This story appeared in the December issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Certain old buildings seem to endure in the collective memory of local history afficionados, while others, despite being of equal or greater prominence, fade from remembrance. Reasons vary. Sometimes it comes down to whether a historic marker had been erected, or whether the structure lasted long enough to be photographed and documented.

In other cases, it mattered whether the building (or story, or explanation, or colorful historical figure) had been published in the many popular narrative histories or “local color” literature of the late 1800s and 1900s, thus giving them a much wider readership, influencing even Internet coverage today. That’s what brought lasting fame to buildings like Madam John’s Legacy, Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop, the Girod (Napoleon) House and the LaLaurie Mansion.

Then there is the factor of intentional amnesia, particularly of landmarks associated with slavery and racial violence, and its antithesis, namely the emphatic valorization of anything associated with the Confederacy. Both phenomena are now undergoing purposeful reversals.

Other “memory differentials” are harder to explain. Why is there so much more written about the Seven Oaks Plantation House in Westwego than its downriver counterpart, the Belle Chasse Plantation House? Why is the Old French Opera House so much more remembered than its equally influential uptown counterpart, the American Theater? I’ve long been confounded as to why so few people know about the Ossorno House on Gov. Nicholls Street, a 1780s Creole residence originally built as a rural Bayou St. John plantation — highly unusual for a French Quarter structure.

Which brings us to Harvey Castle (or Harvey’s Castle), which strikes me as surprisingly well-remembered, despite that it was razed over a century ago at a site on the West Bank of Jefferson Parish, far from the renowned historic neighborhoods of New Orleans proper. Why? Perhaps for its sheer distinction — its whimsy, its folly, its visible salience — or for that all-important historical marker, which stands today on Destrehan Avenue at Fourth Street in Harvey.

Yet, like even the most famous of local historic structures, the details of Harvey Castle are less known, and worth recounting.

Advertisement

Harvey Castle was built in 1846 along the Destrehan Canal, today’s Harvey Canal, and although it was designed as a residential mansion, the structure was used just as much as an office for canal operations, making it vital to the economic development of what is now Harvey. That waterway was the brainchild of Nicholas Noel Destrehan, a maverick landholder and entrepreneur who, in the late 1830s, had one eye on the abundant natural resources of the Barataria Basin to his south, and the other on his neighbors to the west, who were tapping into that largesse via the Company Canal in modern-day Westwego.

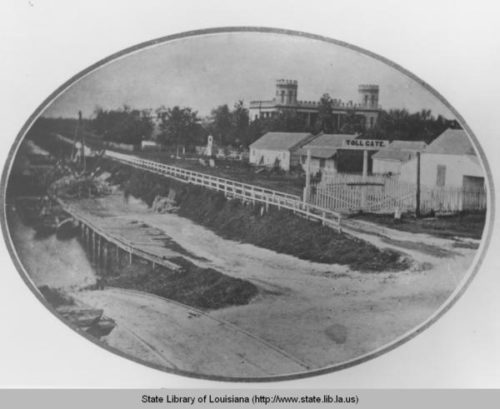

In 1839, Destrehan decided to hire a team of Irish “ditchers” to excavate his own channel to connect with Bayou Barataria and points south. Completed by 1844, Destrehan’s canal soon became busy with barges, luggers and schooners hauling timber, moss, finfish, shellfish and game in from swamps, marshes and bays. In short time, Destrehan earned a fortune by charging tolls for vessels to sail there from the Mississippi River via a “marine railway” he designed to get over the levee, a lock being too risky.

Keen in commerce and a tad eccentric, Destrehan had all along been working on a “castle” for his canal-side plantation. He called it the Louisiana Lyceum and Museum, for his collection of art and curios, although snickering neighbors were more inclined to call the five-story edifice “Destrehan’s Folly.”

Equally keen was Destrehan’s daughter Louise, who was born in 1827 and raised steeped in the Catholic French Creole culture of the rural West Bank (known as the Right Bank at the time). In 1845, Louise married a Scotts-Irish adventurer from what is now West Virginia by the name of Joseph Hale Harvey, who her father had approved as worthy of his daughter as well as the future helmsman of the family empire.

After twin wedding ceremonies — one Protestant, one Catholic — and a year-long international honeymoon, Joseph and Louise Harvey returned home and got started building a house befitting the West Bank’s newest power couple. Thus arose Harvey Castle.

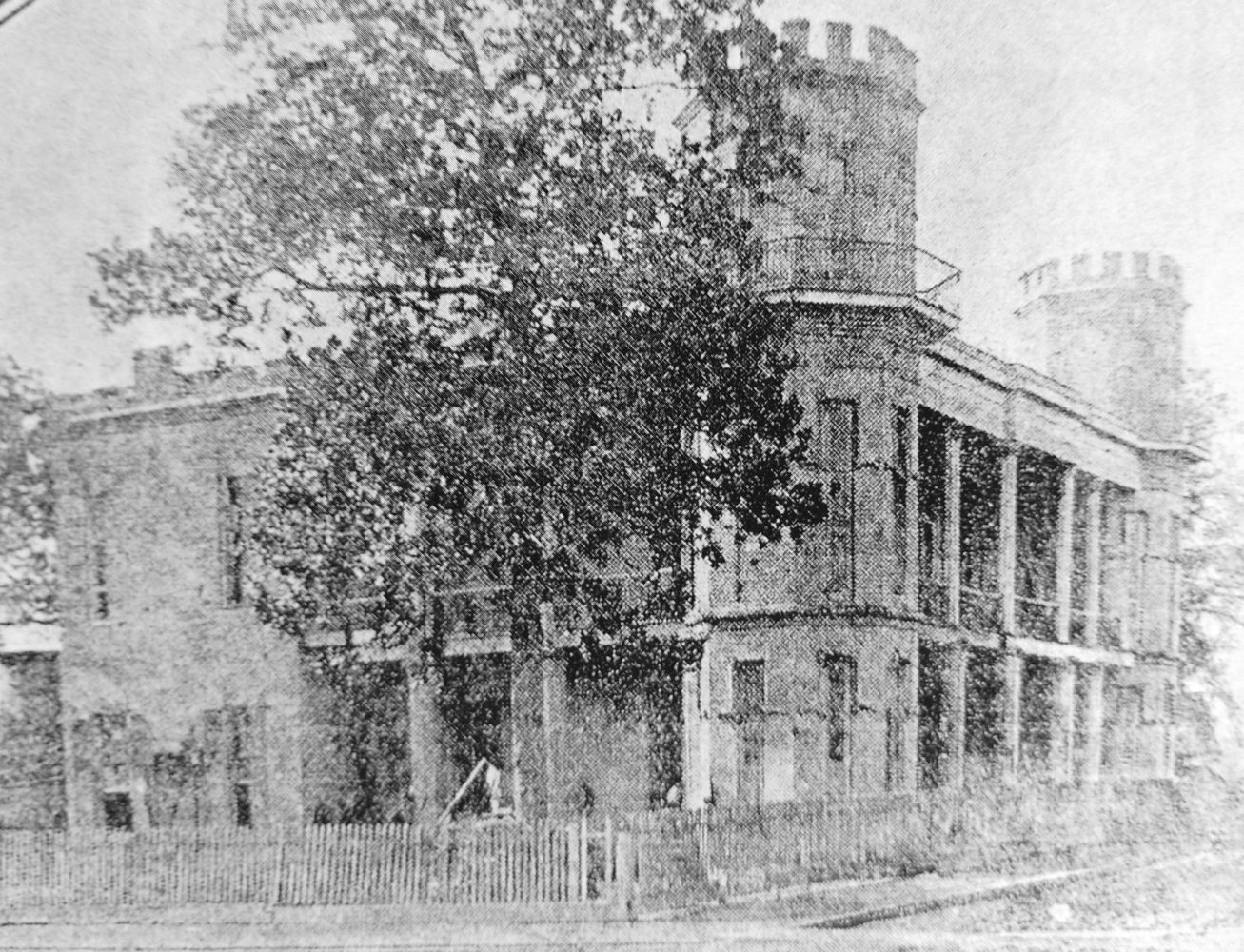

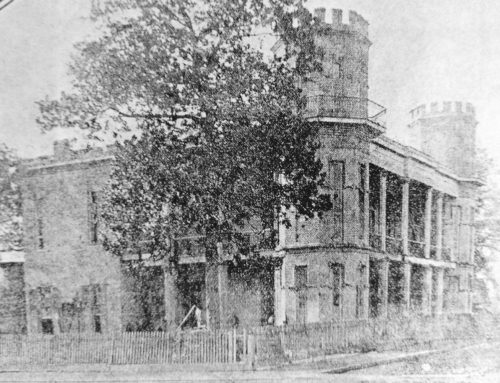

Photo 1: A photograph of Harvey Castle. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. Photo 2: The Harvey Castle, Marine Railway and Toll Gate of the Harvey Canal. Image courtesy of the State Library of Louisiana.

A family descendant described the manse as a “medieval, two turreted baronial castle patterned from a faded old picture of [Joseph’s] grandfather’s and great uncle’s home in Scotland.” Inside the three-story edifice were walnut-finished walls, marble mantels imported from Italy, 18-foot-high ceilings and two grand staircases. Outside were ornamental gardens with various flowering plants, fruits, vegetables, shade trees and walkways, which together with the house spanned roughly a full city block about 300 feet from the river.

Building materials came from local sources. “The brick was a product of the town of Harvey,” wrote the New Orleans States years later, “as was the cement, which was made of oyster shells and river sand.” Harvey Castle was built by free men of color “living in what was then ‘Free Town,’ now McDonoghville[;] be it said to the credit of these men and their skill and industry.”

According to historian William D. Reeves, Harvey Castle was a Victorian Gothic answer to the elder Destrehan’s own live-in art museum, that five-story “vaguely Palladian” folly that remained unfinished when it burned to the ground in 1852. Its demise left Harvey Castle as the premier landmark in the vicinity, visible for miles across the river. Inside, Joseph and Louise raised their growing family, and oversaw their multi-use plantation, the economic lynchpin of which was the now-renamed Harvey Canal.

Why build a plantation house to look like a castle? Some surmised a connection to Joseph Harvey’s ancestral home in Scotland. Others suggested it reflected Harvey’s years as a Mississippi riverman, where he would have seen how the elaborate adornment on steamboats had inspired comparable detailing on some plantation houses (witness the “steamboat gothic” style of the San Francisco Plantation House in Garyville).

As for the Destrehan side of the family, the taste may have betrayed a provincial yearning to showcase its claims to an aristocratic French lineage. Commented a tutor who lived with the Destrehans the same year Harvey Castle was constructed, “As had long been the custom here with Creole families of sufficient means, the sons…were sent back to the home of their ancestry to receive a more systematic and thorough training. Mr. Destrehan thus in early years imbibed tastes and ideas in La Belle France, [including] an architectural taste, and a wish to reproduce here some of the old baronial structures of that land.”

Advertisement

There may have been broader design fashions at play, as the “castle look” was popular in the Romanticist-inspired architecture of this era, particularly for riverfront buildings. The U.S. Marine Hospital, built in McDonoghville starting in 1834, sported Gothic towers and battlements, as did the twin Belleville Iron Works in Algiers, which had citadel-like turrets.

As for Louise, she focused on running the family enterprise as well as raising her family under the crenelated towers of Harvey Castle. After her father’s death in 1848, Louise, now 21, became proprietor of the canal (along with 26,000 acres of Joseph’s inherited Virginia land), and co-owner of a community estate that included 76 enslaved people inherited from her father. Louise Destrehan Harvey ranked among the wealthiest and most powerful women in greater New Orleans in this era, and her empire rested largely on enslaved people — and that waterway to Barataria riches.

Harvey Castle was a silent witness to each subsequent phase of West Bank history. It saw the arrival of the railroad and a drawbridge in the 1850s; occupying Union troops in the 1860s; the postbellum transformation of enslaved plantations to leased truck farms; cattle drives from Texas and the rise of riverfront industry; and attempt after frustrating attempt to build a suitable river lock for the Harvey Canal.

In 1874, when the Jefferson Parish seat of Carrollton was annexed into the City of New Orleans and a need arose for a new parish courthouse, Louise Destrehan Harvey decided to lease Harvey Castle for that purpose. In April 1874, the “Police Jury of Jefferson, Right Bank” took occupancy in Harvey Castle, despite that it lacked legal authority to pay rent for it.

After three years of waiting, Louise filed suit for the $3,400 owed to her. But judges ruled against her, even as she allowed the Police Jury to stay while trying to persuade the jurors to purchase the property. She finally evicted them in 1884 — the queen of the castle ejecting a freeloader government. Homeless again, the Police Jury eventually settled into William Tell Hall, still standing on Newton and Third streets in Gretna. Jefferson Parish government remains in Old Gretna to this day.

In 1898, at age 71, Louise made a key decision to incorporate The Harvey Canal Land and Improvement Company. She arranged to keep control within the family, and installed her son Horace as manager. Horace Harvey endeavored to bring the operation into the 20th century, and that meant a renewed effort to build a modern lock. Between 1902 and 1907, after numerous travails including the death of Louise at age 77, engineers finally succeeded in completing a strong new lock where the Harvey Canal adjourned the Mississippi River.

Advertisement

That success led to the demise of Harvey Castle. As the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers pieced together a public barge canal stretching along the Gulf Coast from Texas to Florida, it contemplated how to bring this new national asset through the Port of New Orleans. After a years-long competition with the Company Canal in Westwego, government authorities decided in 1919 to select the Harvey Canal for their project, which became today’s Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW).

While the government would now own the actual channel of the Harvey Canal, the Harvey Canal Land and Improvement Company would retain control of all wharves and canal-side facilities, now positioned to boom with oil-related economic activity. It also still owned Harvey Castle, which it leased to tenants.

But the impending boom did not bode well for the aging citadel. Corps engineers, upon taking control of the channel in 1924, promptly set about updating the facilities and widening the channel. The aging mansion stood in the way, and the solution was an expedient one. “Harvey Castle, Across the River…To Be Demolished,’ reported the New Orleans States on May 18, 1924. It was gone by year’s end. A decade later, the Corps spent $2 million to replace Horace Harvey’s lock with a new 425-foot-long, 75-foot-wide, 12-foot-deep lock.

Today, 300 feet from the interior gate of that same lock, stands a historical market at the intersection of Highway 18 and Destrehan Avenue. “HARVEY CASTLE SITE,” it reads, “Gothic Revival home of Marie Louise Destrehan and her husband Joseph Hale Harvey[;] it served as the third courthouse of Jefferson Parish, 1874-84. Located east side of Destrehan Avenue 450 north of railroad. Demolished 1924 to enlarge Harvey Canal and Locks.”

That marker, the endurance of the Harvey Canal as part of the GIWW, the sheer oddity and salience of Harvey Castle, has kept its fame alive to this day. “Known from one end of the Mississippi River to the other,” wrote the States newspaper of Harvey Castle in 1925, the mansion served river pilots who “took their bearings from its lofty turrets” as they steered around the great crescent.

The organization founded by its original occupant, the Harvey Canal Limited Partnership, retains control of the waterway’s bankside land to this day, and is controlled entirely by the descendants of the Destrehans and the Harveys. The company’s logo, which appears on its letterhead and website, features the distinctive profile of Harvey Castle.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; Cityscapes of New Orleans; Bourbon Street: A History; and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements