Within these Walls

Biographical portraits of New Orleans residents and their homes

This story appeared in the December issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

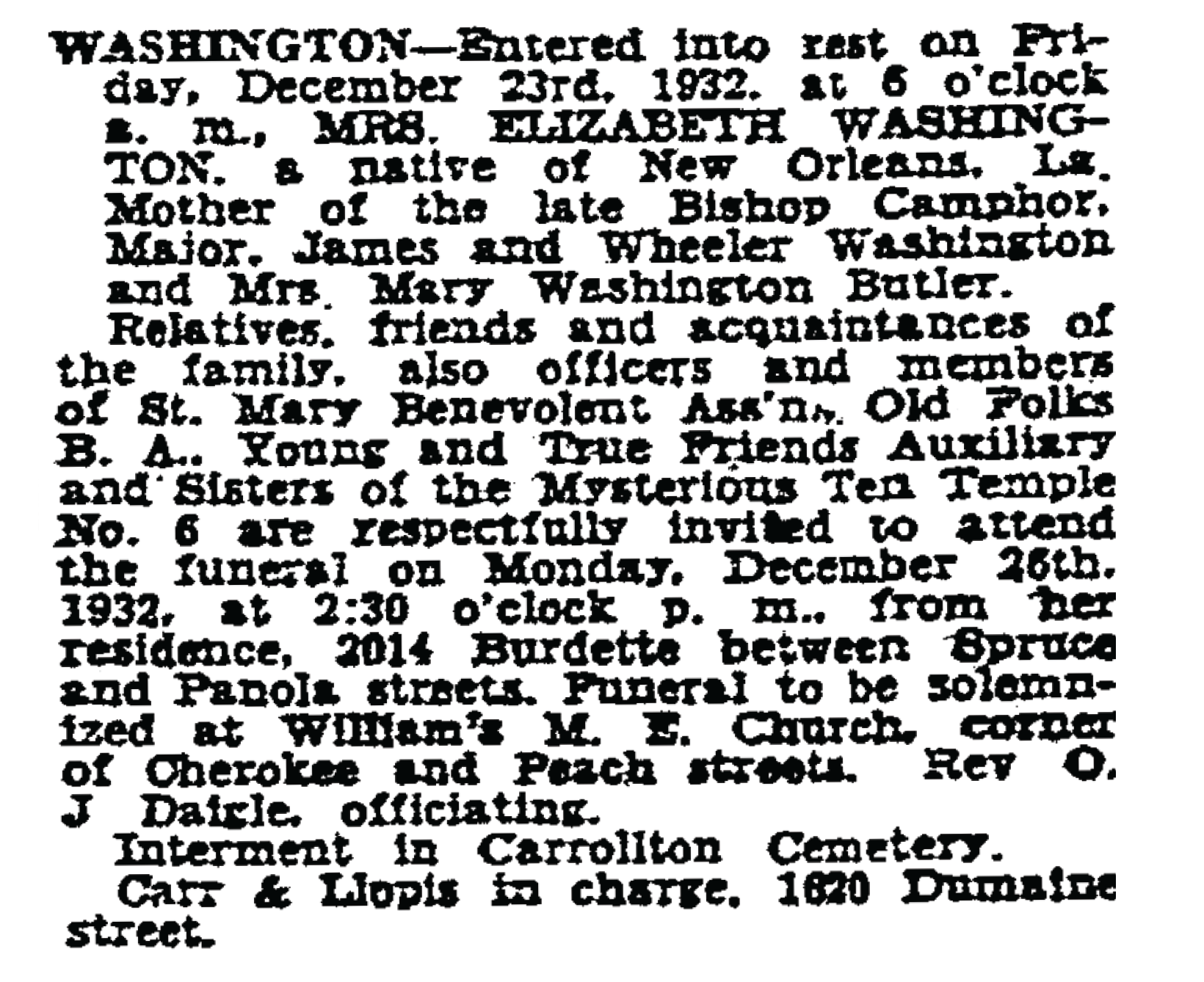

Two days before Christmas 1932, Elizabeth Jones Washington lay dying in her Burdette Street home. Though she had lived on the same plot of land for almost 60 years, her current residence at 2014 Burdette St. had only recently been built. In her final hours, she must have found comfort in the fact that she was leaving her children a home and two lots.

For the first two decades of her life, it had been against the law for her to own anything. As a formerly enslaved person, she had been considered property, listed in legal documents alongside real estate, furniture and livestock.

Born around 1842 on Jacques Telesphore Roman’s Oak Alley Plantation, Elizabeth was trained as an enslaved domestic. She was known as Thisbe during slavery. Most of her teenage years were spent in the Romans’ French Quarter home. In 1860, the Romans sold 18-year-old Elizabeth and her infant Chloe to neighboring plantation owner Alexis Ferry, separating her from her family and community.

In the midst of the Civil War, the Union army captured New Orleans and then sent federal troops into the River Parishes to pursue Confederate guerillas.

The arrival of Union forces on the plantations provided an opportunity for enslaved people to seek freedom. In the fall of 1862, Elizabeth and her daughter sought refuge at Camp Parapet, a Union army headquarters in Jefferson Parish. Enslaved people, known as “contrabands of war,” came there in the hundreds, and Camp Parapet quickly became one of the largest contraband camps in the South.

Unfortunately, disease spread rapidly throughout the camp. Perry Camphor, the father of Elizabeth’s children, died there. Around the same time, Elizabeth gave birth to a son, Alexander Camphor. She found herself alone in an army camp without any means of support and chose to lean on her faith.

Ross Chapel, a Methodist Episcopal congregation, had developed around Camp Parapet. Elizabeth was the first convert at the chapel. She became very close to Stephen Priestly, who had also been enslaved by Alexis Ferry. Priestly, a minister at Camp Parapet, was literate. His wife and child had been separated from him during the Civil War. Priestly remarried, but he and his new wife were never blessed with children. Priestly offered to take Elizabeth’s son Alexander into his own home and educate him.

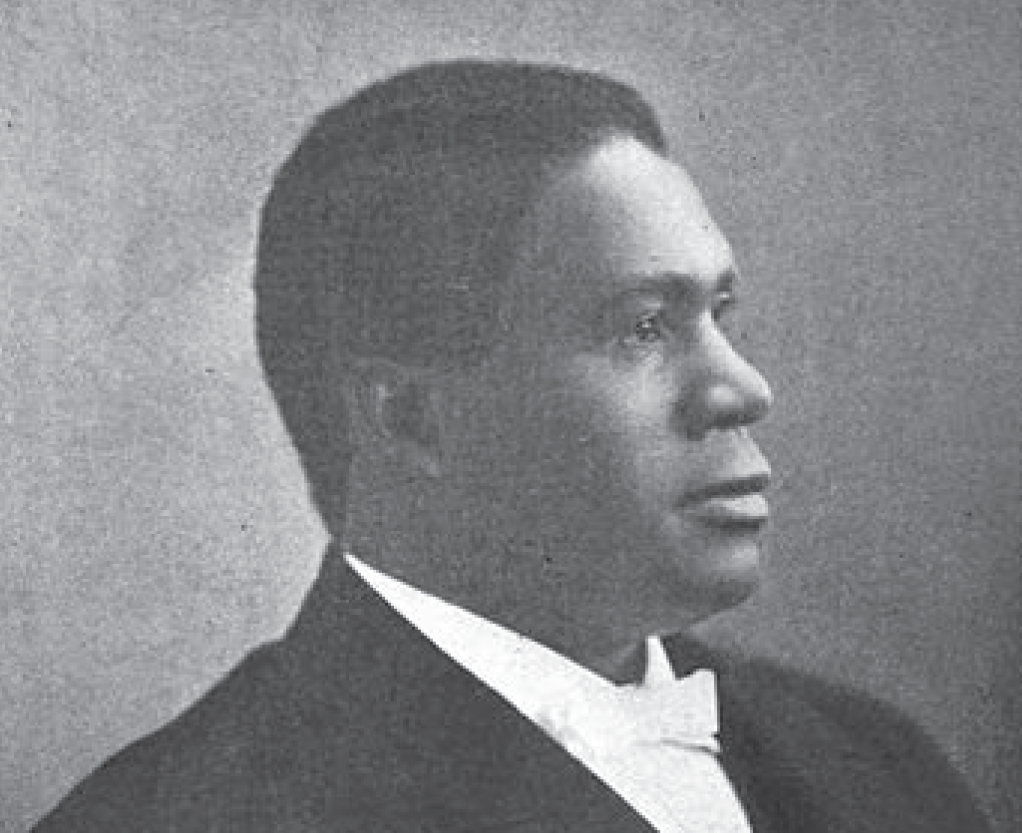

Photo 1: Rev. Dr. Alexander Priestly Camphor. Photo 2: A death announcement for Elizabeth Jones Washington. Courtesy of The Item-Tribune, Dec. 25, 1932.

Elizabeth remained in Jefferson Parish and worked as a laundress. She married Charles Washington, a laborer. She gave birth to around a dozen children; only eight survived to adulthood. Despite the many mouths to feed, the Washingtons managed to save a considerable amount of money, enough to buy their own home. In 1875, former planter Victor Fortier and his siblings began selling off property in the Carrollton neighborhood. Charles Washington bought five lots for $230 in cash.

The Washingtons’ property began on the corner of Burdette and Eighth (now Spruce) streets, bounded by Washington (now Fern) and Cypress (now Panola) streets. The Rev. Stephen Priestly, his wife, and Elizabeth’s son Alexander lived just a few blocks up Burdette Street.

Priestly kept his promise to Elizabeth and did everything he could for Alexander’s advancement. Priestly’s 1896 obituary described him as “one of the most prominent and able colored preachers in the state,” and noted that his funeral was a “tribute of an appreciative people to a worthy man, who [had] devoted all the energies of his life to the education and good of his race.” Alexander was destined to follow in his mentor’s footsteps.

Alexander Priestly Camphor, as he was now known, graduated from New Orleans University. He served as a professor of mathematics there from 1889 until 1893. He continued his graduate studies at Gammon Theological Seminary, Columbia University and Union Theological Seminary. He was both a scholar and a minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church.

Camphor traveled to Monrovia, Liberia, in 1897, where he was the president of the College of West Africa for a decade. In 1903, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Camphor as his vice-consul general in Monrovia, making him an American diplomat and missionary. When he returned to the states, he became president of Central Alabama College. In 1916, Camphor was elected missionary bishop of Liberia.

Camphor’s achievements coincided with a time of struggle for the Washington family. They were unable to pay their taxes, so their Burdette Street properties were seized by the state and almost sold. Washington eventually paid the debt and redeemed his property. By 1911, the Washingtons were elderly and in need of money. They sold lots 1, 2 and 3 on Burdette to Camphor and remained in possession of lots 4 and 5. Elizabeth endured the death of her husband in 1913 and soon the death of another child.

Bishop Camphor died of pneumonia on Dec. 10, 1919. In his final letter to his mother, he wrote, “If I am not restored back to health, so I can return to my work in Africa. . .I desire that my body be brought to William Chapel in New Orleans, and the Sunday School children sing Sunday School hymns and each child lay a rose on my grave.” Camphor left $1,000 to Elizabeth in his will.

Elizabeth continued to live in her Burdette Street home with her daughter Mary Washington Butler and her son-in-law. After her death, Butler and James, Major and Wheeler Washington, her surviving children, inherited the house and lots.

The elder siblings bought out Wheeler’s share. When Mary died, brothers James and Major Washington came into possession. Following James’ death in 1947, his widow sold her share to his remaining brother. Major Washington died on July 4, 1951, and his funeral was held in the ancestral home. For the first time in three-quarters of a century Burdette Street was no longer the home of the Washington family.

Camphor Hall at Dillard University is named in honor of Alexander Priestly Camphor.

Katy Morlas Shannon is the historian at Laura Plantation.