This story appeared in the October issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

From the outside, the new Sazerac House at the corner of Canal and Magazine streets is a 19th-century gem, with the building’s Italianate details restored to their original grandeur. Step inside, and visitors are immersed in a state-of-the-art facility that elegantly blends historic architecture with multimedia exhibits celebrating New Orleans’ storied cocktail culture.

When the Sazerac House, at 101 Magazine St., opens to the public on Oct. 2, visitors and locals alike will be able to delve deep into the history of the Sazerac cocktail at this free interactive attraction and headquarters for the Sazerac Company.

The first three floors feature vintage artifacts and interactive displays highlighting the distilling process and the company’s product line. The facility will produce Peychaud’s bitters, rum and Sazerac Rye whiskey on site, offering plenty of free tasting opportunities for guests throughout the space. The exhibits were designed by Gallagher & Associates, who also created exhibits for the National World War II Museum, and were locally fabricated by Solomon Group. The building’s fourth floor houses an event space, and the fifth and six floors house company offices.

The new facility is “located just a few short blocks from the site of the original Sazerac House —where the Sazerac cocktail was available to guests and the inspiration for the name of this homeplace,” said Miguel Solorzano, general manager of the Sazerac House.

Opening in 1852 in the French Quarter, the first Sazerac House was a coffee shop that popularized a version of the cocktail made with brandy, absinthe and Peychaud’s bitters. (The bitters were created by Antoine Peychaud at a nearby apothecary.)

The original coffee house was demolished in the late 19th century, but it laid the foundation for the cocktail and the company. Rye whiskey and Herbsaint eventually replaced the brandy and absinthe, as the drink became ingrained in New Orleans culture over the years.

Restoring an architectural ensemble

After the extensive renovation, this corner of Magazine and Canal streets gleams anew, but the property had sat vacant and deteriorating for 30 years prior to being purchased and rehabilitated by the Sazerac Company.

The Sazerac House has the appearance of two combined buildings, but it was initially three when the structures were built in the 1860s. In the late 19th century, two four-story buildings on Magazine Street were combined, and a fifth floor was added, creating the larger building of the architectural ensemble. Then, in the early 20th century, the third four-story building facing Canal was connected through the party wall.

Over the years, the buildings’ tenants included dry goods stores and a hat and glove manufacturer. Today functioning as one building, its exterior retains original Italianate features, including arched window openings, window hoods and cornices with brackets, dentils and parapets. A sixth story was added during the renovation for the company’s offices, with careful consideration to site lines to reduce its visibility from the street.

“Our inspiration was to showcase our products, to showcase the history that we have, and the fact that we date in New Orleans back to the 1850s,” Solorzano said. “This has been our home ever since, and we now want to make sure that people recognize that.”

To reimagine the long-vacant buildings and create a new “homeplace,” the Sazerac Company engaged Trapolin-Peer Architects in December 2015. The buildings had a number of structural issues after 30 years of vacancy, including foundation settlement, and termite and water damage. Remediating structural issues was the first order of business, and Trapolin-Peer enlisted the expertise of Ryan Gootee General Contractors and Morphy, Makofsky, Inc. engineers, among others, to help revive the structure.

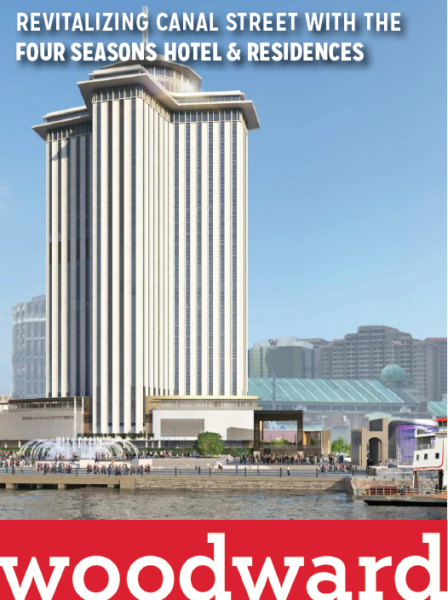

Advertisement

“There were entire floors we couldn’t walk on to begin getting dimensions of the building,” said Shea Trahan, associate at Trapolin-Peer Architects and the project architect. “We had to have the whole structure 3D scanned.” The scanning process revealed that the floors were up to eight inches out of level in some places. Due to height limitations for the planned sixth story addition, contractors had to simultaneously make accommodations to the roof plane as each floor was releveled to ensure the final roof height remained the same. Wood framing had to be restructured, and masonry walls had to be tuck-pointed and restored — some receiving a grout injection for stabilization.

Restoring the building’s historic features was also a top priority for the renovation, which was powered by historic rehabilitation tax credits. On the exterior, most of the original storefronts had been replaced in the late 20th century with aluminum. “We were able to locate some of the original three-leaf wood storefronts, so we were able to have a model by which to replace them all and know that we were doing so historically accurately,” Trahan said.

Between the storefront openings were cast iron pillars that originally had ornate acanthus leaf capitals, but the classical ornamentation had been stripped from the building. Upon closer inspection, architects discovered a single surviving acanthus leaf detail on one of the pillars, which had been hidden behind a plumbing line for years. Taking a mold from the remaining acanthus leaf, cast iron replicas were placed on the capitals of the pillars.

The facade of the smaller four-story building had been reconstructed in the late-20th century. Though the alteration reused some pieces of the original structure, its Italianate cornice with brackets and dentils had been lost. Using vintage photographs found at The Historic New Orleans Collection, architects meticulously reconstructed the cornice out of glass-fiber reinforced concrete — a sturdy yet relatively lightweight construction material.

On the interior, original columns punctuate the space – fluted cast iron on the first floor and heavy timber on the upper floors — and were retained and restored. Historic brick pavers that were discovered beneath the foundation during structural remediation were salvaged and reused as flooring in the building’s new atrium and retail space.

Advertisement

A showstopper of the building is the historic cypress and mahogany staircase, which winds its way from the first to the third floors. Since its narrow winders are not permitted for commercial uses today, the staircase sits as an architectural artifact roped off from guest access. Although heavily deteriorated before the building’s renovation, the staircase was considered a critical historical element to the structure. “It was taken apart piece by piece, cataloged, and brought to our master woodworker shop, where they restored it,” Trahan said.

The staircase historically went up five floors, but the salvageable material allowed for only three levels of reconstruction. All of its mahogany spindles were recreated.

Because the staircase can no longer be used by guests, a new set of steps was added with a modern design that respects the past while celebrating the Sazerac brand. The treads are built from the floor joists that were removed to make room for the new stairwell. Its ornate railing is inspired by the ironwork of the Pontalba Buildings and incorporates details such as the star anise flower, a signature component of Peychaud’s bitters.

Instead of executing the design in cast iron, the railing was plasma cut from three-eights-inch steel plates. “We integrated the Sazerac Company’s identity in a material that is unapologetically contemporary, but also gives a nod back to the history of the place that it’s in,” Trahan said.

Sazerac branding also found its way into new details in the entry vestibule. A hexagonal tile floor with the company logo is beneath visitors’ feet, and a detailed plaster medallion with a chandelier is above their heads. Working with Formglas, an architectural sculpting company based in Canada, the architects went through many design iterations of the medallion to incorporate acanthus leaves, the Sazerac “S” and star anise pods into the plaster relief.

“In all of our modern interventions within the building, we really strove to integrate the architectural history as well as the company history,” Trahan said. “The medallion is a perfect example of how these two things come together.”

The historic cypress and mahogany staircase was taken apart piece by piece, cataloged and meticulously restored. A new staircase has an ornate railing inspired by the ironwork of the Pontalba Buildings and incorporates the star anise flower, a component of Peychaud’s bitters, into the design.

Bringing history into the future

The building isn’t only a celebration of the past, though. “All along the way, this historic building has been incredibly high tech,” Trahan said. The architects paid close attention to the acoustics to prevent noise from disrupting the guest experience or offices during events.

A state-of-the-art fire protection system continuously samples the air and can trigger an alarm minutes before combustion takes place. The distillery’s piping and mechanical systems are so complex that virtual reality headsets were used to coordinate their placement.

The distillery is a feat of engineering in its own right, and the project’s designers worked closely with Moses Engineers and distilling experts at the Sazerac Company to ensure the space would meet the needs of whiskey production. A new 500-gallon copper still is two stories tall and was custom made in Kentucky by Vendome Copper & Brass Works. An independent structural system was created to hoist the still into place through the four-story portion of the building as its facade was being rebuilt. Hidden beneath the distillery’s raised access floor, a vinyl waterproof flooring membrane drains to the exterior to prevent damage to the museum exhibits in case of spills.

Even with its state-of-the-art new additions, architects estimated that 10 million pounds of building material were kept out of the landfill by rehabilitating the vacant building instead of building anew. “When we equate that to other carbon footprints, it’s equivalent to removing 543 cars from the road for an entire year or providing electricity to 446 homes for an entire year,” Trahan said.

Perceptive visitors will pick up on the winks and nods to the signature cocktail, spotted in the star anise architectural details and white oak flooring inspired by bourbon barrels. Grand architectural flourishes, including a glowing three-story wall of spirits bottles and a two-story whiskey still, are sure to capture the attention of passersby on Canal Street through the windows, and could likely be landmarks on the street for years to come.

“It’s hard to imagine what a cocktail might look like in architectural form, but I hope somehow we’ve captured that essence,” Trahan said.

Davis “Dee” Allen is PRC’s Communications Associate and a staff writer for Preservation in Print.

Click to expand images

Advertisements