This story appeared in the February/March issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Urbanism has a geography — that is, a set of spatial trends — and those patterns vary by place and time. Some cities are envisioned and planned from Day 1; most others materialize incrementally, at crossroads, confluences, or heads of navigation, and get off to spasmodic starts before planners intervene to impose order. If they manage to persevere, some such settlements may grow into modern metropolises through any number of geographical drivers and sequences.

Consider New Orleans, which was envisioned (in 1717) before it was established (in 1718) and endured four years of unplanned building before a hurricane cleared the way for an engineered city (in 1722), today’s French Quarter. Over the next 170 years, the East Bank of New Orleans urbanized in a core-to-periphery pattern, the core being the bourg (French Quarter), and the periphery comprising numerous faubourgs (suburbs), spreading upon the natural levee of the Mississippi toward the banlieus (outskirts).

Advertisement

Other areas developed with different spatial thrusts. What we now call New Orleans East, for example, developed not from the core outwardly, but from the periphery inwardly. That is, railroads were built along the basin’s Lake Pontchartrain shore in the 1870s and along its Gentilly Road tier in the 1880s; after drainage systems dewatered its marshy core in the 1910s and hurricane-protection levees went up in late 1960s, subdivisions arose in the middle of the basin in the 1970s — even as it subsided below sea level.

Metairie and Kenner also lacked a core-to-periphery urbanization geography, and instead generally emanated from the river to the south and from New Orleans proper to the east, once the backswamps of Orleans and Jefferson parishes were drained in the early 1900s.

Then there is the West Bank, whose historical urbanism was perfectly liminal. I would describe its geographical growth over the long 19th century as shaped like a necklace, with a number of “beads” (tiny urban enclaves, really villages), but no pendant (that is, no true city), each of which grew and eventually merged and expanded — at which point the 19th-century string of villages became subsumed into 20th-century suburbia.

Growth of the West Bank. Map by Richard Campanella from “The West Bank of Greater New Orleans.”

Growth of the West Bank. Map by Richard Campanella from “The West Bank of Greater New Orleans.”

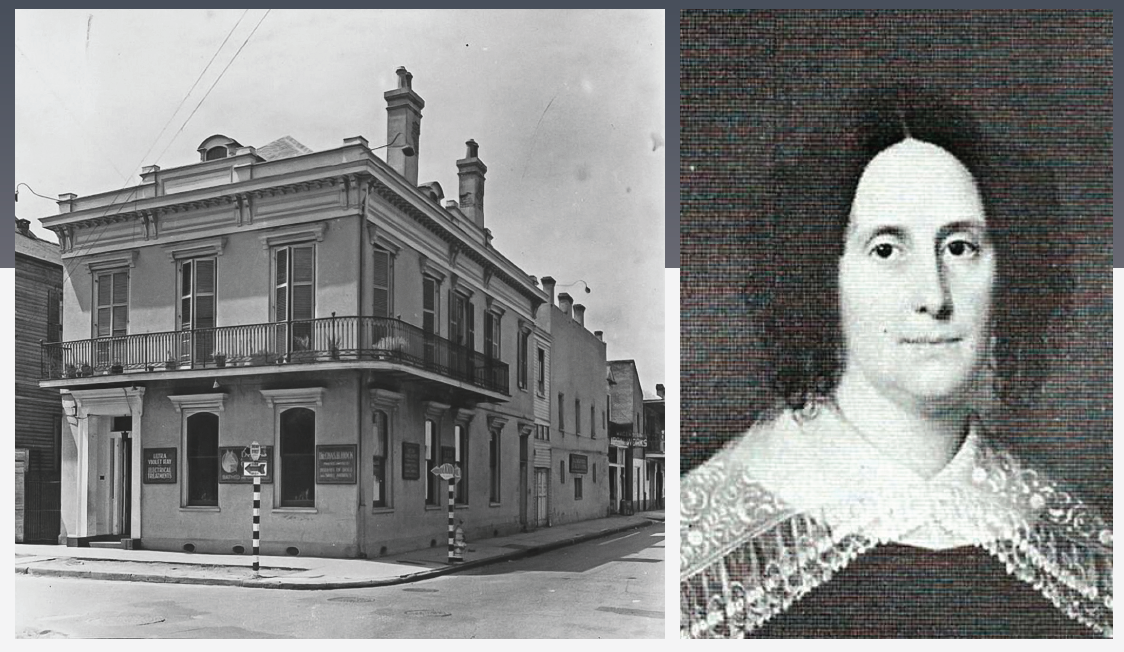

To understand how this happened and why it differed from the East Bank’s urban geography, consider some basic aspects of West Bank history. For one, the West Bank never had a bourg — that is, an original town, the equivalent of the French Quarter. We tend to think of Algiers Point as playing that role, and its residents speak proudly of being “the second oldest neighborhood in New Orleans,” dating to 1719. But in fact, that settlement originated as a work compound, warehouse, slave prison and company plantation, and did not attain a street grid — arguably a requisite to qualify as “urban” — until 1821, as Duverjéville, by which time McDonoghville had already been subdivided for seven years.

Secondly, the West Bank was overwhelmingly rural throughout the early 1800s, accessible by vessel from across the river or via canals through the Barataria Basin. The location of ferry landings and canal heads proved more influential in seeding new subdivision development than lateral expansion from Duverjéville (Algiers) or McDonoghville. This lingering bucolic ambience subjected the West Bank to very different developmental vectors compared to the higher-density East Bank, where space was at a premium, property values were high, and pedestrian-scale proximity drove real estate development.

Thirdly, railroads, which first came to the West Bank in the 1850s and helped make it into a transportation and industrial hub, served to link the necklace of villages even as plantations and farmlands still separated them. But because the railroads didn’t link to urban centers in New Orleans proper for lack of a bridge, the trains failed to inject new populations, and thus did not catalyze much urban growth. Rather, they conveyed commodities such as timber and cattle, and served more to boost industry than urbanization.

Finally, the West Bank’s sub-rural geography meant that municipal incorporation came late to its communities, starting no earlier than 1870 and continuing past 1950. Among other things, incorporation imparts official boundaries and a legal as well as cultural sense of residency, and until such municipalities came to the West Bank, clean lines and clear community identities were the exception rather than the rule.

Advertisement

Denizens thus perceived and named their spaces with a multiplicity of overlapping designations. The U.S. Census Bureau now uses the term Census-Designated Places to describe such unincorporated population clusters, but with no convenient handle in times past, observers loosely described them as hamlets, enclaves, settlements, subdivisions, towns or villages, that last one being the term (bourgades in French) used most frequently by West Bankers themselves. “Villages” were not wholly informal spaces; in the mid-1800s, the Jefferson Parish population clusters (wards) which people often called “villages” did have the right to elect three public works commissioners to represent local needs. But ward lines frequently changed, and no state legislation formally decreed these “villages” to have legal standing in the eyes of the law.

All this gave the 19th-century West Bank a human geography that more resembled a painter’s sfumato than a bureaucrat’s map, where villages bled into fields, suburban became sub-rural, farms blurred with plantations, and industries abutted pastures. Most boundaries were fuzzy, and toponyms were as soft spatially as they were orthographically — enough to drive a copy editor crazy. One person’s Durvejéville (or is it Duvergsberg?), for example, might be another’s Algiers (a term dating to the 1830s), which itself could, in certain historical uses, imply everything from Gretna to English Turn, else only Algiers Point (a more recent modification) — unless it was before 1830, in which case people might have called it Pointe St. Antoine, Punta San Antonio or Pointe Marigny.

McDonoghville (or Macdonogh or MacDonough?), which by some standards feathered into Algiers and Gretna, also went by Freetown and Gouldsboro. Tunis or Tunisburg got renamed Leesburg or McClellanville and were later subsumed into Algiers, whose name now shares the map with Aurora and Cutoff — until you cross the Algiers Canal (a.k.a. the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway Alternative Route), which gets you to the Lower Coast of Algiers (except for the subdivision named English Turn — or is that a river bend?).

This Army Air Corps photograph from 1923 captures the subrural nature of the West Bank, at top, prior to the construction of the Greater New Orleans Bridge. Image from Richard Campanella’s personal collection.

This Army Air Corps photograph from 1923 captures the subrural nature of the West Bank, at top, prior to the construction of the Greater New Orleans Bridge. Image from Richard Campanella’s personal collection.

It got worse. Today’s Gretna started as Mechanickham (Mechanikham? Mechaniks Village? Mechanicsville?) and was followed by another development explicitly named “Gretna,” to which were added a New Mechanickham and New Gretna before becoming, en toto, the Town of Gretna and finally the City of Gretna in 1916. As for Harvey, it was originally Cosmopolite City; Westwego was also Salaville; Marrero began as Amesville, and Bridge City was originally Belt City.

Nowadays, there’s little agreement on where and how McDonogh and McDonoghville straddle the Orleans/Jefferson Parish line (the line actually slices right through some houses), and at what point does the latter fall within Gretna — which begs the question, incorporated or unincorporated Gretna? So vexing was that confusion in Terrytown (created in 1960 in the back of John McDonogh’s property, later Oakdale) that frustrated neighbors ran a “Terrytown, Not Gretna” campaign just to get their mail delivered.

Marrero lies between Harvey and Westwego (which was a rail hub heading west — West We Go! — before it officially incorporated as a town and later a city — except, of course, for unincorporated Westwego). It extends down through Estelle and the “back of Ames” nearly to Crown Point and Lafitte (legally incorporated as a “village” — as opposed to Grand Isle, which is a “town”). That legal distinction came courtesy of the 1898 Lawrason Act, which stipulated that an incorporated village must have under a thousand people; a town, between 1,000 and 5,000, and a city more than 5,000 — though it said nothing of what to call unincorporated population clusters.

Advertisement

The spatial nomenclature of the West Bank grew even more complex with the advent of modern suburban subdivisions, whose corporate brands may or may not accord with neighborhood sobriquets, incorporated city limits, parish lines or voting districts, much less with historical names.

Toponyms for early West Bank subdivisions usually had burg or ville suffixes. The term faubourg, which was de rigueur for the inner suburbs surrounding New Orleans proper, was rarely if ever used on the West Bank, simply because there was no original urbanized core (-bourg) of which these subdivisions would be outside (fau-). Nor was the term banlieue (outskirts) used here, as it was on the East Bank, probably because the entire area would have qualified as such. Instead, the land mass was simply the “right bank” to the people who lived there, and “across the river,” “opposite the city,” or “over the river” to the people who didn’t. The term West Bank did not become standard until the late 1900s, and for a while folks also called it the West Side.

What helped converge the terminology of the West Bank’s gazetteer was the same infrastructural change that reworked its urban geography: the Greater New Orleans Mississippi River Bridge, which opened in 1958 and gained a second span in 1988. Daily commuting and a massive inflow of city dwellers relocating from across the river transformed that historical “necklace of villages” into the modern suburban conurbation it is today.

Yet if one looks carefully, one can still find vestiges of earlier geographies — a few remaining truck farms and cattle pastures, some plantation-era relics, that railroad coursing along Fourth Street since the 1850s, and beautiful historic architecture in the older parts of the “beads” of that necklace. Every time I stroll around the quieter streets of Algiers Point, McDonoghville, Old Town Gretna and Salaville, I find myself saying, “this feels like a village” — because they were.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; Cityscapes of New Orleans; Bourbon Street: A History; and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or@nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements