On May 15, learn more about climate resiliency at Historic Preservation in the Face of Climate Change Part II: Adapt, the second panel discussion in our 3-part “Historic Preservation in the Face of Climate Change” series. Learn more & RSVP.

This article was first published on NOLA.com|The Times-Picayune. It was reprinted in the May issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine with permission.

Each day thousands of tourists and locals pass by one of the most important pieces of architecture in this region, nestled into a block in the middle of the French Quarter. This rare building type is one of the oldest surviving houses in New Orleans. Still standing 230 years after it was rebuilt, Madame John’s Legacy offers us lessons on how to live simply and safely in an inherently resilient way, even in a hot and humid city that’s still susceptible to flooding.

Records show that the original house on the site was significantly damaged in the fire of 1788, and was quickly rebuilt in a collage of different materials, design influences and time periods. Madame John’s Legacy is typical of French Colonial houses that were inspired by Caribbean design and prevalent throughout the young city decades earlier. However, it was rebuilt while New Orleans was under Spanish rule, and was constructed with some materials salvaged from the destroyed structure. It’s also a truly Creole building, constructed by an American builder for a Spanish owner while adapting French and Caribbean architecture to suit the New Orleans climate.

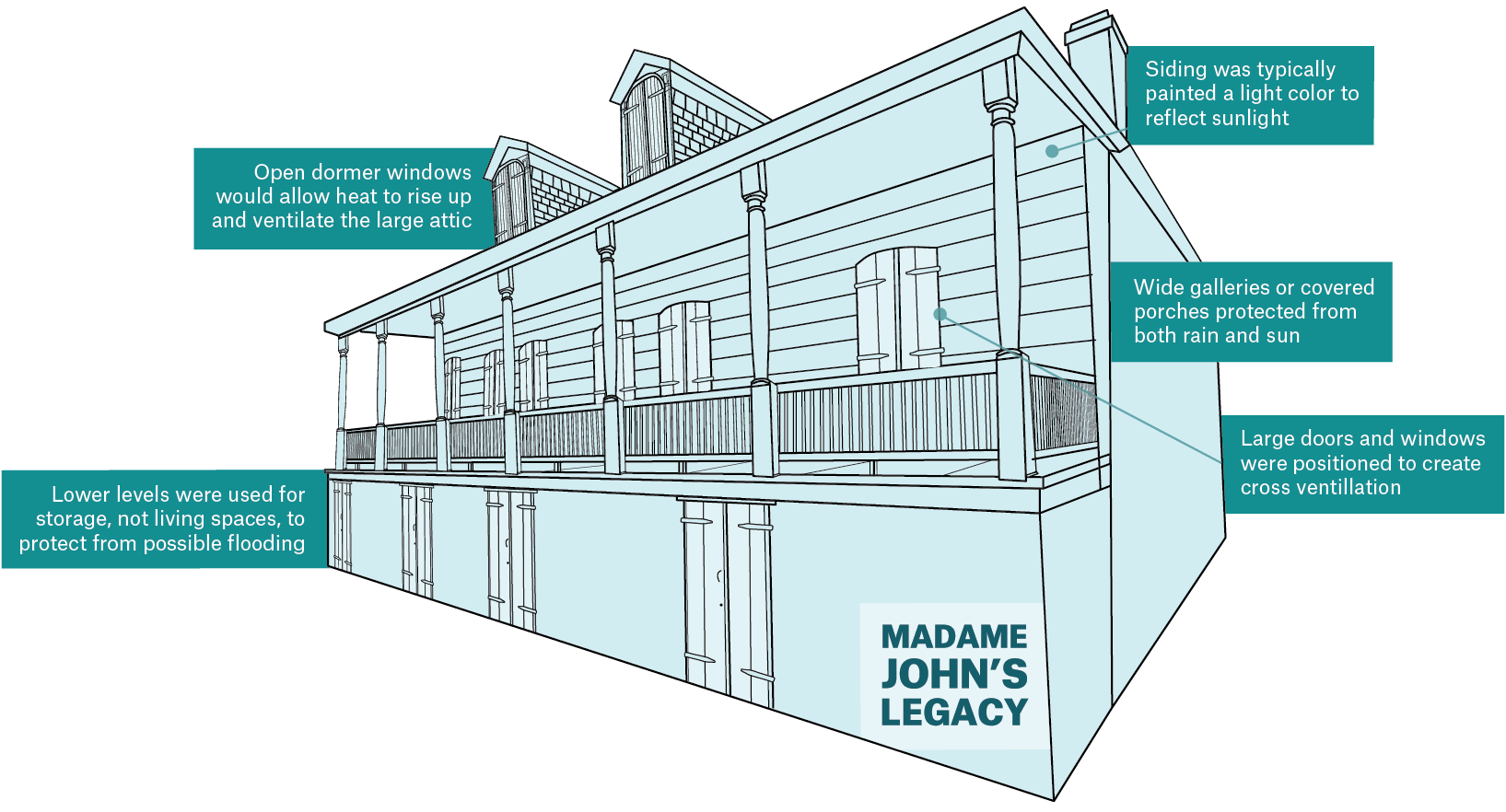

Long before the current drainage system of pipes, canals and pumping stations, New Orleanians designed buildings to live with water. In case of flooding, the lower level was used for storage, not living spaces, and was built with water-resistant materials of solid brick covered in painted stucco. The architecture was designed to get wet and then dry out — over and over. Today, we would call this approach “wet flood-proofing.”

Advertisement

Adapted to the local climate, these design strategies are called “passive” or “bioclimatic,” and were the norm before modern, energy-intensive air conditioning and heating systems. At 8 feet above the street, the house’s main level also is elevated to catch breezes, with large doors and windows positioned to create cross ventilation and let in daylight, protected by wood shutters during storms. Steep roof pitches shed rain, and wide galleries, or covered porches, on the front and back protect from both rain and hot sun.

The architecture of the house also embedded effective strategies to deal with heat. Walls constructed of soft brick between wood posts were covered in wooden boards to resist blowing rain. This siding was painted a light color, as it is today, to reflect the sun. Small dormers peek out of the hipped roof to ventilate the large attic, which was used for storage and features impressive exposed timber framing. The attic also works as an insulating air space. During the summer, open dormer windows would let heat rise up and out from the living spaces below, and in the winter, the dormer windows would stay closed to keep the warmth in.

An official description of the property from 1788 described the simple architecture as a “pavilion raised on a brick wall.” After another large fire in 1794, the Spanish government enacted building codes that required fireproof construction of solid masonry in the rebuilding effort. This meant that buildings like Madame John’s Legacy, a freestanding structure with a wood-framed upper story, were prohibited for new construction.

Madame John’s Legacy is a rare surviving remnant of our early city, helping us imagine how colonial settlers adapted to the challenges of our place.

The next time you’re walking around the French Quarter, stop in front of 632 Dumaine St. and admire this simple, yet sophisticated, climate-responsive and flood-resistant historic architecture. It might inspire ideas for living in a smarter, more resilient way today.

Operated by the Louisiana State Museum, Madame John’s Legacy is a historic house museum. It is currently closed for restoration. Visit Louisianastatemuseum.org for updates.

Thom Smith is an architect and urban designer with Waggonner & Ball and part of the firm’s resilience planning team. He also is a member of the Preservation Resource Center Board of Directors.

Historic Preservation in the Face of Climate Change Part II: Adapt

May 15, 6-7:30 PM • New Canal Lighthouse, 8001 Lakeshore Drive

The second panel discussion in the 3-part Historic Preservation & Climate Change series will discuss the balance between authenticity and long-term survival of historic spaces. Learn more & RSVP!

Advertisements