This story appeared in the March issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

“Victorian,” in the strictest sense, refers to the years of Queen Victoria’s lengthy reign over the United Kingdom, 1837 to 1901. By extension, it implies the society as well as mores and tastes of that period. In New Orleans and elsewhere, however, the adjective usually describes architecture, particularly the styles of the late I 800s. Their appearance, and eventual decline, may be understood in the context of the evolving philosophies and counter-reactions regarding the relationship between people and buildings; New Orleans over the course of its three centuries offers a good case study.

Throughout the 1700s, structures in New Orleans were generally vernacular, created by local architect-builders (“housewrights”) who adapted traditions from France and French Canada, the Caribbean, West Africa and Spain to the deltaic conditions of subtropical Louisiana and urban conditions of La Nouvelle Orleans and Nueva Orleans. The architecture was known broadly as Creole, and it was fundamentally functional.

During the early I 800s, New Orleans politically Americanized, its population diversified and its building arts reflected the new order. Professional architects from out-of-town pushed aside old Creole customs in favor of new forms reflecting Enlightenment philosophies inspired by classical antiquity. The dignified architecture that resulted came to be known as Classical or Neoclassical, most prominently Greek Revival, and it heralded rationalism, order and a genteel aristocracy.

Too much order and aristocracy stirred a counter-reaction, one that valued emotionality, beauty and the spirit of the individual. That movement, called Romanticism, was paralleled in the United States by the budding frontier ethos of individualism and self-sufficiency, and the economic rise and political empowerment of the “common man:’ By the 1840s and 1850s, majestic Greek temples and townhouses started to look dour and passe. Architects rediscovered more recent Medieval and Renaissance influences and breathed new Romanticist life into them – and found plenty of nouveau-riche clients eager to display their wealth through houses so designed.

What resulted in the early Victorian years were more luxurious aesthetics primarily of the Italianate order. The exuberance flourished later in the Victorian period, and it’s probably the sundry panaches from those years, l 870s- l 900s, that most New Orleanians picture when they think of Victorian architecture. Among those styles were Stick, with its emphasis on wooden detailing (“stick work”) and its variants, Queen Anne, distinctive for its towers and turrets, and Eastlake, with its panoply of brackets, quoins, railings, spindles and skin-like shingling. There was also stony Romanesque with its stout rounded archways; francophile Second Empire and its mansard roofs; imposing Gothic with its pointed arches; Tudor with its nostalgic rusticity; and a flamboyant expression of classical and Renaissance motifs known as Beaux-Arts.

Architecture blossomed in this era, almost literally, with florid embellishments and cornucopias of fruit bandied all over exteriors and interiors. It was not a time for understatement.

The trend did have some democratizing aspects. Mass production had made woodworking cheap, which enabled builders and owners of otherwise humble houses to spruce them up into charming mini-manses: thus our thousands of gingerbread-encrusted Victorian Italianate shotgun houses. Similarly, homes with modest adornment were featured in pattern books (“catalog houses”) and mass-constructed for middle class families, creating appealing neighborhoods such as today’s Bayou St. John and Mid-City. Algiers Point particularly abounds in lateVictorian homes because a terrible fire laid waste to its IO core blocks at precisely the time – 1895 – when these styles peaked in popularity for new construction.

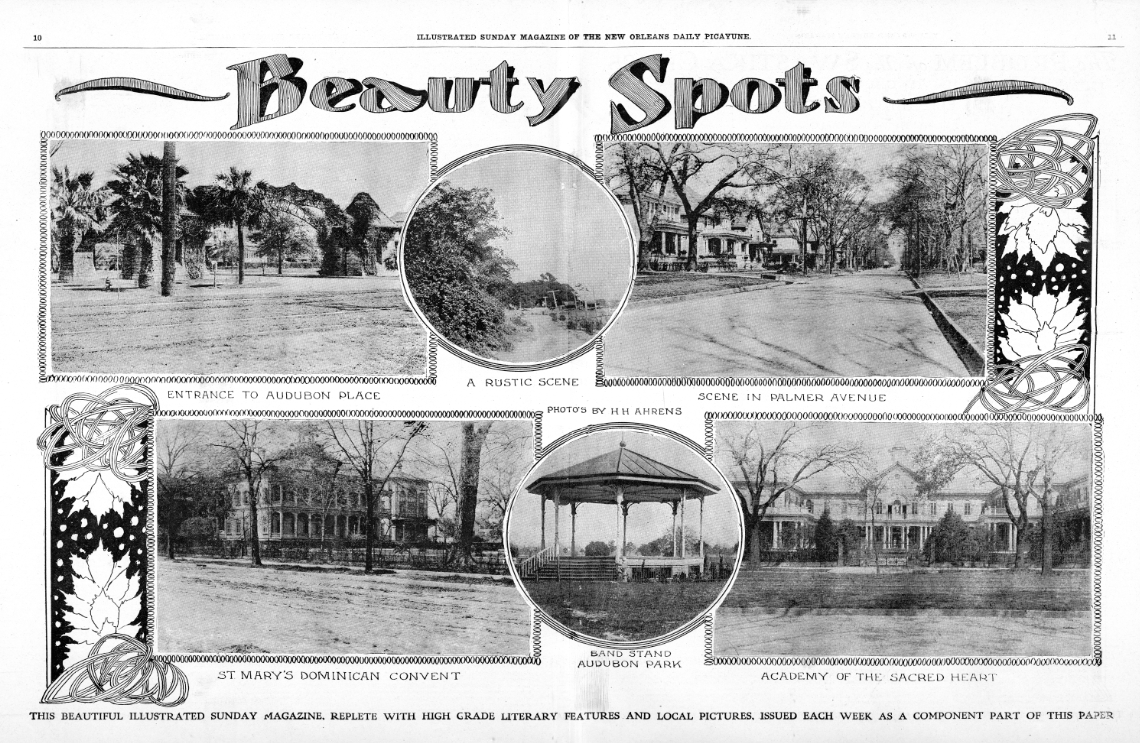

It was the housing stock built for the upper class which would become the iconic specimens of late-Victorian residential architecture: huge, vertically massed frame houses with busy roofs, deep-set wrap-around porches and detailing galore. Architects peddling such blueprints found the perfect clientele in uptown neighborhoods, which boomed in the years following the 1885 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial in present-day Audubon Park. “The present season in New Orleans has been one of exceeding activity in … building and improvements;’ reported the Daily Picayune in an 1888 real estate article subtitled “The Sound of the Saw and Hammer is Heard in the Land:’ “The architecture;’ noted the journalist, “is much more elaborate and original than formerly, the prevailing style for cot1ages and residences being the Queen Anne, the Eastlake, old colonial, etc.(,) all of which will prove to be ornaments to the city.”

-

The New Orleans Cotton Exchange was built in 1871 in Victorian styles including Second Empire and Italian Renaissance. The building was razed in 1920. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

-

Canal Street’s late Victorian architecture, seen here aroung 1890. Photo by William Henry Jackson and courtesy Library of Congress.

-

The Mercier Building, built 1887 and home to original Maison Blanche, on Canal and Dauphine Streets, was razed in 1907. Photo courtesy Corbis.

Victorian ornamentation was also applied to new commercial and institutional buildings, causing parts of downtown to shed their antebellum scale and distinction for the latest look appearing in other American cities. The Mercier Building on Canal Street at Dauphine Street (1887, home to the original Maison Blanche) and its rival Godchaux’s (1899) on Canal on Chartres Street, visually splendid as they were, nevertheless could be picked up and dropped seamlessly into Cincinnati or Boston or Detroit. Most New Orleanians did not see this as a problem; they saw it as progress.

A number of factors drove late-Victorian exorbitance. Raw materials such as lumber, quarried stone, and coal for calefaction were inexpensive, given the largely unregulated extraction of natural resources at this time. Mechanized mills and expanded rail lines lowered production and transportation costs. Skilled labor and domestic help were cheap; federal income tax did not yet exist; and real estate taxes were minimal, all of which freed up household income to sink into the house. There were no zoning regulations limiting size or style, and because municipal water, gas and electrical services were either nonexistent or nascent, utility bills were hardly an issue.

Furthermore, this was the Gilded Age, when industry and economic expansion swelled the ranks of the upper class and yielded a new American elite. Unlike its counterparts from earlier times, this generation proudly displayed its wealth, and there was no better way to do so than one’s residence. For a wealthy family in the late 1800s, there was no reason not to build big and grand. Motifs got mixed and matched ad nauseam, and home sizes grew ever larger, as if to say more, is always better and too much is never enough.

And that’s what drove the counter-reaction.

It began in England in the 1880s and took root in the United States by the early 1900s. Its philosophy was, by its very nature, low-key and understated, eschewing machine production and frivolous detailing in favor of natural, hand-crafted simplicity. The movement came to be known as Arts and Crafts, and at its core, it held that less was more, and too much was not only more than enough, it was vulgar.

To be sure, the extravagance continued even after Queen Victoria died in 190 I and Prince Edward ascended to the throne. The Modernist movement, emerging since the 1870s and intensifying after World War I, probably played a greater role in killing Victorian and Edwardian architecture, as did the rising costs of owning a big drafty wooden house. The shift in taste got underway locally around 1910, when architects and homebuyers found refreshing charm in simpler, earthier designs known as Craftsman. In part the trend emanated not from the Northeast or England, nor from medieval or ancient precedents, but rather from the contemporary West Coast: enter the California Bungalow.

Yet late-Victorian architecture left an indelible impression in the collective aesthetic, becoming almost the archetype, in many Americans’ minds, of what beautiful houses and idealized domesticity are “supposed” to look like. Christmas cards, children’s books, and toys such as doll houses and model train layouts feature Victorian houses with striking regularity, and cinema has used them as props to evoke everything from hope (Tt’s a Wonderful Life) to horror (Psycho).

The Victorian period left a considerable structural mark on the New Orleans cityscape. Despite the fame of the city’s Creole legacy, far more extant buildings date to the late 1800s than the 1700s and early 1800s combined, and late-Victorian stylistic specimens substantially outnumber those of Creole or Greek. The aesthetics of that era also live on in the fa,;ades of new residential construction. A study I conducted of hundreds of homes built after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 revealed that nearly three out of every four fa,;ades had a historical pastiche – and of those, most paid homage, either partly or largely, to Late Victorian tastes.

An earlier version of this article appeared in Richard Campanella’s “Cityscapes” column.

-

Details of an 1896 Queen Anne house on Exposition Boulevard.

-

A Queen Anne house on Exposition Boulevard.

-

The upper floor of the Parkview Guest House, originally built 1896, on St. Charlesn Avenue and Walnut Street.

-

The Round Table Club House, built in 1896, on St Charles and Exposition Avenues.

-

A late Victorian house in Algiers. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, courtesy Library of Congress.

-

Late Victorian detailing on a row of Garden District homes.

-

The porch of the Parkview Guest House, built 1896, on St. Charles Avenue and Walnut Street. Photos by Richard Campanella.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture is the author of “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma,” “Geographies of New Orleans” and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.