Within these Walls

Biographical portraits of New Orleans residents and their homes

This story appeared in PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Dr. Delphine Mayronne, a certified osteopath, practiced in New Orleans for more than 20 years. The home at 930 Valmont St. was her last known address and the location of her final practice.

Delphine had an unlikely beginning for a suffragist and practitioner in a new medical field. Her father, Onesiphore François Mayronne, was the son of a wealthy planter in St. Charles Parish. Her mother, Margaret Eberly, was a Pennsylvania native and the daughter of a physician.

Delphine grew up on Ellington Plantation in Luling, in a home designed by Charles Gallier. She was surrounded by her parents, grandparents, five siblings, countless aunts, uncles and cousins, and the many individuals enslaved by her family. As a child, she knew vast wealth.

After her grandfather’s death, her father inherited the plantation. During the Civil War, it was the site of skirmishes and was for a time confiscated by the federal government. Facing financial ruin, Onesiphore Mayronne purchased a farm in Arkansas. The venture did not last long. He died there in February 1867. Just a few months later, his wife died in New Orleans.

Orphaned at the age of 15, Delphine was forced to rely on the charity of her relatives. She and her younger siblings were taken in by her sister Marguerite and brother-in-law Judge Arthur Saucier. However, Saucier’s death in 1877 once again plunged the family into financial instability.

By 1886, Delphine’s sister Marguerite had done the unthinkable for a formerly elite Creole woman: she took a job. She went to work as a copying clerk for the Civil District Court to support herself and her children. Once again, Delphine found herself entirely dependent on relatives during a time in which opportunities for women were severely limited.

But that didn’t stop her. By 1895, she was in Butte, Mont., earning a living by teaching French. According to the local newspaper, she possessed “the purest Parisian accent,” as she taught her pupils. She was likely aided by friends of her late brother-in-law, who had been a founding member of the Athénée Louisianais, a literary society dedicated to preserving the French language. A few years later, she was on the faculty of Butte High School and listed as a graduate of the New Orleans St. Charles Academy. She even purchased land there. Yet Montana was not the final stop on her journey.

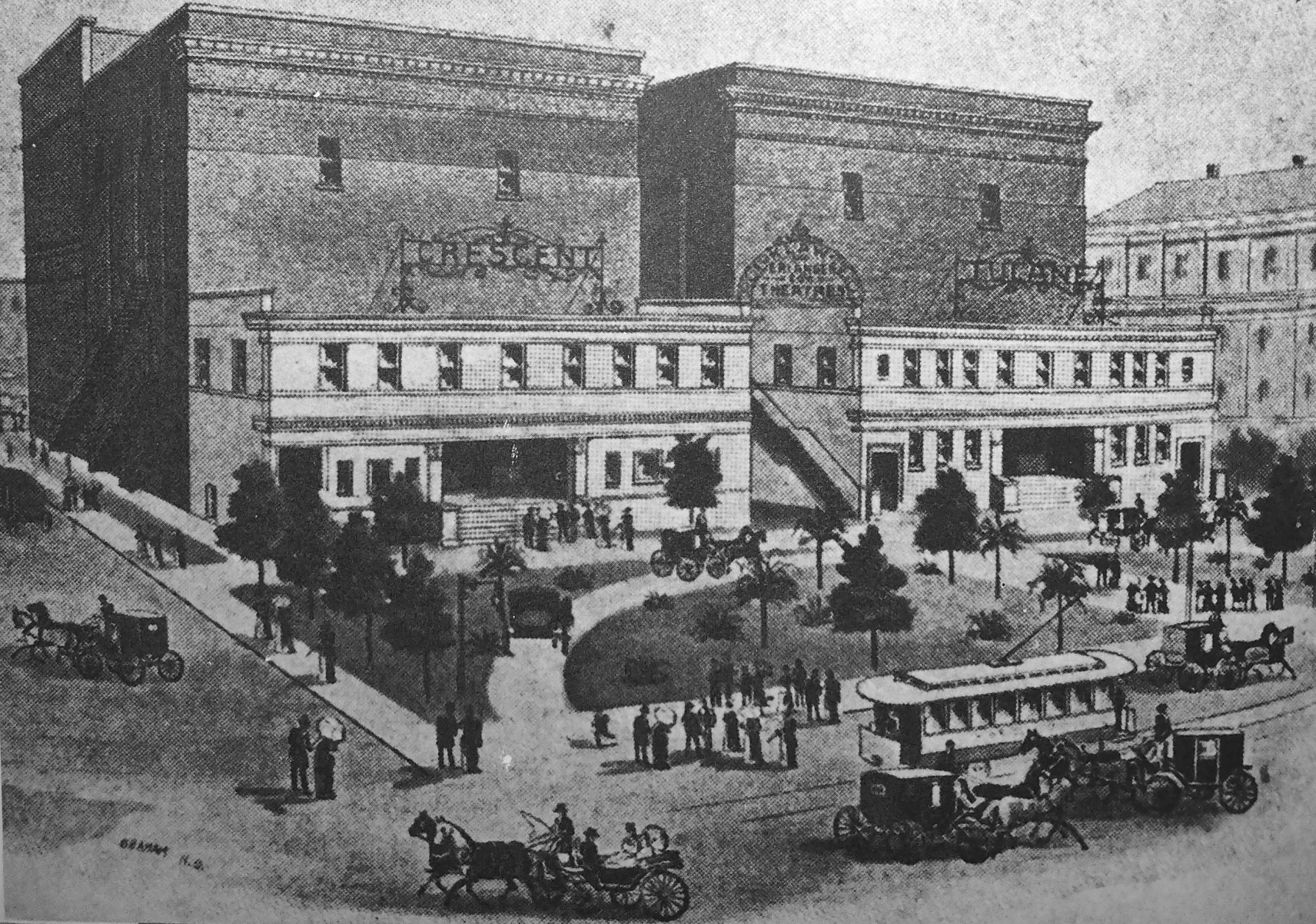

Ellington Plantation. Photo courtesy of scphistory.org

The Times-Picayune, January 30, 1915.

In the late 1890s, Delphine moved to Kirskville, Mo., and began attending the American School of Osteopathy. Founded in 1892 by A.T. Still, known as a magnetic healer and “lightning bonesetter,” the school emphasized the structural relationships of bones, muscles and organs, advocated for treatment without the use of drugs, and believed that correcting interferences with the free flow of blood in the body was key to health. Perhaps Delphine was inspired by stories about her grandfather, Dr. John Eberly, a surgeon at the battle of Baltimore during the War of 1812, who founded a medical college and authored many treatises.

Delphine graduated from the American School of Osteopathy on June 27, 1901, and headed home to New Orleans.

Upon arrival, she placed a newspaper advertisement announcing the establishment of her practice. A Daily Picayune ad on Nov. 30, 1902, described her as an osteopathic physician and New Orleans native with an office on Camp Street, “diseases of women and children a specialty.” She was in attendance at the first meeting of the State Board of Osteopathy in 1908 and registered with them at the meeting. That same year, she briefly left New Orleans for Atlanta, but returned by 1910.

Over the years, she had offices on Camp Street, Howard Avenue, Jackson Avenue, the Audubon Building, and, as she aged and her practice seemed to dwindle, at her own residences in rented rooms Uptown.

In 1912, she became a member of the Era Club, one of New Orleans’ most prominent suffrage organizations. It was also one of the largest women’s clubs in the South. She made financial contributions to the suffrage cause. Yet she appears to have struggled financially, turning to get-rich-quick schemes in an effort to support herself. She was charged with violating the lottery law in 1901. She also was one of many victims, mostly women, who invested in a phony railway company. She took them to court and became a leader in the fight for justice against the perpetrators.

When Delphine made her home and practice at her rented home on Valmont Street, she was 75 years old. Having never married, she had no children to turn to for aid. Her siblings were dead or soon would be, and her nieces and nephews had their own struggles.

As the nation entered an economic depression, Delphine experienced one of her own. Elderly, infirm and alone, she became an inmate at St. Anna’s Asylum for destitute women on Prytania Street.

The asylum had ties to the suffrage movement Delphine had championed. According to The Historic New Orleans Collection, when the court invalidated a bequest from a resident there on the grounds that women could not legally serve as testamentary witnesses, women challenged the system. The incident led suffragist Caroline Merrick to say, “The bequest went to the State — and the women went to thinking and agitating.” Thinking and agitating seem activities with which Delphine was familiar.

Sadly St. Anna’s was not to be her final home. She was committed to the state insane asylum in Jackson, La., some time after 1930, likely due to senility and dementia. She died there at the age of 84.

A one-sentence obituary was published on Dec. 18, 1932, her life commemorated with the words: “Dr. Delphine Mayronne entered into rest Saturday, December 17, 1932.”