This story appeared in the February issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

After the Indian Removal Act in 1830, thousands of Native Americans were displaced from their ancestral homelands and forced to relocate to territories further west. The inland journey known as the “Trail of Tears” would become a well-known, painful chapter in American history.

A somewhat lesser-known route over water also brought thousands of Native Americans by boat to New Orleans’ Jackson Barracks and Fort Pike, where they would be detained before continuing up the Mississippi River on steamboats and finishing the journey over land. The voyage was treacherous, and many Native people died along the way.

Physical reminders of this history had been buried for years, until the recent discovery of a Seminole woman’s remains at Jackson Barracks spurred further archeological studies and an extensive consultation process. Now, a new memorial green space at the site commemorates its history and honors the Native Americans, soldiers, enslaved people and civilians who lived, worked and died there.

Brian Thomas Palmer, assistant chief of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, spoke at the dedication ceremony for the memorial green space in November 2021. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana National Guard.

Brian Thomas Palmer, assistant chief of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, spoke at the dedication ceremony for the memorial green space in November 2021. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana National Guard.

Jackson Barracks was built on the banks of the Mississippi River to defend the City of New Orleans and has continuously been home to a local military presence since its construction in the 1830s. The site is home to the Louisiana National Guard, and its antebellum buildings are still used as officers’ quarters today.

The post was originally called “New Orleans Barracks,” but was renamed in 1866 to bear the name of Andrew Jackson, who was commander in chief during its construction. During his presidency, Jackson also signed the Indian Removal Act into law, which forced Native Americans from their homelands and brought many of them through the barracks site before they continued their journey westward.

The barracks’ new memorial, which acknowledges the site’s role in the forced relocation, was dedicated in November, but the project had been years in the making. In early 2005, construction workers digging under an administration building discovered the remains of two people — a Seminole woman, identified by beaded necklaces and silver jewelry, and an unidentified man — and realized they had unearthed the barracks’ original cemetery. The burial grounds had been used for military personnel and civilians from the 1830s until the opening in 1864 of nearby Chalmette National Cemetery, where most of the military burials at Jackson Barracks were reinterred. Those who remained at the barracks’ cemetery were eventually forgotten to time due to unmarked graves and a lack of records, and new buildings were constructed on top of the gravesites in the 20th century.

Months after the accidental discovery, Hurricane Katrina inundated the site with more than 10 feet of flood water. The building that sat on top of the former cemetery — in addition to many other non-historic buildings damaged by the flood — was later demolished, and further archeological research uncovered additional remains from the cemetery.

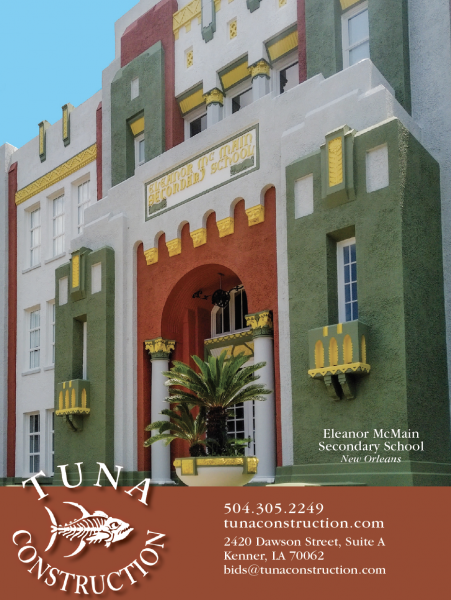

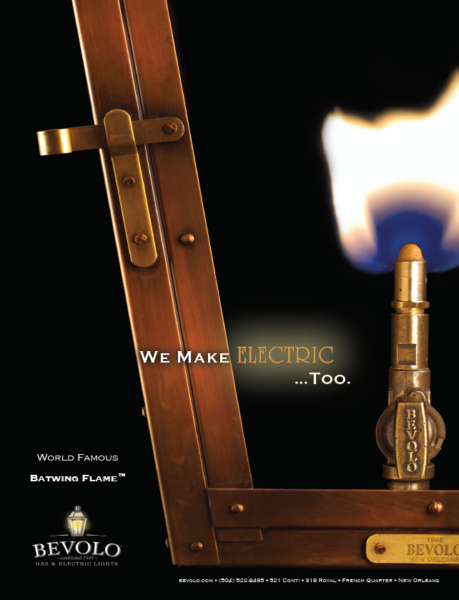

Advertisement

Through compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, many representatives came to the table to weigh in on the site’s future. (Section 106 requires federal agencies to consider a project’s potential effect on historic properties. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act is a federal law that provides for the repatriation and disposition of certain Native American human remains and objects of cultural significance.) The parties involved during these processes included the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, the Louisiana State Historic Preservation Office, several federally recognized tribes, multiple state agencies, local preservation groups — including the Preservation Resource Center — and many others.

After thorough archeological investigation and the demolition of flood-damaged buildings, the group reached an agreement to leave the burial ground undisturbed and establish a memorial green space with interpretive historic markers to commemorate the people buried on the site.

“The most gratifying thing was to have so many people from so many different backgrounds, with so many different things that were important to them, be able to — through a process of many years and many meetings — to settle on the words and pictures and put it all together,” said Beverly Boyko, collections manager at the Louisiana National Guard Museums, which oversees the site.

Located on the site of Jackson Barracks’ original cemetery, the new memorial green space contains benches and five historic markers interpreting the history of the site and the people buried there. Civilians can organize a visit by contacting the Jackson Barracks Military Museum.

The remains of the Seminole woman were repatriated on the site several years later during a ceremony led by the Seminole Tribe of Oklahoma. Another repatriation ceremony for additional remains of unknown origin was held last November during the dedication of the memorial green space. The memorial, designed by landscape architecture firm Dana Brown & Associates, contains benches and five historic markers with text and images explaining the history of the site.

“(Andrew) Jackson’s name and the actions he took towards Native people will never be forgiven by s’cate (Native) people,” said Brian Thomas Palmer, assistant chief of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, speaking at the memorial dedication ceremony, according to a transcript of the event. “However, this ceremony at Jackson Barracks will heal wounds and restore dignity to our warrior brothers and sisters that were lost on the Nene Estemerkvlke (Trail of Tears) and the forgotten others interned here. The care being shown by those watching over them is moving and now they may rest.”

“While I cannot change the past, I can affect the present and the future, at least when it comes to Jackson Barracks and the Louisiana National Guard, and I am honored to pay respects to those of all backgrounds who perished and were buried on these grounds,” said Maj. Gen. D. Keith Waddell, adjutant general for the Louisiana National Guard, according to a transcript of the ceremony.

The memorial is in a restricted area at Jackson Barracks, but civilians can arrange a visit to the site through the Jackson Barracks Military Museum. The free museum interprets Louisiana’s military history through the lens of the Louisiana National Guard and will soon have an exhibit explaining the recent discovery of the cemetery and the site’s role in the forced relocation of Native Americans. Visit geauxguardmuseums.com to learn more.

Davis “Dee” Allen is PRC’s Communications Associate and a staff writer for Preservation in Print.

Advertisements