This story appeared in PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Every year, thousands of people fill the streets to catch a glimpse — and, if they’re lucky, a coveted coconut — from the Krewe of Zulu parade on Mardi Gras. The parade’s traditional route runs from uptown to downtown, but there are several key spots on and off the route that have played important roles in the history of the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club.

For over three decades, Clarence A. Becknell Sr. has served as the club’s historian emeritus, documenting Zulu’s evolution from its modest origins to its current status as one of the most anticipated parades on the Carnival calendar.

“We’ve come a long way to gain respectability from the community, by going out into the community and talking,” Becknell said. In addition to giving presentations on Zulu’s history at local schools, he assembles an exhibit filled with costumes, historic photographs and krewe information at Lakeside Shopping Center during Carnival season.

Zulu was formed in 1909 after a group of friends visited the Pythian Temple and saw a play about the Zulu tribe titled There Never Was and Never Will Be a King Like Me, Becknell said. Afterwards, they returned to their typical meeting place, a bar and restaurant nearby owned by John L. Metoyer, one of Zulu’s founding members.

During the impromptu meeting at Metoyer’s bar, the friends sparked the idea to organize a club inspired by the play. The founding members paraded on Mardi Gras for several years, and then formally incorporated in 1916 as the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club.

Clarence A. Becknell Sr., Zulu’s historian emeritus, has researched the organization’s history for years. He assembles a Zulu history exhibit with costumes and photos at Lakeside Shopping Center during Carnival season. Photo by Dee Allen.

In 1909, Zulu’s founding members became inspired by a play at the Pythian Temple theater about the Zulu tribe and formed the club shortly afterwards.

The Zulu parade makes a stop at the Gertrude Geddes Willis Funeral Home on Mardi Gras day each year. The funeral home was Zulu’s first sponsor in 1909.

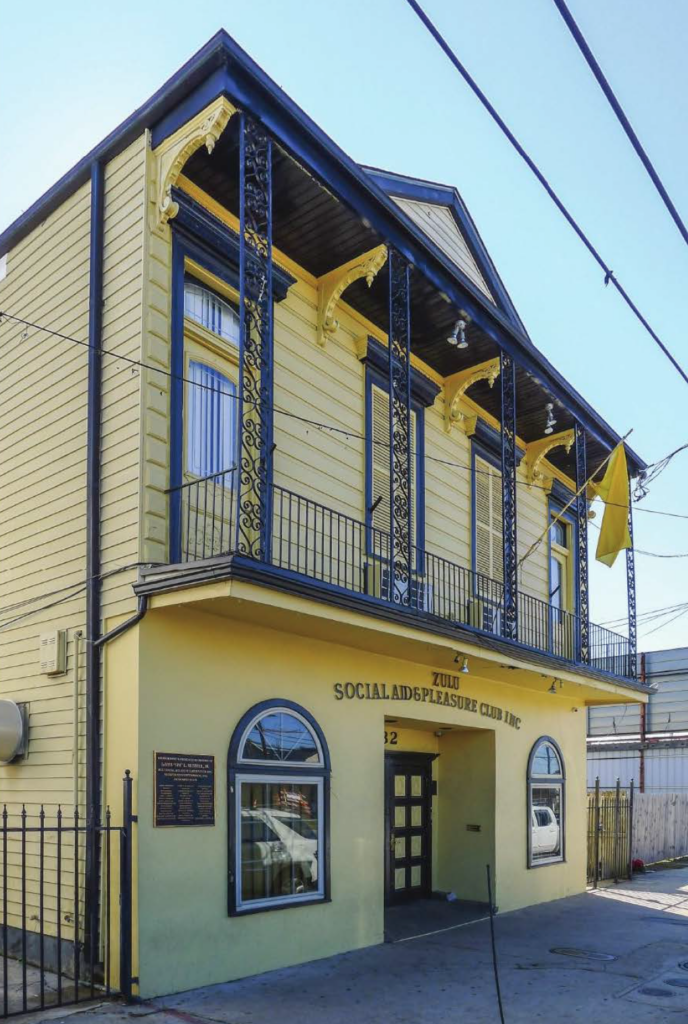

Zulu opened the doors to its current clubhouse on North Broad Street, a historic double shotgun house with a raised basement, in 1978. Photo by Stephen Kennedy.

The founders “created their own culture,” Becknell said. “One of the biggest myths that we have is that everybody ties us to Africa. But we have no ties to Africa; they just took the name from the play that they saw,” he said.

“People have been saying Zulu was formed to make fun of Rex, and that’s not true,” Becknell said, refuting another often-heard theory that Zulu was formed as a parody of Rex, the king of Carnival.

The Zulu parade is a local favorite today, but it wasn’t always allowed to travel down New Orleans’ main thoroughfares. “When it got started, it was discriminated against,” Becknell said. “We had to have our parade in the back of the neighborhoods. We weren’t allowed to go on St. Charles Avenue; we weren’t allowed to toast at Gallier Hall,” he said. The Zulu parade didn’t roll down St. Charles Avenue and Canal Street until 1969.

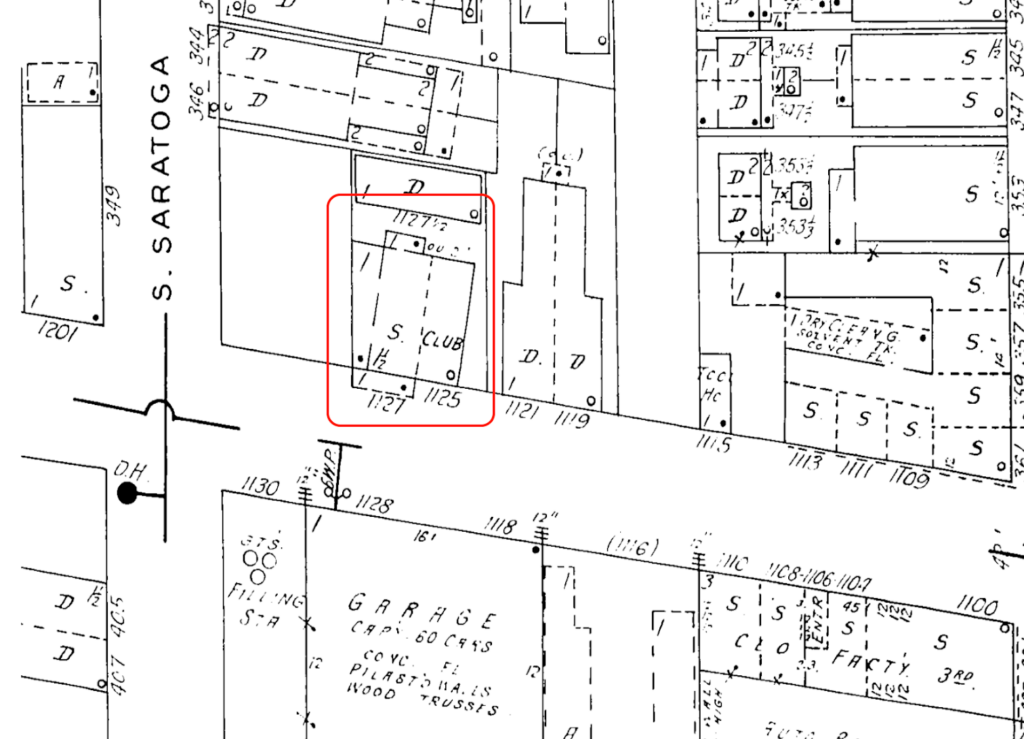

Zulu’s first clubhouse was at John Metoyer’s home at 1125 Perdido St. The building has since been demolished, and today a parking lot fills the spot where it once stood. The organization opened the doors to its current clubhouse at 732 North Broad St. in 1978. It’s a turn-of-the-20th-century bracket-style double shotgun building with a raised basement, illuminating the North Broad corridor with a bright neon sign of the Zulu crest. The club uses the building for meetings, parties and elections.

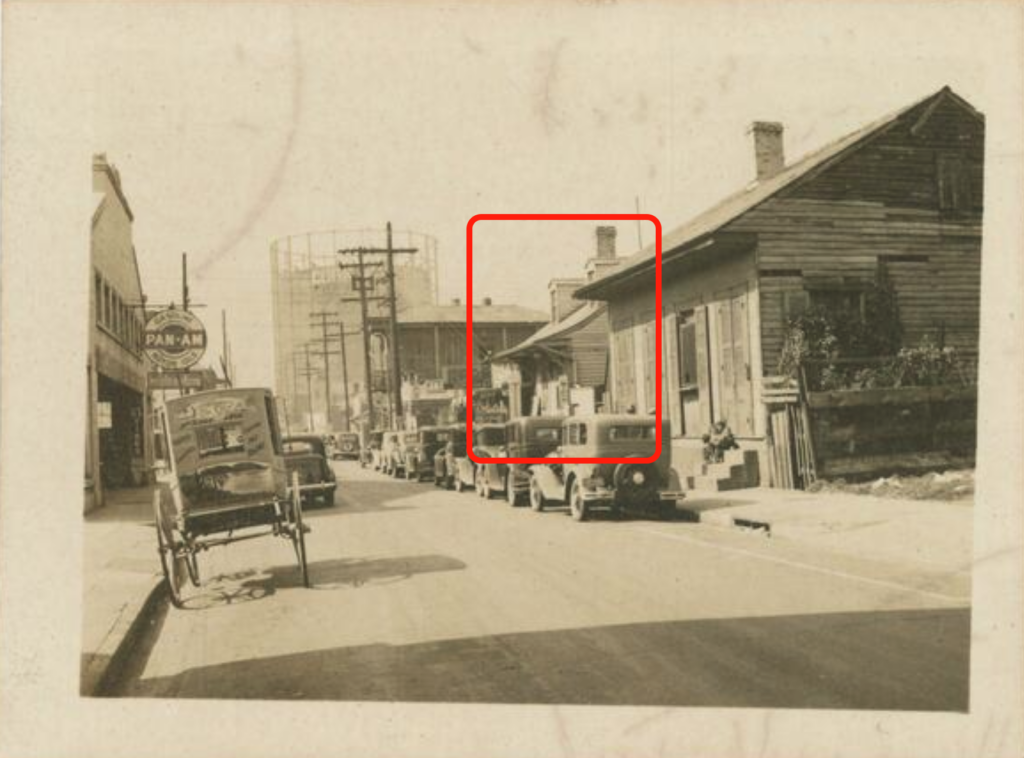

Zulu’s first clubhouse at 1125 Perdido Street, and its Mardi Gras parade Fish-fry wagon, appear in this 1939 photograph. Photo courtesy of the William Russell Jazz Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps from 1940 show Zulu’s first clubhouse at 1125 Perdido Street. The building was damaged by fire in 1943 and demolished, and a parking lot now sits in its place.

Another building that has long been an important spot for Zulu is the Gertrude Geddes Willis Funeral Home at 2128 Jackson Ave.

“They were our first sponsor back in 1909,” Becknell said. “Our first official stop is at the funeral parlor.”

Early in the organization’s history, nobody expected Zulu to be around for very long, said Becknell. One hundred years later, it’s one of the highlights of Mardi Gras, he said. “The culture is totally different from all the other parades.”

Becknell looks forward to serving as Zulu’s honorary grand marshal this year. Catch him, along with Zulu King George V. Rainey and other Zulu characters. at the parade this year on March 5.

Dee Allen is PRC’s Communications Associate and Staff Writer for Preservation in Print.