This story appeared in the March issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

I’m a Preservationist

I’m a Preservationist

Dr. F. Brobson Lutz, Jr.

Internal Medicine and Infectious Disease Physican

You bought Tennessee Williams’ home in 1981, and there was a stipulation in the sale that the playwright could keep his apartment in the building for $100 per month until his death. What was it like being the famous writer’s landlord, and what do you love about the property?

Kenneth Combs and I live at 1022 Dumaine St., a townhouse restored by Ernestine and Alan Rinehart in 1959. The back story: Alan was the son of another literary giant, Mary Louise Reinhart, and Alan and Ernestine’s daughter was Jaye Dobbs Percy, a relative of Walker Percy, another famous writer.

Our home is two doors down from where Tennessee Williams lived. His house, accessory buildings and courtyards comprise a huge hunk of the block. The property takes a turn at the rear and opens up into an interior courtyard forming what folks down here call a key lot. Thus, we shared a common fence with the back courtyard owned by Tennessee Williams.

One Sunday morning in 1981, a few weeks after we bought 1022 Dumaine, we heard some moans and groans coming from next door. We peered over our courtyard wall and saw a large kidney-shaped swimming pool ringed by a dozen or so young men in various states of dress and consciousness. We had witnessed the aftermath of a Quaalude and amphetamine punch party that Tennessee Williams had held.

Maintaining property in the French Quarter is a challenge. Williams told us that a fleece job by “a bunch of Russian house painters” was the final straw, but it saddened him to leave the second-floor apartment that he loved so dearly. We jumped in with an offer. Ken Combs and I offered to buy the property with an agreement that Williams could keep his second-floor balcony apartment for $100 a month. I think that offer sealed the deal, and we became the proud owners of what Williams called his “spiritual home.”

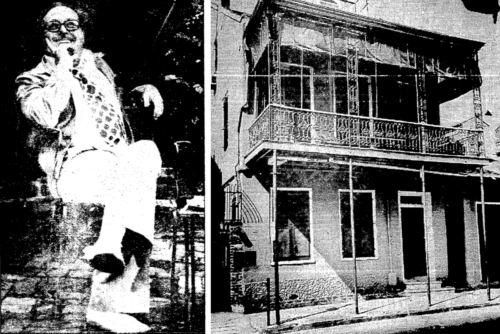

Left: Tennessee Williams in the courtyard of 1014 Dumaine St. Image from The Times-Picayune, February 26, 1983.

Left: Tennessee Williams in the courtyard of 1014 Dumaine St. Image from The Times-Picayune, February 26, 1983.

Right: 1014 Dumaine St., circa 1976. Image from The Times-Picayune May 9, 1976.

Advertisement

What made you want to live in the French Quarter when you first moved to New Orleans?

The smells comingled with friendly folks and old architecture. My first visit was in 1965 between high school and college. As an 18-year-old from a dry county in North Alabama, the sights, sounds, huskers and especially the aromas and other olfactory delights of Bourbon Street sealed the deal. I am one of those folks who knew within 15 minutes on this soupy soil that this is where I belong.

After two years at Auburn and then two more interesting years at Vanderbilt, I moved to New Orleans to begin medical school at Tulane. I have lived in the French Quarter ever since. As a student, I rented apartments from a series of older women who formed the backbone of the residential Quarter. The nice ones included Harriet Riley on Orleans, Dixie and Irma Fasnacht on Bourbon, and May Godchaux on Dumaine. Marjorie Waterman on Burgundy was another.

How has the residential side of the French Quarter changed over the years that you’ve lived there? What is the biggest issue faced by residents there today?

As for full-time people living here, the French Quarter has become a residential desert. The buildings with rental apartments owned by live-in or nearby owners, which housed my friends and acquaintances in the 1970s, are now condos with absentee owners. Real estate sales-fueled conversions permanently tattered the once marvelous and unique population tapestry of the Quarter I knew as a medical student.

Before his recent death, photographer Louis Sahuc told me that he was one of only two full-time occupants in the Upper Pontalba. Rarely do I see a light from an apartment in the Lower Pontalba. The second floors and above bordering our city’s most historically significant square have become nothing more than a pieds-à-terre for the rich and politically connected. We need full-time residents to keep the quarter vibrant.

We have the Vieux Carre Commission and its volunteer commissioners who are charged with saving and guarding the architectural fabric of the Quarter. If one of those sharp-eyed inspectors sees a few fronds of maidenhair fern purifying the air from a third-floor roof, you can get a $3,000 fine.

You’re well known for your love of the New Orleans restaurant scene. What are your favorite places to eat these days?

Galatoire’s remains my favorite restaurant, but it is no longer the Creole powerhouse it once was. Antoine’s is the go-to place for special occasions. Crescent City Steakhouse, one of two steakhouses in town known to me that still use a bone saw, is a favorite. For both raw and cooked oysters, Pascal’s Manale, and Casamento’s are favorites. The oyster bars on Iberville are still shucking nice oysters, but they shuck right out of the cooler, and you no longer encounter banks of iced-down bivalves. For other seafood, GW Fins and Drago’s lead my list.

Advertisement

What does historic preservation mean to you?

To me, preservation of historic buildings is important, but even more important is preserving the fabric, diversity, and lifestyle of the people who live within a historic district. We need a vibrant French Quarter, not one under glass with no ferns in the masonry.

View from the front balcony and courtyard of the apartment in 1014 Dumaine St. where Tennessee Williams once lived. Photos by Liz Jurey

Advertisements