Within these Walls

Biographical portraits of New Orleans residents and their homes

This story appeared in the June/July issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Magdalena Streitmuller Hilderbrand arrived in New Orleans when she was 14 years old. Born in Germany, Magdalena, her parents Anton and Catherina Streitmuller, and seven siblings boarded a ship in Havre, France, intent on settling in Missouri as farmers. On Christmas Eve 1846, they first caught sight of New Orleans and decided to stay.

When she was 17, Magdalena married J.D. Peters, but she became a widow with an infant daughter before her 20th birthday. In 1853, she wed Mathias Hilderbrand at Holy Trinity Catholic Church, a parish established specifically for German immigrants. Less than a decade after their marriage, the couple was raising five children: Caroline, Magdalena’s daughter from her first marriage, as well as the four Hilderbrand children, Charles, Frances, Catharine and Mathias Jr.

During the Civil War, most white men in New Orleans had joined the Confederate army. But Mathias defied popular opinion and enlisted in the United States infantry on July 28, 1862, just months after New Orleans surrendered to the Union in April 1862. He served as a private in Company B of the Louisiana Volunteers. He first came down with illness during the Bayou Teche campaign in the spring of 1863. While at Port Hudson, he participated in the longest siege in U.S. history during a bitter fight for the control of the Mississippi River. The Union army was victorious, but Hilderbrand emerged from the fight gravely ill. His dysentery proved so severe that he was sent to New Orleans on furlough. He died shortly after his arrival home, surrounded by his family.

Once again, Magdalena was a widow, this time with five children ranging in age from 3 to 12 years old. Shortly after her husband’s death, Magdalena applied to the federal government for a pension for herself and her children as the widow and minor children of a United States veteran. She was awarded $8 a month along with pensions for her children until they reached the age of 16. While certainly beneficial, these pensions were not enough to support her family. Magdalena worked at a cotton press. She and her younger children lived for a time with her eldest daughter Caroline after Caroline’s marriage. The family always struggled to make ends meet.

On March 4, 1873, Magdalena gave birth to a son whom she christened George Hildebrand. When registering his birth, she told the recorder that his father was Mathias Hilderbrand, which was, of course, impossible. Her husband Mathias had died a decade earlier. George would spend his entire life claiming that Mathias Hilderbrand was his father. The identity of his real father remains a mystery.

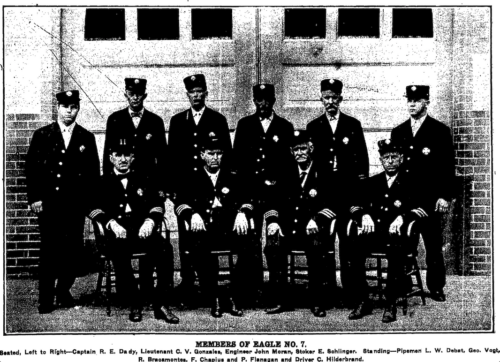

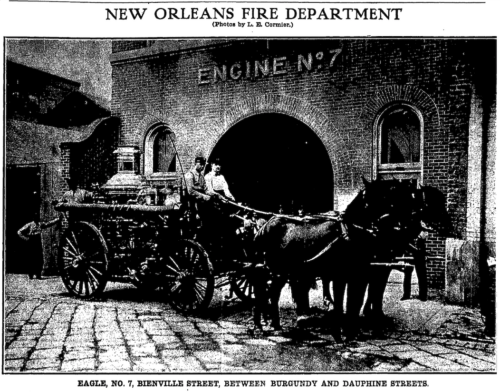

Charles George Hildebrand, the grandson of Magdalena Hildebrand, served for 33 years and attained the rank of captain in the New Orleans Fire Department.

As an impoverished mother and widow in a patriarchal society, Magdalena was particularly vulnerable. It was possible her youngest child was a product of a nonconsensual act. Another factor was Magdalena’s pension. If she remarried or cohabited with a man, the government would end her pension payments. Magdalena may have had a relationship she did not wish to reveal, thereby protecting her benefits. During the 47 years that Magdalena received a widow’s pension, examiners from the federal government routinely assessed her case. Not once was George’s name ever mentioned. His existence would remain unknown to federal bureaucrats.

Magdalene always lived in the Bywater neighborhood, moving from rental house to rental house every few years. Around 1890, she moved for the last time to 821 Pauline St. Though the Hilderbrands always rented the Pauline Street property, it became a permanent residence for them. Magdalena’s son George was a baker and confectioner and supported his elderly mother even after his marriage. For the last two decades of her life, Pauline Street was always Magdalena’s home, but it also served as a refuge for her children, grandchildren and her children’s in-laws.

As she began to experience more stable and comfortable living circumstances, Magdalena also was able to enjoy the success of her children and grandchildren. Charles Hilderbrand, her eldest son, joined the city’s first volunteer fire department in 1879. In December 1891, when it became the New Orleans Fire Department, a government entity offering paid jobs, Charles continued as a firefighter. He was a pipeman and the driver of a hose carriage.

Charles George Hildebrand, son of Mathias Jr. (and named for his two uncles), was also a member of the New Orleans Fire Department. He served for 33 years and attained the rank of captain.

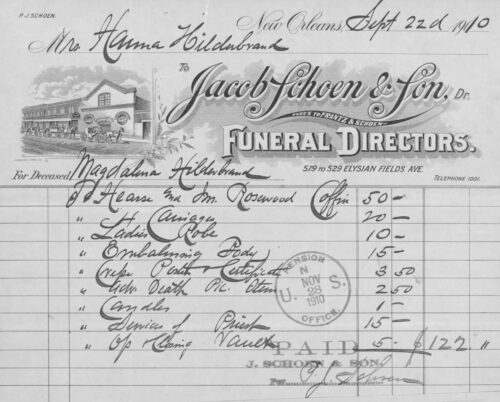

In August 1910, Magdalene began suffering with gastrointestinal issues, and her daughter-in-law summoned the doctor. She died at home on Sept. 20, 1910. Like her husband almost 50 years prior, her cause of death was dysentery. The undertakers Jacob Schoen and Sons managed the funeral, which took place from the Pauline Street residence. A priest accompanied family and friends to the interment in St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery (also known as Louis Street Cemetery). Magdalena was born in Germany, but she was laid to rest in the neighborhood where she lived and worked for most of her life.

A Sept. 22, 1910 bill from Jacob Schoen & Sons Funeral Directors shows the costs for the funeral of Magdalena Hildebrand.

A Sept. 22, 1910 bill from Jacob Schoen & Sons Funeral Directors shows the costs for the funeral of Magdalena Hildebrand.