This story appeared in the September issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

The photograph always perplexed me: a circa-1858 streetscape captured by Jay Dearborn Edwards of a scene evocative of the Coliseum Square area or perhaps the wider arteries surrounding the Garden District, like Jackson or Louisiana or St. Charles. It shows a row of eight brand-new double-gallery Greek Revival townhouses, freshly whitewashed, with ample gardens, delicate trellises and recently planted trees — a district of gardens indeed, and with neighbors posing out front, a rarity for antebellum photography.

What’s puzzling about Edwards’ shot is that it was taken on a street that was muddy at the time, “back” of town, near the swamp, and far from most of antebellum New Orleans’ spaces of prestige and convenience. It was Claiborne Street, specifically today’s 200 block of South Claiborne Avenue, now a concretized meta-scape of speeding motorists and encamped vagrants on which even the most utilitarian buildings turn their backs.

What Edwards captured was the culmination of a civic improvement effort that daringly defied just about every tenet of local urban geography, circa-1850s: that topography, hydrology, and proximity matter; that power and prestige don’t want to socialize with their opposites, and that nuisances drive down land values, after which expediency wins the day.

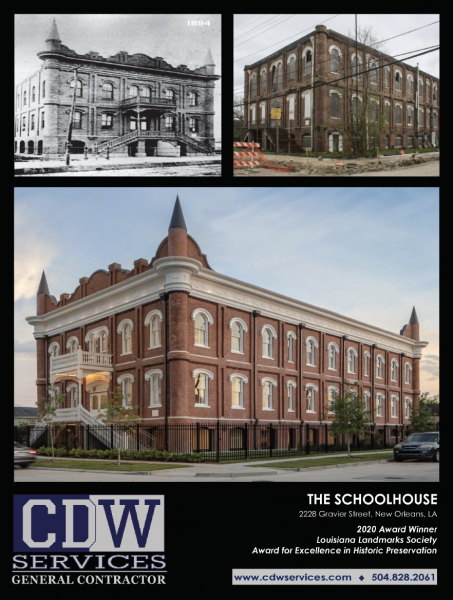

Advertisement

At the time of the city’s founding, what is now the Claiborne corridor roughly marked the rear of the backslope of the natural levee, beyond which water became impounded and cypress swamps prevailed. This was not a fixed condition; during the drier months and when river stage dropped, swamp water receded a few thousand feet, while wetter periods could bring the morass closer to today’s Rampart Street, which is where some colonial maps put their marshy hachures. Note that Marais Street, marais meaning marsh, runs precisely between Rampart and Claiborne.

What New Orleans’ deltaic hydrology meant for urban geography was the formation of a perceptual “front” and “back” of town. Places of power tended to get positioned in the front (e.g., the Place d’Armes) whereas their antithesis got relegated to the rear (e.g. the cemetery). Over time, these divergent land uses, and their attendant human settlements, reiterated the underlying topographical variability, such that by the antebellum era, every New Orleanian knew the implications of the “front” versus “back” of town, be they hydrological, social, economic, racial, epidemiological, or psychological.

Jay Dearborn Edwards’ photograph of the eight Greek Revival townhouses on what is now the 200 block of South Claiborne Avenue, taken probably in 1858 but possibly as late as 1861. Photo courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Accession No. 1982.32.13.

This is not to say that blocks closest to the Mississippi were the richest; this being a working river, maritime land uses and blue-collar demographics prevailed along the immediate riverfront, driving the tony away. Rather, it was in those areas a few blocks behind the riverfront where wealthier precincts arose, among them Coliseum Square and the Garden District.

An opportunity came for real estate investors to challenge these patterns starting in the 1830s. For one, urban expansion had extended the metropolis four miles upriver and two miles downriver, a long way from the urban core. Anyone who figured out how to de-stigmatize cheap spaces that were barely a mile back of town could turn a tidy profit if they improved them with fine housing and amenities.

As for the backswamp, well, starting in 1835, the New Orleans Draining Company had installed the city’s first-ever mechanized pumps — steam-driven paddle wheels mounted on tributaries to Bayou St. John, which sped the discharge of runoff within hydrological subbasins that had been halved in size thanks to the transecting construction of the New Basin Canal during 1832 to 1836. Hardly did the paddle pumps reclaim the backswamp, but they did reduce standing water enough to dry out Claiborne Street, an artery first laid out in the early 1820s, enabling it to be extended in both directions.

Advertisement

The hydrological changes could be seen on the growing city’s showcase corridor of Canal Street, where surprisingly opulent residential development progressed further and further back. Among them was Union Terrace, on what is now the 900 block of Canal, designed by architect James Dakin to emulate Manhattan’s fancy Lafayette Terrace and completed in 1837 at a cost of $100,000. Directly across from the State House and only a block from what would soon become the University of Louisiana (today’s Tulane University), Union Terrace inspired the construction of a number of attractive townhouses erected closer and closer toward Claiborne. What had previously been mapped as marshy was now practically rivaling parts of uptown as a prestigious address.

As for the back-of-town housing prevalent nearby, a terrible blaze in 1844 destroyed hundreds of wooden cottages and caused upwards of $600,000 of damages. The so-called Fourth Ward Fire (ward enumeration has since changed) cleared most of the blocks bordered by Canal, South Claiborne, Common Street (now Tulane Avenue), and South Rampart — a tragedy for many, but like many disasters, an opportunity for others. Within a few years, real estate interests seemed convinced that Claiborne was poised for a flipping.

“Choice property” on what is now 200 South Claiborne started to sell at auction, according to a November 1852 piece in the Daily Picayune, as vendors uptalked “this very valuable real estate…near the new market on Claiborne street,” an open pavilion on the neutral ground intended to serve this “most improving portion of New Orleans.”

226-234 South Claiborne, captured by Walker Evans in 1935. Courtesy of Walker Evans, Private Collection at the Florence Griswalk Museum.

New residents started to complain of conditions once expected for the back-of-town, such as delays in the completion of the Claiborne Market (June 1853), and all the hogs and goats uprooting banquettes, as reported under the January 1855 headline “The Claiborne Street Nuisances.”

Complaints about these and other problems, namely drainage, seemed to have their effect. In May 1855, the Daily Picayune raved about the progress, even putting the area toe-to-toe with uptown: “Claiborne Street — Few of our up town residents we suspect are fully aware of the present beautiful appearance of Claiborne Street. The public ground in the centre is in many respects the handsomest in the city… with its deep clean green sward and four symmetrical rows of handsome trees in the full bloom and freshness of the summer foliage.” This was the first mention of the oaks that would become famous on Claiborne in the century ahead. “The trees have attained a considerable size, thickly set [and] very luxuriant. This public ground gives to this street a most inviting aspect for residences.”

Speculators agreed, and over the next few years, they contracted builders to erect a row of eight nearly identical Greek Revival townhouses, along with a number of comparable residences, all on the river side of what is now South Claiborne, from Common (now Tulane Avenue) to Gasquet (now Cleveland Street).

Advertisement

On a wintry day probably in 1858, Jay Dearborn Edwards came along with his tripod-mounted camera and captured the elegant row, whose stately Classical galleries — fortuitously visible thanks to the leafless trees — stand in contrast to the muddy street. At the left edge of the frame one can see the overhanging eave of the Claiborne Market, and in subsequent scenes, Edwards photographed the market itself, and Common Street looking toward the river from the same block.

In 1859, likely prompted by that new row of upscale townhouses, the city adopted a resolution to “open Claiborne street,” meaning to extend its trajectory upriver from the Claiborne Market, a move that had “long been desired by a large and influential portion of the inhabitants of the city, and will bring improvement [to] valuable property now lying idle.”

They were right. Claiborne would be opened, upriver (“South”) and downriver (“North), redesignated as an avenue, and spanning the entire city, from the Jefferson to the St. Bernard parish lines. Businesses and residences would sprout up along it by the hundreds, as modern drainage pumps dewatered the backswamp, as urbanization stretched lakeward, and as automobiles came to dominate the streets. Claiborne became convenient in both its width and position to became a trans-urban thoroughfare.

In this early-1960s aerial photo, the last of the 1850s townhouses may be seen at center, facing the neutral ground, a few years prior to their demolition for the Tulane Avenue on-ramp to the elevated expressway. Courtesy of Richard Campanella’s personal collection.

Indeed, just about every vision contemplated for Claiborne in the 1850s came true by the early 1900s — all but one, that it. Its downtown section never sustained the upscale development momentum initiated by that elegant row of Greek Revival townhouses photographed in 1858.

Instead, the “back of town” prevailed, and the evidence was all around. Just a few hundred feet away, and built two decades earlier, was Charity Hospital, positioned in an era when spaces for the ailing were viewed as nuisances. Just across the street from Charity was the biggest nuisance of all, the city’s gas works, where since 1833, coal was super-heated in gigantic vats to release methane, hydrogen, and carbon monoxide, which was then purified, stored in tanks, and piped to subscribers for cooking and illumination. An ominous-looking operation emitting smoke, ash, tar, and highly combustible syngas, the New Orleans Gas Works drove down property values all around, which invited other industrial land uses. All this conspired to make this area a place of relegation in terms of residential occupancy, where the poor and marginalized ended up, predominantly African Americans only a generation removed from slavery.

People of means, especially moneyed white families with upward social aspirations, had no desire for an address on this part of South Claiborne Avenue. Real estate interests instead shifted to accommodate the growing medical district, and that row of antebellum townhouses became an island of fading grandeur in a sea of gritty functionality.

When another noted photographer — Walker Evans, working for the New Deal-era Resettlement Administration — happened by 226-234 South Claiborne in 1935, his camera captured three of the aging antebellum townhouses, others in the row having been demolished. They were still stately, but worse for the wear and in need of a paint job. One had a rooms-for-rent sign, and, unlike that 1858 photo, now there was nary a soul in sight.

The last of the eight enigmatic townhouses of 200 South Claiborne met the wrecking ball in the mid-1960s for the upcoming Claiborne Expressway — the same expedient infrastructure that would destroy the Claiborne oaks, first planted in the 1850s, and that would eventually upheave the predominantly African American community of Tremé further down on North Claiborne Avenue.

If you’ve ever driven up the Tulane Avenue on-ramp to Interstate 10, you passed right through the spaces of their former parlors.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; Cityscapes of New Orleans; Bourbon Street: A History; and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or@nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements