This story appeared in the April/May issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

In the midst of the Civil War, Gustave A.V. Roman was born to Louisa Edward, who also went by Louisa Parker, a biracial woman enslaved on the large sugar plantation of Roman’s grandfather, the wealthy planter and two-term Louisiana Governor André Bienvenu Roman.

Gustave’s father, Alfred Roman, was serving in the Confederate army at the time. As lieutenant colonel of the 18th Louisiana Infantry, Alfred Roman saw action at the Battle of Shiloh and later joined the staff of Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard. Alfred was aligned by marriage to two powerful Southern families: his first wife, Félicie, was the daughter of Valcour Aime, perhaps the richest Creole planter in the state, and his second wife, Sallie Rhett, was the daughter of ardent secessionist and white supremacist Robert Barnwell Rhett, a South Carolina senator.

On May 23, 1887, Gustave married Miami E. Conrad. His signature appears on the marriage certificate with a flourish. One year later, the couple’s first child was born. Over the course of five years, Gustave and his wife had four children: Romeo, Othello, Juliette and Desdemona. The children’s names suggest that Gustave was educated. He was obviously an aficionado of Shakespeare and had a flare for the dramatic. Unfortunately, the marriage did not last.

While Gustave came of age in New Orleans, Alfred Roman, who never formally acknowledged his son, was appointed judge in the city’s criminal court. By the 1890s, Gustave was struggling to support his family working as a warehouseman while his father sought to severely limit the rights of black residents throughout the state.

At the outbreak of the Spanish American War in 1898, the United States had concerns about sending troops to Cuba, where tropical diseases abounded. The Secretary of War contacted Sen. Donelson Caffery of Louisiana and asked if 6,000 recruits immune to yellow fever could be found there, to which he responded that “he could raise 20,000 such volunteers in New Orleans alone, as practically all the natives had had the fever, and all would volunteer.”

Advertisement

Gustave enlisted in the Ninth United States Volunteer Infantry, a regiment made up of men of color from Louisiana destined to serve in the Spanish American War. He was selected as one of the sergeants for M company, making him a non-commissioned officer. The regiment encamped at the Fairgrounds until Aug. 17, 1898, when they marched down Esplanade Avenue to the levee and boarded a ship called the Berlin. Crowds of Afro-Creoles gathered to watch them leave, and they were inundated with cheers and farewells.

Gustave’s war experience was markedly different from that of his Confederate father. The United States government created Gustave’s regiment because they believed men of color like him were incapable of contracting tropical diseases present in Cuba. Known as “the Immunes,” the military would soon discover that they were as subject to disease as any other group. During the six months of war, only 300 were lost in battle, while almost 3,000 deaths were due to disease. Gustave and his fellow Louisiana Creoles were on active duty in Cuba from Aug. 24, 1898, to April 25, 1899.

While Gustave served his country and sought the full rights of citizenship, his father’s widow, Sallie Rhett Roman, began a writing career based on Lost Cause nostalgia and glorification of the plantation system. She was a contributor to the Times-Democrat newspaper for two decades and also wrote fiction.

Gustave wed his second wife, Heloise Perche, at St. Augustine Catholic Church in the Tremé in 1907. He and his wife lived with her brother and sister-in-law and his daughter Desdemona at 322 N. Roman St. in the Seventh Ward. The street was named for his grandfather, the former governor. He worked as a rectifier, overseeing the refining and purification of wine. Later, he was employed as an orderly at a hospital and a custodian on an army base. He purchased a home and lot at 1936 Lesseps St. on Jan. 12, 1926, where he lived the rest of his life. The home is no longer standing.

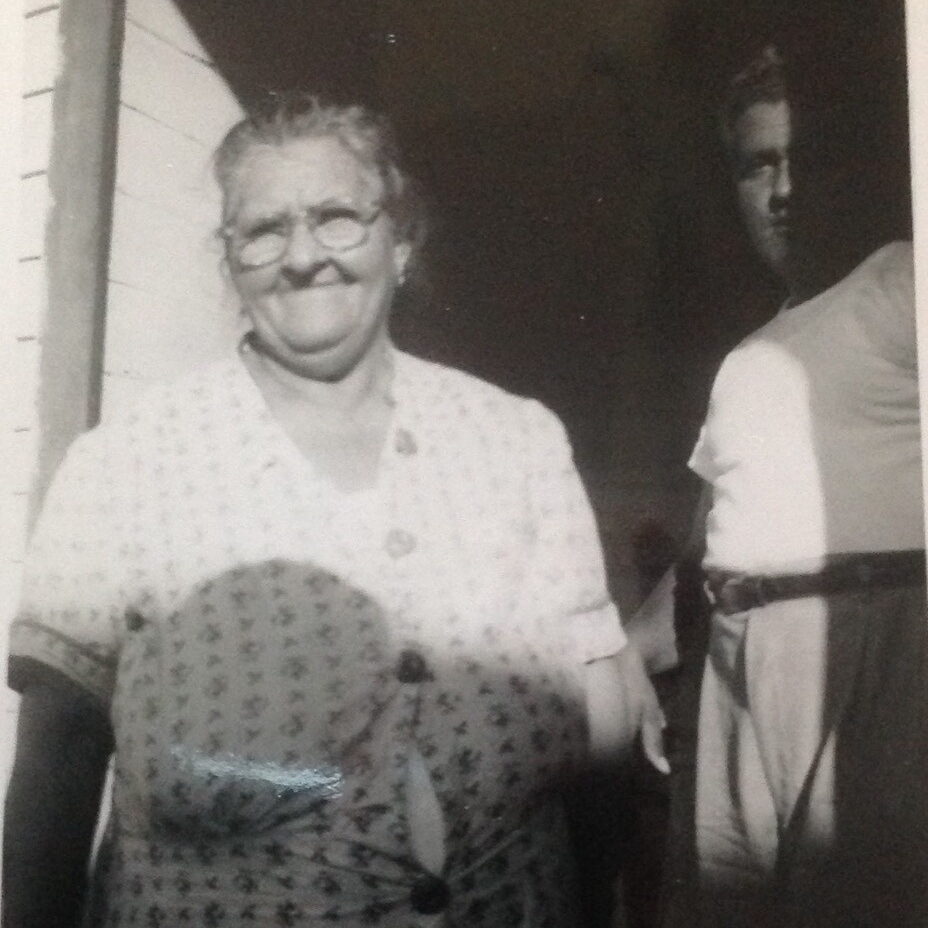

His daughter Juliette married Leon P. Honore. The couple had seven children. The oldest three, Una, Milton and Otto, participated in the Great Migration. Like many other New Orleans Creoles, they moved to California.

Two decades after his time in the army, Gustave received a pension for his service, which provided for his support in old age. He died on Feb. 20, 1953. His grave in Holt Cemetery was marked with a military headstone honoring his service.

Juliette Roman Honore, one of Gustave Roman’s children, with her son, Milton Samuel Honore Sr.

Advertisement