This story appeared in the April issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

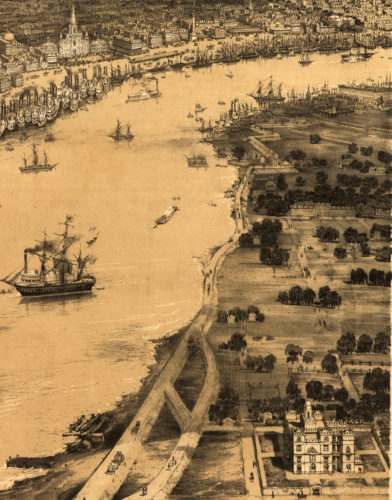

Passengers on a Mississippi River steamboat passing through New Orleans in the mid-1800s would have been dazzled by many sights: the ballet of vessels maneuvering within one of the world’s busiest ports; church steeples and hotel domes in the South’s largest city; the sprawl of urbanization feathering into the cane fields and forests of the American subtropics.

Their eyes also might have noticed a replicating architectural curiosity along the skyline, from Carrollton to Harvey, Gretna, Algiers and the Third District: imposing castellated structures evocative of the citadels of the Old World, picked up and dropped along the lower Mississippi.

One early example of “the castle look” came in the form of the car barn for the New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad, today’s St. Charles Streetcar Line. The pavilion’s façade had crenelated towers connected by a long battlement above Gothic apertures. The bold design likely aimed to give a sense of destination and importance to the new subdivision of Carrollton, whose backers were also investors in the rail line.

The area’s biggest “castle” was the U.S. Marine Hospital on the McDonoghville (later Gretna) riverfront, built in 1834 as part of the Marine Hospital Service, an early federal health law providing care for infirmed American seamen. Spanning 160 feet in width and nearly as high, the sanatorium featured Gothic fenestration and crenellation all around its various turrets and battlements, culminating in a high central tower.

The first U.S. Marine Hospital, bottom right, was located on the McDonoghville (later Gretna) riverfront. Built in 1834 as part of the Marine Hospital Service, it spanned 160 feet in width and nearly as high. The Belleville Iron Works, upper right, sat on the Algiers riverfront. Image by John Bachman, 1851, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

It was one of the most salient landmarks on the West Bank horizon — until its spectacular demise. Used by Confederates to store 10,000 pounds of gunpowder, the hospital “blew up with a report that shook the whole city to its foundation stones,” reported the Daily True Delta on Dec. 29, 1861, shooting “a pillar of flame…up to the sky, for an instant illuminating the whole heavens… [It] must have been the diabolical work of some incarnate fiend, [of] traitors in our midst.” Utter obliteration resulted; even “the trees in the yard were broken, twisted and stripped as if by a hurricane.” After the war, the Marine Hospital moved Uptown, to Tchoupitoulas Street and Henry Clay Avenue, where its latest circa-1930s incarnation, also a prominent riverfront landmark, has been recently integrated into Children’s Hospital.

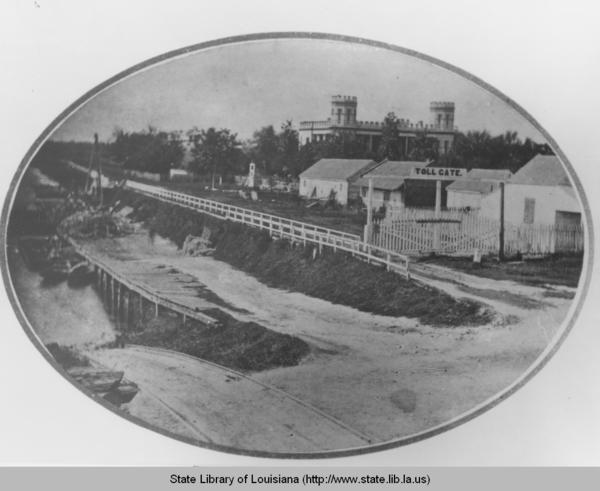

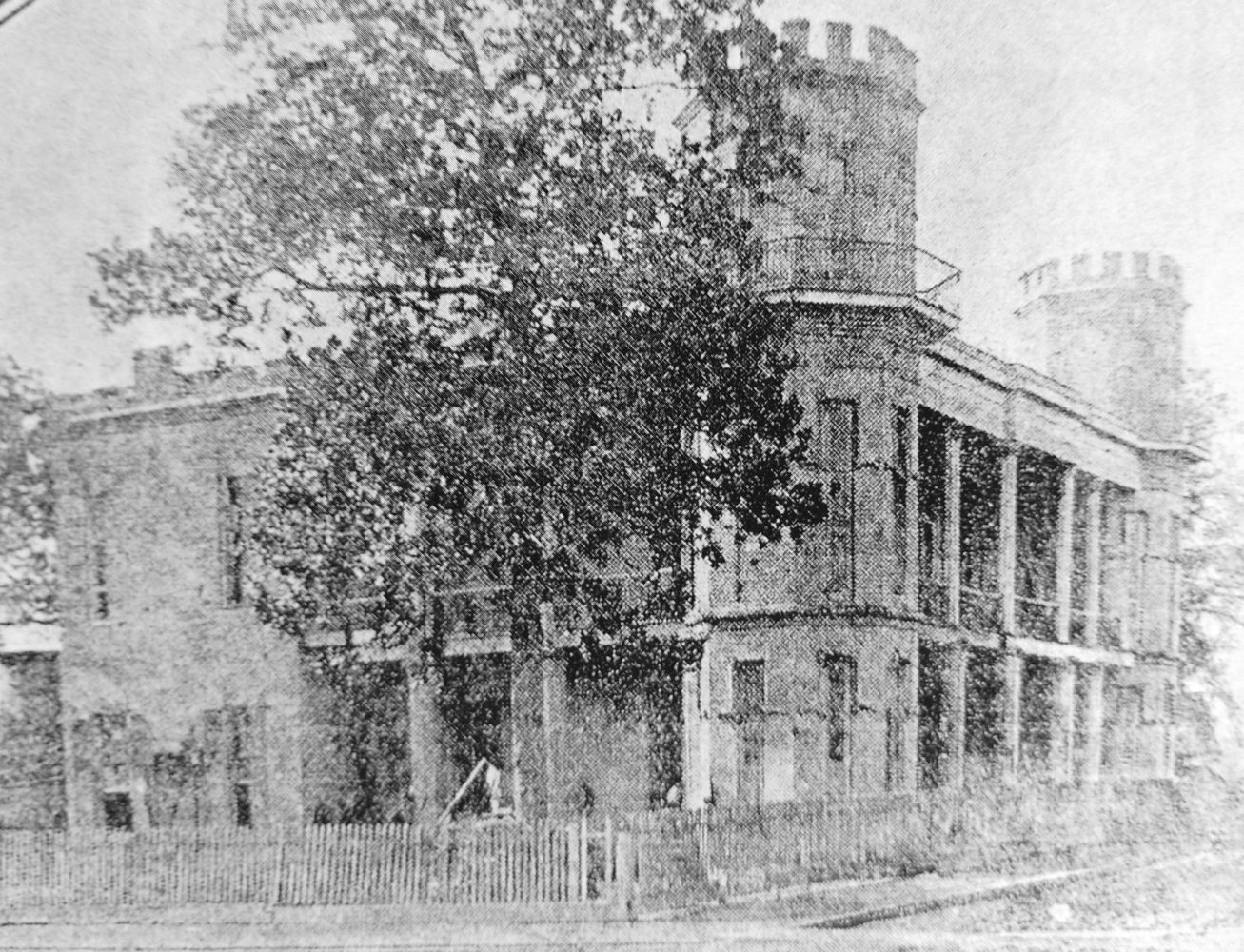

Perhaps the most famous riverfront “castle” earned exactly that sobriquet, “Harvey’s Castle.” Built on the upper flank of the Destrehan (now Harvey) Canal in 1846, this manse was the home of Louise Destrehan, daughter of canal owner Nicholas Noel Destrehan, following her marriage to Captain Joseph Hale Harvey. A family descendant described the house as a “medieval, two turreted baronial castle patterned from a faded old picture of [Joseph’s] grandfather’s and great uncle’s home in Scotland.” Inside were marble mantels, walnut finishing and winding staircases up the crenelated octagonal towers. Patriarch Nicholas Noel Destrehan had previously built a comparably lavish home for himself, nicknamed “Destrehan’s Castle” and the “Louisiana Lyceum and Museum” for his collection of art and curios, an eccentric touch that also earned the house the nickname “Destrehan’s Folly.” It burned in 1852.

This photograph from the early 1900s shows Harvey’s Castle and the marine railway and terminal at the Harvey Canal. Photo courtesy of the State Library of Louisiana Historic Photograph Collection

Harvey’s Castle, which served as the Jefferson Parish Courthouse from 1874 to 1884, survived until 1920, when the U.S. Government demolished it to widen the Harvey Canal after it became part of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway.

Industry also liked the castle look, to project a sense of strength and reliability. The best example was the Belleville Iron Works, established by John Whitney on the Algiers riverfront in 1846. Covering 150,000 square feet and employing 300 men, the Belleville foundry made steam engines, boilers, specialized parts for sugar mills and cotton presses, and brass and iron castings for ship-building. Its main building comprised two enormous pavilions with massive brick walls fronted by crenelated towers said to emulate Penrhyn Castle in Wales — all so prominent that people nicknamed the entire neighborhood “Belleville.” The foundry lost its customer base during the Civil War, and, under different ownership, burned down in 1883. The site sits today at the intersection of Patterson and Belleville streets.

Built on the upper flank of the Destrehan (now Harvey) Canal in 1846, Harvey’s Castle was the home of Louise Destrehan, daughter of canal owner Nicholas Noel Destrehan, following her marriage to Captain Joseph Hale Harvey. A family descendant described the house as a “medieval, two turreted baronial castle patterned from a faded old picture of [Joseph’s] grandfather’s and great uncle’s home in Scotland.” Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Fire was also the fate of the short-lived but truly spectacular Touro Alms House in today’s Bywater, funded by the estate of famed philanthropist Judah Touro, who died in 1854. The executors of Touro’s will offered $500 for the best architectural design accommodating up to 450 pensioners. “When completed,” predicted the Picayune, “the Touro Almshouse will be one of the most noteworthy edifices of our city — a monument to…its immortal founder.”

The winner, announced in January 1859, was William Alfred Freret Jr., who conceived a huge three-story masonry compound featuring two crenellated four-story towers and ornate walls topped with parapets and pinnacles. It was majestic, quite English and emphatically Gothic.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, it neared completion at an inopportune time: April 1862, as Captain David Farragut’s Union fleet gathered in the Gulf and readied to enter the Mississippi and seize Confederate New Orleans. By May, Union troops occupied the Touro Alms House as a federal base and bunkhouse.

Three years later, on the eve of their withdrawal after the Confederate surrender, resident troops baked beans in a makeshift oven they had hooked up to a flue intended for ventilation. Sparks rose to the roof and ignited. By dawn Sept. 2, 1865, Judah Touro’s Gothic castle collapsed into a pile of smoldering ashes. Its form and style, however, lives on in one of William Alfred Freret’s other works, the Old Louisiana State Capitol in Baton Rouge, perhaps the best surviving example of its type.

The heyday of the crenelated riverfront castle was the 1830s to the 1860s, but the “castle look,” cloaked in Gothic or Romanesque attire, made a local resurgence in the 1890s, only this time for large downtown buildings. The most astonishing example was James Freret’s Masonic Temple on the corner of St. Charles Avenue and Perdido Street. The cousin of the aforementioned William Alfred Freret, James Freret designed something of a cross between a castle and a cathedral — the Picayune called it “fourteenth century Gothic”— and topped it with a spire and statue of Solomon. Dedicated in June 1892, the Masonic Temple broke the downtown skyline with its peaked roof and dormers, intricate friezes, towering ogive windows, octagonal spire and five-story corner bartizan (turret or tourelle).

Imposing as it looked, the building had structural problems, and had to be replaced in 1921 with a Modern Gothic-style building temple, now a hotel.

Advertisement

Similar was the fate of the equally impressive Old Criminal Courthouse (1893), designed by Max A. Orlopp Jr. in the Richardson Romanesque style on what is now the corner of Loyola and Tulane avenues. Orlopp’s creation, according to a Picayune columnist, “reminds one of an old-time chateau or Norman country house, [with] circular towers rising in the center…castellated, with turrets, battlements and slits for the archers.” High above was a reconnoitering clock tower visible for miles. Like the Masonic Temple, the courthouse had structural problems, and had to be dismantled during the 1940s. Its former site is now occupied by the main branch of the New Orleans Public Library.

Two years after the construction of the Old Criminal Courthouse, 10 blocks in Algiers Point were incinerated in a neighborhood inferno, including the old Duverjé Plantation House, which had been serving as the community’s courthouse. In its place was erected a new Moorish-style Algiers Courthouse, with distinctive asymmetrical crenelated towers, as if intended to stand out along the cross-river skyline — the goal of prior riverfront “castles.” It would prove to be the last of its type along the New Orleans riverfront, and the best surviving example today.

What explains the 19th-century appeal of the crenelated castle? The aesthetic reflected a philosophical transformation in Europe, in which artists and philosophers reacted against the lofty ideals of the Enlightenment and the expanding influence of logos by celebrating beauty and embracing pathos. The movement came to be known as Romanticism, and it particularly influenced architects, who abandoned staid Classical Greek and Roman idioms and found inspiration instead in the aging edifices and picturesque ruins of the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

William Alfred Freret designed the Old Louisiana State Capitol in Baton Rouge, perhaps the best surviving example of the castle type. Photo by Richard Campanella.

The Romantics revived Italianate and Gothic styles, among others, and had a special penchant for crumbling castles, which they restored or rebuilt along rivers such as the Rhine. Featured on the Grand Tour taken by aspiring architects, the style spread, and castellated façades became a popular look, especially along riverfronts.

The aesthetic, and the reasoning behind it, faded by the early 1900s, although crenellation continued to appeal to clients and architects seeking to signal stability and commitment. Educational institutions in particular adopted the look, among them the buildings of Loyola University’s Uptown campus, as well as a number of schoolhouses around town.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and the author of “Cityscapes of New Orleans,” “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma” and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements