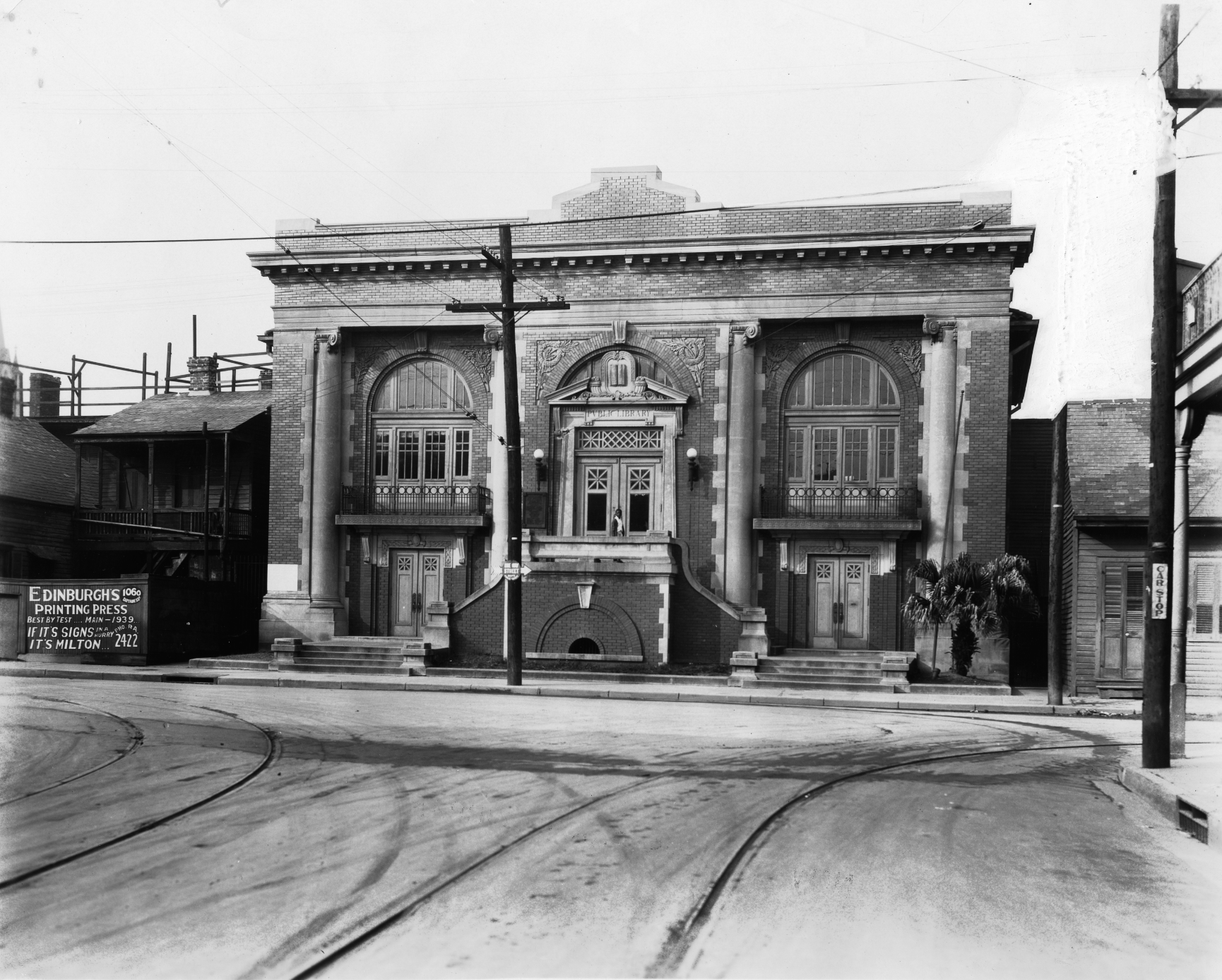

Above image: Gilbert Academy and Gould House photographed in 1949. Photo by William Russel, courtesy of Tulane University’s Hogan Jazz Archive Photography Collection.

This story appeared in the February issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Preservation is a lens focused by the eye of the preservationist. Witness, for example, the far greater efforts to preserve antebellum mansions than slave cabins, or the disparity in the civic resistance to the French Quarter-affecting Riverfront Expressway versus the Tremé-traversing Claiborne Expressway. The preservation movement is now becoming more sensitive to that differential, pointing the viewfinder in new directions and reevaluating the selective focus of the past.

A case in point entails the 1949-1950 effort to preserve the Gould House at 5318 St. Charles Ave., on what had been the campus of Gilbert Academy, now De La Salle High School, and originally New Orleans University.

The Gould House was a raised country villa of the Greek idiom, built probably in the 1850s but possibly as early as 1837, on what had previously been the Ducros and Beale plantations. A man named Samuel Ricker had married into the Beale family, and after much strife among kith and kin, the multiple owners had the merged eight-arpent-wide parcel subdivided in 1849 as Rickerville.

Of the various tracts under development in what was then Jefferson City, Rickerville was perhaps the most rural, known more for cow pastures and truck farms than gardened mansions. The house built for property owner John Gould was the exception. Located riverside of the New Orleans & Carrollton Rail Road (1835; today’s St. Charles Streetcar Line), the stately villa reflected the desirability and higher land values imparted by that new transportation option in this otherwise inaccessible environ. The Gould House did not occupy the center of its large 3.3-acre rectangular block, as might be expected for a country estate, but rather hugged its lower Valmont Street edge, suggesting that while it certainly postdated the railroad, it may have predated the street grid.

Upcoming years would bring epic national transformation: tensions over slavery; secession, war and the defeat of the Confederacy; and in the aftermath, a whole new set of political and social circumstances, particularly for millions of emancipated people. Toward educating the formerly enslaved, a number of old-line Protestant denominations in the Northeast worked with the Freemen’s Bureau in creating schools and universities for African Americans, including in New Orleans.

In 1869, a branch of the Methodist Episcopal Church launched the Union Normal School on Camp and Race streets. Four years later, the trustees expanded the institution into New Orleans University, and in 1884 acquired a spacious lot on St. Charles Avenue for a new campus: the 3.3-acre block of the Gould House, which up to now had pertained to John’s son, Samuel Gould.

Advertisement

The Gould House and its dependencies served as temporary classrooms and offices for the university while architects designed a new Main Building, for which a ground-breaking ceremony was held in 1886. “Rev. M. Dale, the powerful colored preacher of Wesley Chapel,” reported the Daily Picayune on Jan. 24, told the crowd “twenty years ago it was a high misdemeanor to teach the negroes…. Now the ground [is] being broken for a magnificent building in which the colored youth is to be taught. It is a great day.”

Designed by the Chattanooga-based Adams Brothers to teach 400 pupils and board half as many, the four-story Main Building spanned 156 feet in width and 120 feet in depth, and featured “a mansard roof…in the French style of architecture.” Closely nestled dormers and chimneys surrounded the steep-pitched attic, while low pyramidal towers topped the corners and a dazzling octagonal Gothic spire rose from an asymmetrical mount on the front façade. Inside the Main Building were offices, classrooms, an assembly and dining room, a library and a chapel in the rear above the kitchen wing. A museum and dormitories were located upstairs — men on one side, women on the other. Fitted with steam heating and electrical lighting, the building cost more than $50,000.

When completed in 1888, the Main Building of New Orleans University ranked among the most impressive edifices in Uptown New Orleans, and the stately Gould House became the residence of the president.

Designed by the Chattanooga-based Adams Brothers, the four-story Main Building of New Orleans University/Gilbert Academy spanned 156 feet in width and 120 feet in depth. Photo courtesy of the Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, Acc. No. 1979.325.1947

Uptown, all along, had been changing. Streetcar lines had expanded; fields and farms gave way to houses; Tulane and Loyola opened campuses on St. Charles Avenue; Audubon Park got landscaped; and many of the area’s old benevolent institutions, such as orphanages, asylums and hospitals, were getting squeezed out by the higher dollars favoring residential construction. The Touro-Shakespeare Alms House on Daneel Street, for example, relocated to Algiers to make room for new houses, while the Asylum for Destitute Orphan Boys, located just across Valence Street from the campus, moved to an upriver farm — “another evidence of the gradual tendency to remove such institutions from St. Charles Avenue,” the Picayune noted, “where at present they are occupying tracts very valuable indeed as residential sites.”

Another black institution of higher learning, Southern University, departed Magazine Street in 1914 and, after many rejections on account of racial prejudice, finally found a new home in Scotlandville, where Southern is today. The Baptist-founded Leland University, meanwhile, closed on St. Charles Avenue in 1915 and eventually resettled in Baker, after it too encountered racial hostility in its search for a new site.

New Orleans University also departed St. Charles Avenue, though under different circumstances. Philanthropic advisors in the late 1920s recommended that the institution merge with the Congregationalist-founded Straight College, for which a new 70-acre campus had been acquired on Gentilly Boulevard in 1931. This is today’s Dillard University.

As for the now-empty St. Charles Avenue campus, the Methodist Episcopal Church decided to use the complex to house one of the auxiliary preparatory schools of the former New Orleans University, the prestigious Gilbert Academy.

Gilbert’s time on the avenue got off to a rough start. Only four months in, the Main Building caught fire just before Christmas 1935 and suffered $50,000 in damages. Two years later, a fierce windstorm damaged the mansard roof. All along, some white neighbors had worked to get the black students off the avenue. “Efforts had been made,” reported the Times-Picayune on Feb. 21, 1937, “by various interests and by residents in the vicinity to induce the owners to sell.” They succeeded, at least momentarily. A real estate ad in the same issue read, “Gilbert Academy, an old landmark that has been the envy of many prospective land buyers, is offered for sale,” emphasizing in capital letters that it was “IN THE HEART OF THE MOST EXCLUSIVE RESIDENTIAL SECTION OF THE CITY.”

This was an era when real estate interests worked assiduously to segregate neighborhoods through the private contracts, deeds and covenants of their trade. Pressuring a black high school to move out of a wealthy neighborhood aligned with the strategy to keep property values high by keeping selected areas white.

Black leaders met in 1938, according to the New Orleans States, “in an effort to keep Gilbert [on] 5318 St. Charles avenue in operation as a negro Methodist high school.” Others did not mince words. An article in The Negro Star of Wichita, Kansas, reported in 1939 that “every attempt [had been] made to remove New Orleans [University] from the predominantly white neighborhood,” and now that effort targeted Gilbert Academy. “Local whites are again trying to get Negroes off quaint St. Charles Avenue, one of the show places in the exotic town. This time they are working behind the Christian Brothers order, a Catholic Brothers order [with] schools in Lafayette and Covington.”

World War II interrupted the plan, and Gilbert Academy managed to endure another 10 years. Among its alumni were names that would become illustrious locally and beyond, including Ellis Marsalis, Lolis Edward Elie, Ambassador Andrew Young and Thomas Dent.

Advertisement

Finally, in January 1949, the Methodist Episcopal Church closed the academy and sold the property for $312,000 to a real estate firm, which three months later sold it to the Archdiocese of New Orleans. Archbishop Joseph Rummel told the Times-Picayune the land “is to be developed in the immediate future into a Catholic high school for boys residing in the uptown and adjacent sections of our city.” The school would be named St. John Baptist de La Salle, run by the Christian Brothers, who planned to clear away the old buildings for a contemporary complex.

That’s when history buffs took action, in what one organization later described as its “second preservationist attempt,” having recently lost its first battle to save the Olivier Plantation House in Bywater.

But the object of their concern was not the 1888 French Gothic-style Main Building, with its landmark spire, nor Gilbert Academy, with all its social and cultural import. Rather, it was solely the Gould House, the antebellum mansion with the plantation-era visage.

Photo 1: Gould House photographed in 1949. Photo by William Russel, courtesy of Tulane University’s Hogan Jazz Archive Photography Collection.

Photo 2: Gould House photographed in the 1940s. Photo courtesy of the New Orleans Public Library.

A 1980 monograph recalled the organization’s effort to save the Gould House. First, members met with the Christian Brothers to implore them to incorporate the old building into the new school. They declined, but did agree to give the Gould House to any public entity that would pay to move it. Members found willing buyers and funders, and met with the Audubon Park Commission to secure a site. But the requirement was for a public entity, not private parties, and in March 1950, the Commission declined to dedicate land for whomever might move the house. “With no other possible sites in reserve and with the Christian Brothers wanting to begin work on the new school,” wrote the author of the monograph, “the group once again admitted defeat.”

What went unmentioned, both in the 1980 retrospective and apparently in the earlier efforts, was the fate of the 1888 Main Building and of Gilbert Academy. Preservationists’ letters to local newspapers during 1949-1950 expressed concern solely for “the plantation house.” This antebellum building, after all, was older and rarer than its neighbor, and late Victorian buildings, only around 60 years old at the time, were not particularly valued. But in all likelihood, the differing narratives of the two buildings also played a role in which the preservationist lens focused on.

In August 1949, the Carrollton Lumber and Wrecking Company began razing the 1888 edifice, sending its elegant spire crashing to the ground — and its 400,000 bricks to be used as veneer for new houses in Lakeview, itself an all-white neighborhood.

The Times-Picayune saluted the move. “St. Charles ave. is to be congratulated,” it editorialized on July 30, 1949, on the impending demolition of “the ‘old and sprawling home’ of Gilbert academy, taken over now by the Christian Brothers for a modern ‘De La Salle Catholic high school.’ Under the church education program, a high school for negro boys will be built downtown.”

Another editorial later that year joked that “demolition of the 60-year-old old academy building has given the public a magnificent glimpse of what is now offered on a ‘carry away and keep’ basis,” meaning the demolition debris.

One anonymous preservationist, in a Jan. 31, 1950, Times-Picayune editorial, also saw the new view as beneficial, expressing indifference for the black school but reverence for the antebellum mansion: “Now that the adjoining buildings have been torn down, the dignity of this century-old [Gould] house impresses itself daily upon those who pass it.”

In the end, even that argument failed. In April 1950, the Gould House met the same fate as the Main Building. So, too, did Gilbert Academy as an educational institution, as its efforts fell short in raising the quarter-million dollars needed for a new home.

De La Salle High School was dedicated in March 1952, integrated a decade later and went co-ed in 1992. The last structural vestige of New Orleans University and Gilbert Academy was Peck Hall, built in 1911 and razed in 2007, despite the efforts of journalist and preservationist Karen Gadbois to save it by featuring it in her Squandered Heritage series.

From the perspective of circa-1950 preservationists, for whom only the Gould House told stories worth preserving, the episode was a one-account loss. From modern preservationists’ perspectives, there were multiple losses — of a historically significant antebellum home, of a beautiful late-Victorian university building, and of two remarkable educational institutions borne of tumultuous times.

And to be fair, from the perspective of the many good folks of today’s De La Salle High School, who didn’t ask for this past, the episode marks the beginning of their beloved institution, with its noteworthy Modernist architecture.

In 1993, members of the Gilbert Academy Alumni Association erected a historic plaque inscribed with words reflecting their preservationist perspective. It reads:

5318 St. Charles Avenue

The site of Gilbert Academy

and

New Orleans University,

Black educational institutions

Under the auspices of

The Methodist Church

1873 to 1949.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Bourbon Street: A History, Bienville’s Dilemma and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements