This story appeared in the June/July issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

I’m a Preservationist

I’m a Preservationist

Mel Buchanan

RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts and Design, New Orleans Museum of Art

Buchanan was recently named to the Committee for the Preservation of the White House, an advisory committee comprised of experts in historic preservation, architecture and decorative arts.

Tell us about your role as the RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts and Design at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

At NOMA, where I’ve been Curator of Decorative Arts since 2013, my job is to develop exhibitions, guide acquisitions, and manage research for a collection that covers a wide range of objects from ancient Roman glass to conceptual aluminum chairs made this year.

Traditionally, the role of curator was more about sharing “expertise” in a content area — say Asian art, or European sculpture, or photography — but today’s museum curators generally work much differently than that old connoisseurship model. We present our research and knowledge, but we also act as project managers for exhibitions and publications, build local and national networks of collaborators, and lean more into the work of “asking questions,” bringing in a broad collection of perspectives to how we understand the museum’s collection.

How do you think your museum experience will contribute to your new role on the White House Committee?

Well, in my first meeting last month at the White House, after I overcame my nerves, I did what I do in meetings here: Ask questions! The museum field at large — and this would include the White House — is engaged in introspection about how our profession has been conducted historically, and how we must evolve into the future. For policies guiding art collections, museums are looking at how to address glaring historic gaps in who was represented in institutional collecting. And for ongoing preservation work, the project of replacing a curtain in a historic interior might involve paying as much attention to the conditions of how something is produced as has always been paid to the specific selections of things like material texture and color. To be clear, my service on the Committee for the Preservation of the White House has just begun, but these are just a few ideas I am thinking about as we begin our advisory work.

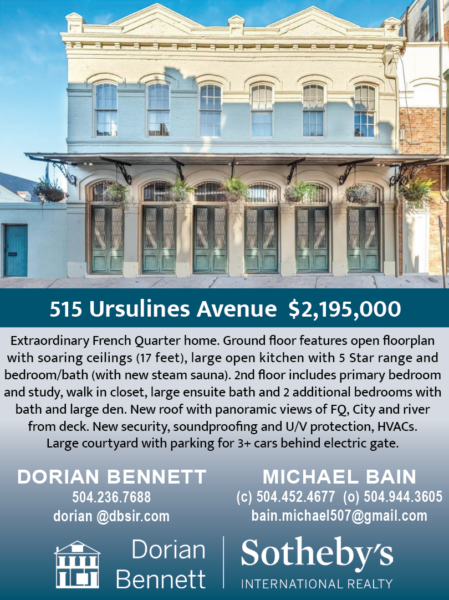

Advertisement

How has your work at the museum evolved to address these field-wide changes that you’ve mentioned?

There are many different ways that we’ve been working at NOMA to ensure that our collections and exhibitions tell as broad of a story as possible. In the decorative arts collection, we have focused on commissioning contemporary artists to respond to traditional objects in our collection. For example, the Houston-based designer Joyce Lin brings concerns about the environment and conceptual ideas about artifice to looking at 19th-century Louisiana ladderback chairs, and the ceramicist Roberto Lugo makes a contemporary, updated version of 19th-century French porcelain honoring Louis Armstrong and Lil’ Wayne. Art has a way of showing something more poignantly than words on a label.

Can you give us a preview of any upcoming exhibitions you’re working on now at NOMA?

Opening this summer, NOMA will host a really extraordinary exhibition on the complexity of the United States’ fashion history — Fashioning America: Grit to Glamour, opening July 21 and on view through November 26. Kicking off with a tasseled New Orleans late-19th century ball gown and a metallic suit worn by Big Freedia to the Miss Universe pageant earlier this year, the presentation weaves together fashion then and now, and juxtaposes iconic brands (Nike shoes and Levi jeans) with new stories celebrating the long contributions of Indigenous, Black, immigrant and women designers to American fashion. Working with the show’s original creators, curator Michelle Tolini Finamore and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, we are engaged with all the pragmatic details for New Orleans — mannequins and A/V components — but also bringing in some additional works of art that engage with fashion in this city.

Further afield, I am working on a 2024 exhibition and catalogue that shares NOMA’s glass collection. We will highlight the more than 5,000 objects — from Egyptian core-formed makeup bottles to sleek 1980s glass chairs and contemporary art chandeliers — comprising one of the nation’s finest collections of glass through themes such as craft, stylistic exchange, technology, foodways and identity.

What does preservation mean to you?

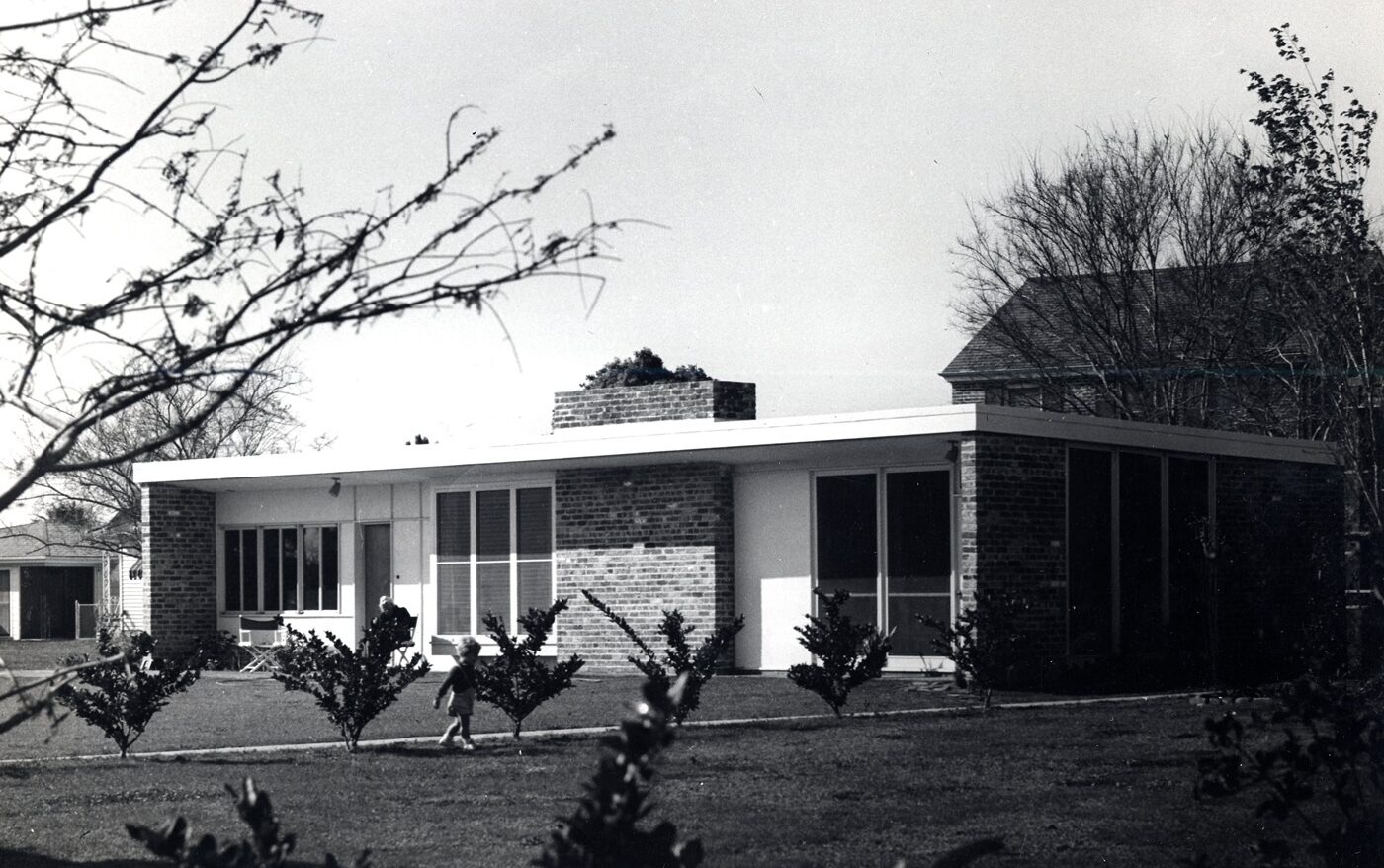

When I look back at how I was first taught to think about architecture, objects and landscapes — this would be in the late 1990s into the 2000s — we were taught to start with materials first. The actual physical brick or teapot could be the guide to understanding history’s complexity. At the time, that approach to material culture was somewhat radical, and we thought it progressive in prioritizing makers and users (who were more diverse in terms of economics, race, gender, nationality) over history’s traditional written texts.

However, I’ve softened that “object first” understanding, as I’ve seen that it can tend to prioritize a brick or a teapot over the human experience. In my work at the museum, or as I would imagine all types of preservation work, I try to remind myself that the physical object is not itself the priority, but is in service of the human stories, ideas, and sentiments that it passes along from past to present.

noma.org • facebook.com/NOMA1910 • @neworleansmuseumofart

Advertisements