate and Der Familien Freund between 108-112 Camp. By the time our friend made it to a park bench at Lafayette Square, he would have had plenty of opportunities to pick up some reading material.

Newspaper Row’s heyday peaked in 1890-1910, when over 20 of the city’s 50 or so publishing-related offices (and almost all of the major ones) operated with two blocks of the Camp/Natchez intersection. The tight cluster of aggressive journalists made for a bustling and colorful atmosphere, one that sometimes boiled into brawls and shoot-outs. Mostly, though, the row buildings were filled with diligent journalists, editors, typesetters and workers intent on meeting deadlines and surviving in the fiercely competitive market. The streets around Newspaper Row were the domain of newsboys, most of them orphans, on whom the papers depended for distribution before trucks and vending machines. The number of street urchins was such that, in 1879, the Society of St. Vincent de Paul and the Sisters of Mercy of St. Alphonsus moved their newsboys’ home to 20 Bank Place (now 324 Picayune Place), directly behind the Picayune office, where homeless newsboys were availed the services of a school, dormitory, kitchen and chapel tucked among three floors that were also used for warehousing.

1: A graph depicting the rise and fall of Newspaper Row according to the numbers.

While the industry remained geographically stable, its constituents opened, closed, changed hands, or merged relentlessly, a sign of changing times in an increasingly complex industry (and a precursor to today’s situation). “From the simple operation it had once been, newspaper publication was [becoming] a highly specialized and tremendously costly manufacturing process,” wrote journalist and author Thomas Ewing Dabney in 1944. “Machinery grew larger and more expensive; telegraph tolls increased; the cost of news service rose; paper; ink; and other materials climbed; so did labor.” A major merger occurred in 1914, when the Picayune consolidated with the Times-Democrat (the product of an 1881 merger of the Times and Democrat) and became the Times-Picayune. Now owned by the Nicholson Publishing Company rather than the Nicholson family, “the Old Lady of Camp Street” became a corporate entity. With so many papers swallowed up by rivals or hobbled by war-time costs, the number of offices on Camp Street dwindled from 16 to 10. The Newsboys Home on Bank Place closed in 1917. After World War I, the rapidly expanding Times-Picayune decided to relocate its main office to a larger building on Lafayette Square near City Hall.

The postwar era saw the demise of a number of old industry clusters in downtown New Orleans, and publishers were no exception. The concurrent demographic diffusion to new lakeside neighborhoods and later to suburban parishes motivated the Picayune to relocate once again, in 1968, to a spacious new facility at 3800 Howard Ave., largely for its convenient access to new transportation arteries. Following the spatial dispersion of the readership, the Times-Picayune established six regional bureaus and commenced publishing spatially specialized supplements, from the Westwego Picayune to the Slidell Picayune, from the River Parishes Picayune to the St. Tammany Picayune, and from the Uptown Picayune to the Downtown Picayune. The paper’s recent announcement to end daily service constitutes the latest chapter in this story of eternal change, and certainly not the last one.

1: The heart of Camp Street’s Newspaper Row viewed from the top of the Place St. Charles skyscraper in 2003.

2: Old ad for engraving and lithography, Exchange Alley.

The era when “concerns akin” benefited by “assembling together” has passed for most industries in most cities. New Orleans’ cotton district, sugar and rice district, Chinatown and the wholesaling district, to name a few, are now all relic cityscapes. Yet spatial clustering still bears fruit for certain lines of work. Consider, for example, the recent success of local entrepreneurs in establishing shared workspaces, oftentimes in the surplus office space left behind when the white-collar oil and gas industry decamped for Houston. Incubation centers such as the Idea Village, New Orleans Exchange, Icehouse, Launch Pad and the New Orleans BioInnovation Center endeavor to share fixed-cost assets, reduce risk, network socially and intellectually cross-pollinate — ingredients for success that all hinge on spatial proximity. Witness also the impact of overlay districts, a zoning tool designed to encourage certain commercial land uses in a targeted area, which have led to the blossoming of new eateries on Freret Street and the clustering of building-materials recyclers on St. Claude Avenue. Note also the success of the medical district along Tulane Avenue, the government services district around Loyola Avenue, the entertainment districts of Bourbon and Frenchmen streets, the new guerrilla galleries and performance spaces on St. Claude Avenue, and the forthcoming rebirth of the theater district — all of which benefit from walkable proximity among competitors.

As for Newspaper Row, we are at least fortunate to retain most of its old buildings. They line the 300 riverside block of Camp, the narrow Picayune Place (formerly Bank Place) behind it, and on adjacent Natchez Alley. Only one clue of former occupancy remains visible from the street: the faint palimpsest of THE PICAYUNE etched into the upper façade of 326 Camp. Ironically, with all the recent turmoil at the Times-Picayune, its journalistic activity will soon shift back to its historic location. After decades on Howard Avenue, a site chosen for distribution reasons, the Times-Picayune plans to shift much of its Internet news-gathering activity to the downtown office of nola.com, not too far from old Newspaper Row.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Bienville’s Dilemma, Lincoln in New Orleans, and other books. More about Newspaper Row and other industry districts, including the sources for this article, may be found in his 2002 book, Time and Place in New Orleans (Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna, Louisiana). Preservation in Print is honored to feature a series of articles by Campanella beginning with this issue. He may be reached at rcampane@tulane.edu.