From roughly 1905-1914, The Daily-Picayune published a Sunday illustrated magazine on smooth finish “calendar” paper. These supplements measured roughly 10 by 15 inches in size and were issued as 20-page segments that contained a mix of literature, including syndicated short stories and serials, as well as features on travel. Additional photo pages and centerfold spreads — exemplars of the illustrious interaction between photography and illustration styles of the time — also filled the pages. For reasons unknown, these works from the Golden Age of Illustration and many other serials were completely left out of the microfilm archives altogether; but miraculously, dozens upon dozens of originals have survived in the Nola DNA collection, and beg for further attention and exhibition.

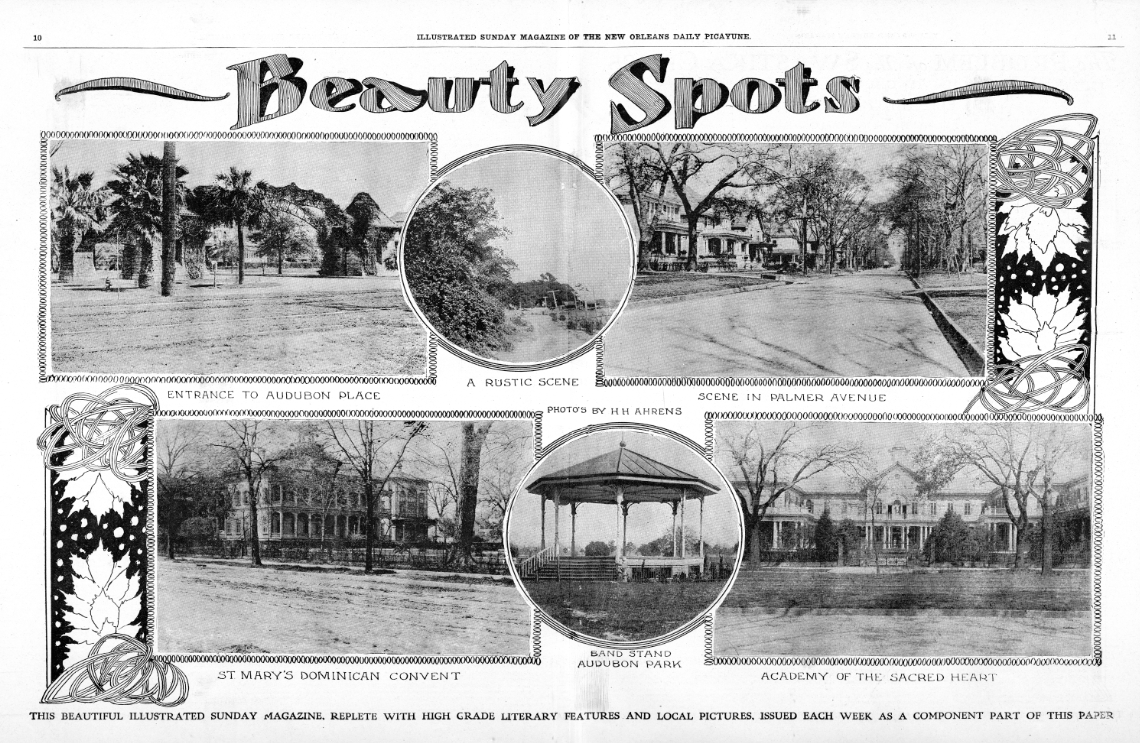

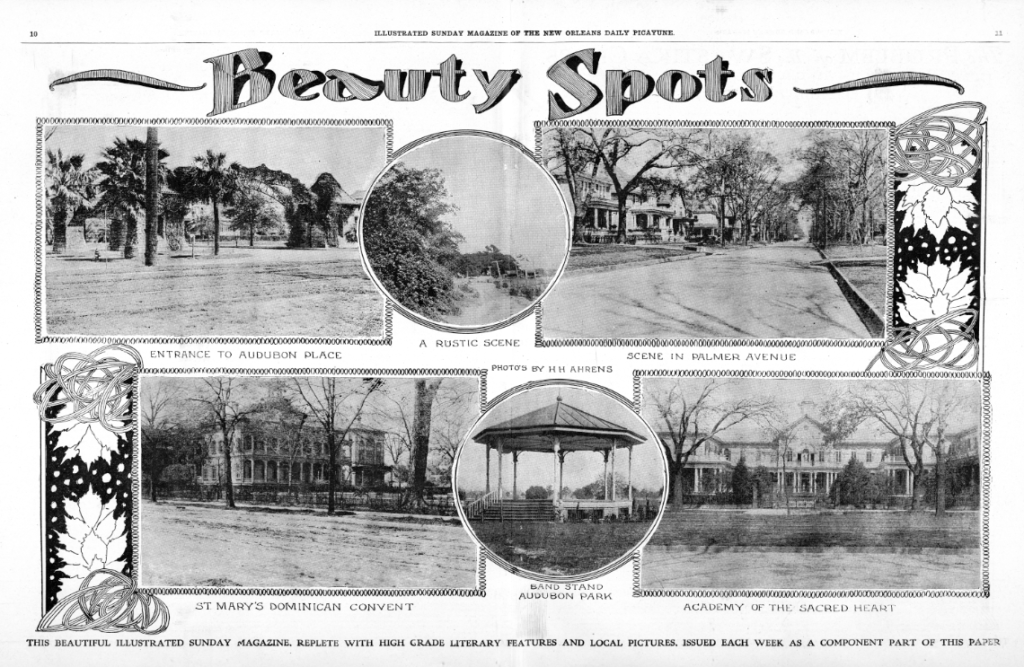

One particular centerfold from the June 19, 1910 issue caught my attention with its hand-illustrated shadow-backed title text “Beauty Spots,” appearing to pop off the page with three-dimensionality. The content of the photo spread is quite simple and balanced: it presents specific places worthy of adminration, like the entrance to Audubon Place and a bandstand in Audubon Park, but also less specific and vague locations that could be almost anywhere, such as “a rustic scene” presented in the top center circle. This and other centerfold spreads seem directly related to the process and philosophy of “placemaking” — a distinctly modern concept advocated by people such as writer-activist Jane Jacobs and urbanist Wiliam Whythe.

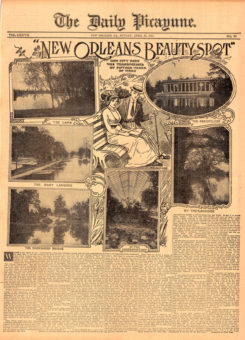

But what if this idea of placemaking had been there far longer in the hearts and minds of city-dwellers who sought for more access to public spaces and had their eyes set on more of these “beauty spots?” This question led me to yet another section from just a few years later — April 27, 1913, to be exact — with an occurrence of the same phraseology: “New Orleans Beauty Spot – How City Park was transformed by fifteen years of work.” While digging deeper I found the exact evidence I was looking for to substantiate my claim: By the late 19th and early 20th century, New Orleans’ would-be preservationists had intentions of actually engineering particular places with placemaking distinctly in mind.

According to the piece, since 1891 the city had been holding a City Park Festival and yet by 1913, with a predicted 20,000 attendees to the event, the organizers were most worried about one thing: getting all those people transported safely to and from the park itself, via modern street cars, new model automobiles or by horse and carriage. But the work the park committee had been doing for 15 years or more was intentional in reinventing its use for the people of the city, stating that not long before, “the park itself was little more than wilderness. Weeds as high as telephone poles … the stately oaks – now the crowning beauty of the park – (once) stood in desolate loneliness.”

The commissioners of City Park were determined to follow the advice of a festival guest speaker from 15 years earlier, only named in the article as “a certain newspaper man.” He challenged them by saying this: “Create the demand and all other things will follow. Improve the park to such an extent that the people will want to visit it, and you will have no transportation troubles.” Their work paid off with beautifying the park and they even raised the value of the surrounding property: “Where once there had been dairies and cow pastures, handsome homes sprang into existence.” So it was in the intention to participate in their very own version of placemaking some 60 years before the term itself was coined that City Park leaders created the beloved municipal park enjoyed by so many today. They listened to their community, were conscious of pedestrian interaction, involved a concerted group effort, acted on observations, had vision and patience — and it is clear that these tenets still hold true for how City Park upholds this legacy.

The commissioners of City Park were determined to follow the advice of a festival guest speaker from 15 years earlier, only named in the article as “a certain newspaper man.” He challenged them by saying this: “Create the demand and all other things will follow. Improve the park to such an extent that the people will want to visit it, and you will have no transportation troubles.” Their work paid off with beautifying the park and they even raised the value of the surrounding property: “Where once there had been dairies and cow pastures, handsome homes sprang into existence.” So it was in the intention to participate in their very own version of placemaking some 60 years before the term itself was coined that City Park leaders created the beloved municipal park enjoyed by so many today. They listened to their community, were conscious of pedestrian interaction, involved a concerted group effort, acted on observations, had vision and patience — and it is clear that these tenets still hold true for how City Park upholds this legacy.

And so, dear reader, I ask: consider not just only your favorite “beauty spot” but also what neglected site you might dedicate a little extra time and labor to, in making it a special place to share and enjoy with others this year and beyond.

Above: Illustrated Sunday Magazine of the Daily Picayune, June 19, 1910 – Pgs. 10-11. Previous: The Daily Picayune, Sunday, April 27, 1913.

is an original archive of over 30,000 historic New Orleans newspapers from 1888-1929, delivering history on demand through clever curation, graphics and print. Curator Joseph Makkos is using materials from the archive to write this special series for Preservation in Print in celebration of the Tricentennial.