This story appeared in the October issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

On the 900 and 1000 blocks of Canal Street, a project by Redmellon Restoration & Development is underway to turn the lights back on in the upper floors of five historic buildings: four adjacent buildings between 1001 and 1015 Canal St., and one across the street at 934 Canal. Today, four of the five buildings have retail tenants on the ground floor, but the upper floors have remained empty for decades.

As business carries on along the ground floor, work will soon commence to transform the upper floors into a hotel.

Redmellon, a local real estate development company focused on historic rehabilitation, urban infill and affordable housing projects, is a co-owner of this Canal Street project, along with building owner Hammy Halum. (Full disclosure: Neal Morris, principal of Redmellon, is a board member of the Preservation Resource Center.)

The five buildings were constructed at different times and weave different architecture and history into the urban fabric of the streetscape.

“These old buildings aren’t just important because the bricks are old,” Morris said. “What’s important is this tie to the past, and the tie to real people’s lives. The buildings become a way to look at the stories of the New Orleanians who lived there.”

Taking the stairs from the modern-day retail spaces up to the buildings’ upper floors today is like walking into a time capsule. Many of the spaces remaining largely untouched since they were vacated decades ago. Artifacts and antique machinery from previous retail heydays — including piles of old mannequins, cash registers and store signs — are still scattered throughout the upper floors.

Redmellon brought in Melissa Chua, a videographer, to help research, document and highlight the important moments, people and uses of the buildings. Historian Hilary Irvin also researched the buildings’ histories for the project’s historic rehabilitation tax credit applications.

Advertisement

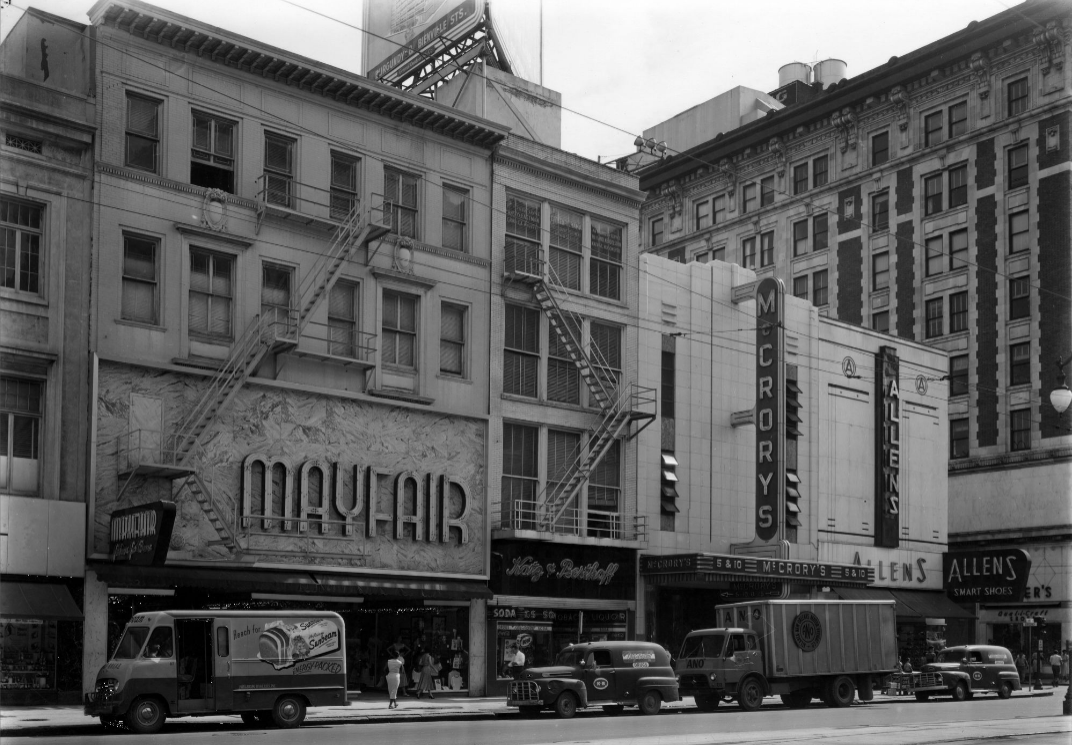

Photo courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection Charles L. Franck/ Franck-Bertacci Photographers Collection.

Of the five buildings in this project, the three-story masonry structure at 1001 Canal, at the corner of Canal and Burgundy streets, retains the most of its historic building fabric. Built in the 1870s, the building’s current appearance dates to an 1880s remodel by Junius Hart, who owned and operated a piano store and concert hall in the upper floors. In the early 20th century, the space became a “taxi-dance hall,” a jazz and dance venue where male patrons could pay five cents to dance with women who were employed as dancers. Although deteriorated from decades of abandonment, an ornate plaster frieze depicting dancing maidens still surrounds the room where the taxi-dance hall was once located on the second floor. The building’s facade was covered by a modernist sheath in the 1930s, which was removed in the early 2000s to reveal the 19th-century facade.

Of the five buildings in this project, the three-story masonry structure at 1001 Canal, at the corner of Canal and Burgundy streets, retains the most of its historic building fabric. Built in the 1870s, the building’s current appearance dates to an 1880s remodel by Junius Hart, who owned and operated a piano store and concert hall in the upper floors. In the early 20th century, the space became a “taxi-dance hall,” a jazz and dance venue where male patrons could pay five cents to dance with women who were employed as dancers. Although deteriorated from decades of abandonment, an ornate plaster frieze depicting dancing maidens still surrounds the room where the taxi-dance hall was once located on the second floor. The building’s facade was covered by a modernist sheath in the 1930s, which was removed in the early 2000s to reveal the 19th-century facade.

Photos courtesy of Redmellon

The three-story building at 1005 Canal was built circa 1900, and its current Art Deco appearance dates to an extensive 1930s remodel for the McCrory’s five-and-dime store. In 1960, this McCrory’s was the site of a lunch counter sit-in during the Civil Rights movement. After an initial sit-in organized by the Congress of Racial Equality at the Woolworth’s at 1039 Canal St. (that building has since been demolished), four students — Rudy Lombard, Oretha Castle, Cecil Carter, Jr. and Sydney Goldfinch, Jr. — sat down at McCrory’s segregated whites-only lunch counter and asked to be served together. The group was arrested, and an appeal of their convictions went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in Lombard v. Louisiana. The court’s decision overturned the arrests and was a major victory for the Civil Rights movement. The building’s Art Deco facade remains intact, but many of its interior features have been lost or modified over the years.

Photo 1 courtesy of Redmellon. Photo 2: McCrory’s lunch counter demonstration on March 12, 1961. Photo by Charles F. Bennett, The Times-Picayune archive.

Built in 1904 after a previous structure was destroyed by a fire, this building was given its current facade during a 1917 remodel after receiving damage from another fire. Over the years, its four floors held a multitude of commercial tenants, including an umbrella manufacturer, a photography studio, the Singer Sewing Machine Company, several drug stores, including a Katz & Besthoff during the 1930s and 1940s, and Burt’s Shoe World.

Photos 1-3 courtesy of Redmellon. Advertisement from The New Orleans Item, Sept. 17, 1939, via NewsBank.

Advertisement

This four-story building was constructed in 1915 after a fire destroyed the previous building on its site. Constructed out of concrete and brick to be fire-proof, the exterior retains its original neoclassical details, including dentils and cartouches, but most of its current interiors mainly date from the 1950s to the 1980s, when the Mayfair department store occupied the building. Prior to Mayfair, the building was home to a Noah’s Ark furniture store and a Burt’s Shoe Store, with the upper floors used as offices and studios.

Photos 1-3 courtesy of Redmellon. Advertisement from The New Orleans Item, Feb. 2, 1940 via NewsBank.

While the four buildings on the 1000 block of Canal are all adjacent to each other and separated by party walls, 934 Canal is located across the street from the rest of this development project. Located in the middle of the 900 block, this concrete, brick and stucco building designed by architecture firm Favrot and Livaudais also employs a fire-proof design. The building was a flagship store and offices for the Singer Sewing Machine Company, which also held sewing classes and community events in the space. The interiors were remodeled in 1974 for a McDonald’s on the ground floor, and the upper floors vacated.

Photos 1-3 courtesy of Redmellon. Photo 4 courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Charles L. Franck / Franck-Bertacci Photographers Collection.

Responding to modern-day life and safety codes without losing first-floor retail space has been a major challenge for the redevelopment of the upper floors of buildings all along Canal Street and a key factor in their prolonged vacancy. For this project, Redmellon tapped Trapolin-Peer Architects to design creative solutions for the sites while preserving their historic elements.

Modern codes require two means of egress from the buildings’ upper floors. These historic commercial structures were designed with long, narrow plans and dividing party walls. Trying to insert two new sets of stairs into each individual building and adding corridors to the exterior would reduce a substantial amount of first-floor retail space.

But “once you connect the buildings together on the upper floors, those two means of egress are spread out across the buildings, and there’s less disruption to the ground-floor retail tenants,” said Ashley King, senior associate at Trapolin-Peer Architects and the project architect for the redevelopment. (Full disclosure: King is a board member of the Preservation Resource Center.)

“The other challenge is providing light and air to the center of the building at the upper floors,” King said. “Most of them were originally storage or office spaces, so the need for a great deal of natural light wasn’t as great a concern” when they were originally built.

To bring light and air into the new hotel units, two lightwells will be carved out of the middle of the four buildings on the 1000 block, providing new courtyard-like spaces within the interior. A similar strategy was used by Trapolin-Peer in the rehabilitation of the historic May & Ellis building on Chartres Street in the French Quarter. Exterior catwalks through the lightwells will connect the buildings. A series of ramps through the corridors and catwalks will account for differences in floor heights between the buildings, and will provide accessibility while making the space operator-friendly for housekeeping carts and travelers with luggage.

A third lightwell is planned across the street at 934 Canal. A common alley is located behind this block, and is the only common alley still in existence on this section of Canal Street. “We’re able to develop this small narrow building with minimal impact to the ground floor, because we’re able to take one stair out to the street level and the other stair is able to go out to the alley,” King said.

The addition of a fifth floor is planned for 1011, 1015 and 934 Canal, with a set back from the Canal Street facade to ensure minimal visibility from the street level. On the ground levels, the commercial tenants in the four buildings on the 1000 block of Canal will remain in place while work takes place on the upper floors. Stairwells, a small hotel lobby area, bathrooms and utility spaces will be carved out of the back-of-house areas on the first floor. The ground-level space at 934 Canal, a vacant former McDonald’s, will receive a “white box” renovation and be prepped for a future restaurant tenant.

Advertisement

In addition to the new updates and a number of structural repairs, many of the buildings’ historic elements will be restored. An ornate plaster frieze at 1001 Canal will be repaired, with molds taken of the existing portions to patch places where pieces have fallen off or been removed. The hotel rooms planned for that space will be set in a pod in the middle of a former dance hall to maintain the frieze that wraps around the perimeter as well as the decorative arches that once separated the dance hall from a piano repair shop.

Other interior details, including beadboard walls and ceilings, moldings and cast-iron columns, will be preserved or replicated in-kind where missing or damaged. Windows along the Burgundy Street elevation that were walled over in the mid-20th century will be reconstructed.

“Once we can get in there and do some more selective demolition, we’re going to find some fun surprises,” King said. “I can’t wait to start to peel back those walls and start to see the ghosts of the past, and the remnants of previous inhabitants.”

After the selective demolition peels back the building’s many layers of history, architects “plan on taking a good look through the building and retaining the patina and the history,” King said. “It’s such an interesting and important part of a building’s story — not just freezing it in time, and a pretty pristine picture, but how people lived, inhabited and worked in those spaces.”

The project will be made possible with historic rehabilitation tax credits. The building at 1005 Canal, however, isn’t listed on the National Register of Historic Places, which would prevent the use of historic tax credits for its rehabilitation. The other buildings on the 1000 block of Canal are contributing structures in the Vieux Carré National Register Historic District, which has a period of significance from 1745 to 1933. Since 1005 Canal was significantly altered after 1933, when it received its current Art Deco appearance, it was not deemed a contributing structure when the district was nominated. The team is working to get the building individually listed on the National Register, which would commemorate its important connection to the Civil Rights movement and make the building’s rehabilitation eligible for historic rehabilitation tax credits.

Trapolin-Peer Architects is working with Irvin as a tax credit consultant, and will be working with Palmisano as the contractor for the project as well as Woodward Engineering Group and Salas O’Brien as engineering consultants. Work is scheduled to begin in the spring with an anticipated completion date of summer 2021.

As construction unfolds, the challenges of the project and its practical design solutions will be documented and shared online and through social media channels. Named the Preservation Toolkit, the series of photos and videos will be a public resource for people to learn about the project and the buildings’ storied histories. “This is a way as civic-minded individuals that we can increase the social impact of our work,” Morris said.

“It’s a tough undertaking to take what we’re doing right now and make it a reality. If we can open up the process and make it more friendly, then other developers, architects, city planners and cities are going to be more likely to encourage this type of process because it is important,” said Chua, who is working on outreach, videography and social media for the project. “This is just a really neat way that we can advocate for preservation.”

Davis “Dee” Allen is PRC’s Communications Associate and a staff writer for Preservation in Print.

Advertisements