This story appeared in the April issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

I’m a Preservationist

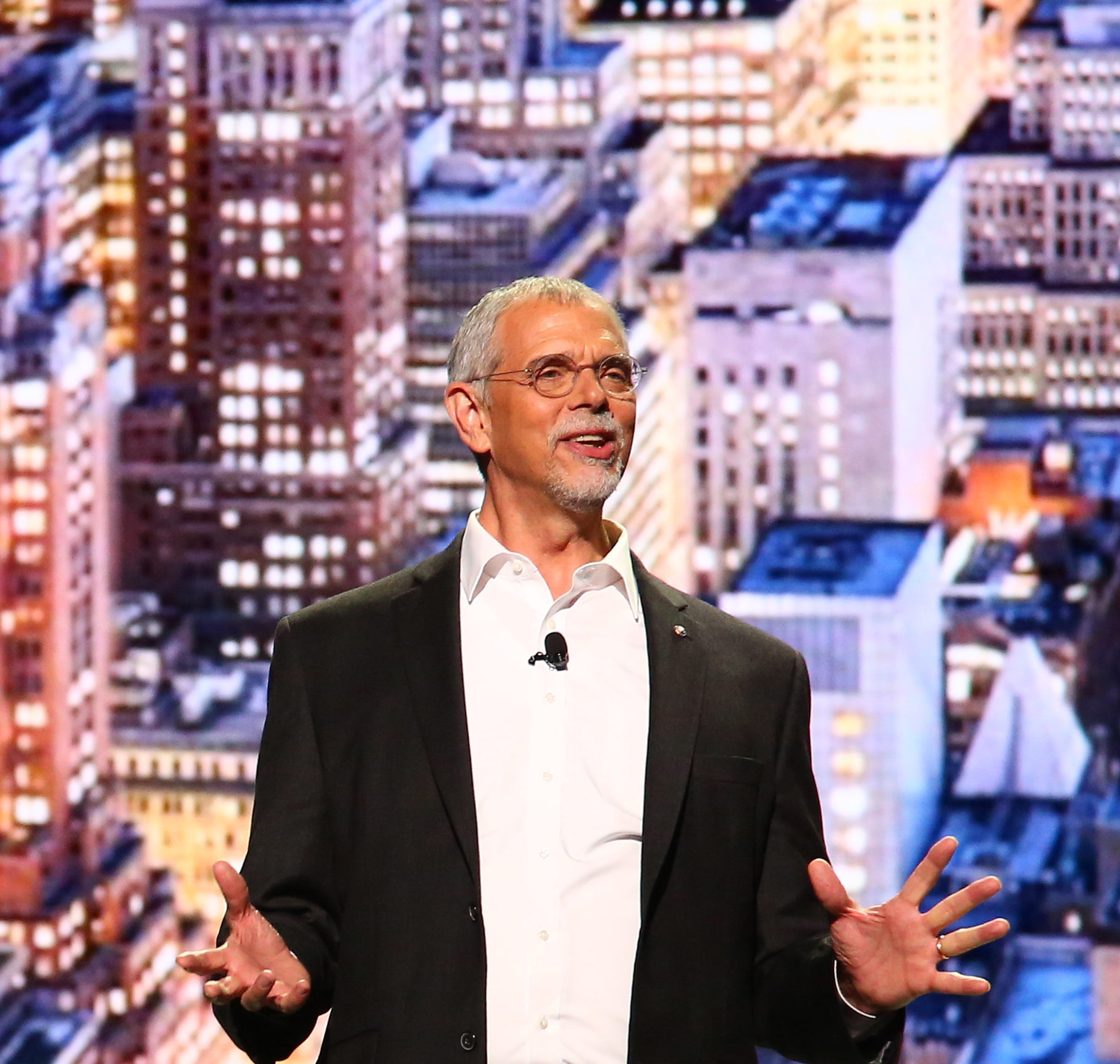

J. David Waggonner III – Principal, Waggonner & Ball Architecture and Environment

Your firm led the development of the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. It’s been seven years since the plan was unveiled. Do you think New Orleans has made progress in its approach to “living with water”?

This is a difficult problem. We have made progress, but we need confidence in our direction as well as more urgency about this preferred alternative future. As we see again now, neither the environment nor the political economy is static. The things we take for granted can change quickly. We need continuously to define the problem in immediate terms and set and meet short-term goals, like getting projects up and running, and rooted in the ground. We need more positive, real-world examples that people can see and learn from: local victories to sustain systemic change. This needs to become a competition to the top. We cannot let the gravity of events drag us under.

Living with water is a three-part equation in New Orleans: dealing with rain, managing groundwater and subsidence, and improving quality of life through water. Quality of life includes aspects of revenue. To become a sustainable city, we need to increase our value, and demonstrate our value, to ourselves and the country. Someone has to pay to build, to maintain. One way we can do that is just to make water more visible.

New Orleans was the first place to hold the Dutch Dialogues, in which urban design and water experts reimagined how the “fundamental qualities of water and the landscape can reshape the way we live in an urban delta.” They’ve since been held in Norfolk, Va., and Charleston, S.C. What can we still learn from other places and what can they learn from us?

Lessons from Louisiana are invaluable for other waterfront cities. We are constantly reminded of the uniqueness of our city — of its identity, the remarkable influence of nature and the land and water around us on our innate culture — but our issues are not entirely unique. More than science-based research and technical solutions, other cities find our way of working to be transformative. People understand the importance of shared values and community ties. We’ve been invited to help other places get organized around their core challenges, help them get oriented around the physical landscape rather than political boundaries or the regulatory framework. And we’ve shown others the incredible value not only of an interdisciplinary approach to design but also of inclusivity and collaboration.

Working elsewhere gives one the opportunity to look in the mirror and see one’s home with fresh eyes. We take great inspiration from elsewhere, both from the talent and energy of those with whom we work, and from the natural beauty of a place like the Charleston Lowcountry. Charleston also reminds us of the importance of scale, and how to uncover opportunities within and between urban watersheds. Most places don’t have the stark boundaries that we do, inside and outside the levees, and we do well to remember the importance of multiple lines of defense, of natural gradients and flows.

Advertisement

Waggonner & Ball is the architect of the new Mirabeau Water Garden project within the Gentilly Resilience District. The garden will store more than 10 million gallons of diverted stormwater and serve as an educational and recreational amenity for water management. How is that project coming along?

We’re ready for the Water Garden to break ground, and we’re encouraged that the city is fully committed to getting it built and is now releasing the plans for bid. The project is rich on many levels: as functional blue-green infrastructure, as a neighborhood park, as a deeply spiritual place. With this land, the Congregation of St. Joseph is making an important gift to our city. Mirabeau is a place we as New Orleanians will be able to connect to our ecological roots. So many aspects of the city, our geology and infrastructure and people and environment, come together on that site, I think it will be a transformational project for the city. Phase two of the project is a watercourse, more plantings and pavilions for environmental education near where the Sisters had their home. This is funded separately through the National Disaster Resilience grant.

Waggonner & Ball was the architect for The Historic New Orleans Collection’s beautiful restoration of the historic Seignouret-Brulatour House and construction of its new contemporary exhibition wing. The project received LEED Silver certification, making it one of the oldest LEED-certified building in the country and the first in the French Quarter. The renovation and new construction are both very sensitive to the historic neighborhood. Did you have any special challenges bringing an 1816 building up to LEED standards?

The client was receptive to LEED from the very beginning of design. The goal was LEED certified but we were able to push further to Silver. So much of LEED owes to energy performance, it made sense that the LEED coordinator was the same consultant who designed mechanical and electrical systems for the project. While we were able to add insulation at the attic, the existing brick walls and single-glazed wood windows presented a challenge to achieving an energy-efficient envelope. This was partially offset by the new addition, where exterior walls were energy efficient and glazing was minimized and north-facing, both to reduce sunlight on exhibits and limit heat gain.

In some ways, the site was constrained, since the original 1816 figure/ground was maintained, but in others it was quite generous, giving us rare opportunities. Demolition of less significant buildings in the center of the block — formerly WDSU studios and a portion of a garage — allowed for significant new construction, notably four large galleries. Other portions of THNOC’s property in that block gave critical space for staging during construction and, in the completed building, a great deal of concealed space for large scale secure deliveries, emergency generator and two trailer-size stormwater storage tanks (17,000 gallons total) that relieve city drainage system during peak rain events.

LEED awards less credit than you would think — one point — for saving an old building, but there are always inherent efficiencies to restoring older structures with noble materials, not to mention preserving the unique stories they have to tell. We salvaged existing pine flooring and reused it at some public portions of the entresol, and supplemented it with much more antique pine flooring salvaged elsewhere in the area. An elder craftsman restored an unusual heavy timber spiral staircase, which with small moves like adding bronze railings, could be used for required exiting without compromising original details or character, or building more than one new stair. Removed paint layers exposed granite façade elements. With Cypress Building Conservation’s research of samples taken on site, we specified integrally colored lime plaster wall finishes that are closer to the historical formula than the Vieux Carre mix, which still contains some Portland cement, and whose hardness is not completely compatible with underlying soft historical bricks. The courtyard well and brick paving of the 19th-century habitation were restored, and without waste now show both history and hydrology.

As you work with building owners and homeowners across the city, how invested are residents in the new way of thinking about water and resilience? Do we have community “buy-in” for the idea of storing water and living with water here?

While individuals can only do so much, it is essential that we each appreciate we have a role to play. We also need to inspire new ways of building and managing the big system. Political buy-in usually starts with citizens, but we’ve seen the city, as well as the state with its Louisiana SAFE program, take positive steps. The Gentilly Resilience District, of which Mirabeau is a part, is a prototype for integrated district-scale water management. We are now working with the city on water storage projects in City Park, and, of course, the updated CZO (Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance) now includes water storage requirements for new construction.

The business community also now recognizes the issues and is taking up the charge. We are pursuing water projects with support from the Business Council and Downtown Development District. Our streets and public spaces are seen differently through the water management lens. The Water Collaborative is coming into its own as an organization. Ripple Effect is educating our children in public schools about water and design.

Finally, design community buy-in is also critical, including our engineering partners in the public and private sector. We need to be the loudest advocates for change, backed up by new ideas. It’s not only about what’s in the Water Plan. There are many projects out there to discover and create. We’re all about building America’s Water City.

Advertisements