This story is a tricentennial feature from the March issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Trauma Motivates. Unlike incremental setbacks, which can pass unnoticed, losses that are sudden and dramatic have the power to draw attention and galvanize response.

A century ago, three traumatic losses in the French Quarter caught the attention of civically engaged New Orleanians, and, in time, would spur them into action. What resulted was the articulation of the preservationist argument, followed by the organization of policy action. It would take the better part of the next half-century for the local preservation movement to gain citywide momentum, but it probably would have started later and taken longer were it not for the loss of over four acres of some of the city’s very best historical architecture.

The first episode began as a well-intended initiative to reinvest in the urban core, by erecting a new state courthouse and a federal post office on either side of Canal Street. The aging Cabildo was serving unsatisfactorily as a courthouse up to this point, and in 1895, the city proposed razing the old Spanish-era building, as well as the Presbytère, and replacing them with modern court facilities. In an early preservationist expression, a public outcry arose; the city relented, and the two landmarks were later converted to museums. Instead, a new courthouse as well as the post office would be built in a new location. Partisans for the Second District (the French Quarter) and First District (today’s CBD) advocated to land either project — or both — on their side of Canal Street, and two commissions were formed to decide.

The Courthouse Commission eventually selected 400 Royal St. for the state supreme court. Demolitions of an entire square of graceful century-old Creole townhouses, including the culminating section of Exchange Alley, began on June 1, 1903. Many who viewed the French Quarter as a dirty slum felt such modernization was long overdue, but others were dismayed by the sheer scale of the destruction, which dragged on for years. The Daily Picayune gave voice to both stances, lamenting the loss of “one of the most historic sites in New Orleans, [in] the very heart of the vieux carré[,] and though still palpitant with memories of pioneer bravery and colonial splendor, it must be torn to pieces that progress may continue its onward march.”

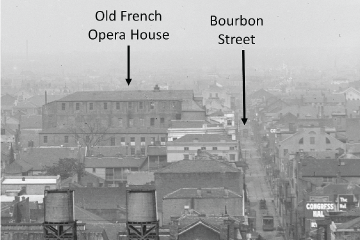

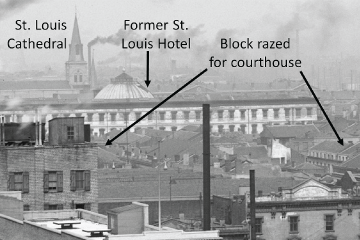

1900 rooftop view of the three major losses of the upper French Quarter, 1903-1919. Graphic by Richard Campanella based on a Library of Congress image.

The Louisiana State Supreme Court Building, a Beaux Arts behemoth out of scale and style with its surroundings, opened in 1910. As for the federal project, the Post Office Commission selected 600 Camp St. for its site, across from Lafayette Square, and more demolitions of prominent historic buildings followed. The Italian Renaissance-style complex opened in 1915, and today it is home to the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

That same year, a fierce hurricane struck the city, toppling 11 church steeples, destroying Horticultural Hall, and wrecking Leland University on St. Charles Avenue. In the French Quarter, across from the new courthouse, the Great Storm of 1915 also damaged the landmark dome of the famed former St. Louis Exchange Hotel, one of the most important buildings from the antebellum era. Originally designed by J. N. B de Pouilly and opened in 1838, the St. Louis would become, according to the Daily Picayune, “the pride of New Orleans[,] the wonder and admiration of strangers, the most gorgeous edifice in the Union.” A fire in February 1840 completely destroyed the hotel, but owners speedily rebuilt, this time with a fire-resistant lightweight rotunda. “We rejoice in seeing its lofty dome soaring again to the sky,” beamed the Picayune in May 1841, “once more a proud architectural boast of New Orleans.” For the next 20 years, the St. Louis would form the nucleus of Creole society and commerce — as well as a busy auction site, including the site of enslaved people, beneath the 88-foot-high dome surrounded by towering Tuscan columns.

The hotel closed during the Civil War, after which the state purchased the building for use as the Louisiana State Capitol. In the 1890s it reopened as the Hotel Royal, but lacking the panache of earlier times, patronage declined and the lodge folded. The building soon found itself, according to a 1906 retrospective, in a state of “silence, neglect, emptiness and gloom,” occupied only by vagrants and the occasional stray horse. After further damage in 1915, the building was sold to the Samuel House Wrecking Company, which proceeded to dismantle it by early 1916. The site would remain a weedy salvage yard for decades.

Three years later, on December 4, 1919, a fire broke out in one of the most beloved and culturally significant landmarks in the city. Designed by Gallier and Esterbrook and built on the corner of Bourbon and Toulouse Streets, the French Opera House opened with a triumphant performance of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell on December 1, 1859. “Superb… magnificent… spacious and commodious,” raved the Picayune of the gleaming white Neoclassical hall, “a spectacle…richly worth viewing [at] a scale of great elegance.” The Civil War and its aftermath made for rocky times for the venue, yet it persevered, featuring performers from France and throughout the Francophone world. Creoles particularly adored the place; local children would attend Sunday matinees for 25 cents to take in French-language entertainment. One youth, Mildred Masson, described many years later how the grand edifice was “my second home…I practically lived there[,] three nights a week, and then we had the matinee on Sunday.”

It all ended in that late-night blaze. By dawn, wrote one local journalist, “[t]he high-piled debris, the shattered remnants [and] wreathing smoke, all made the historic site resemble a bombarded cathedral town.” New Orleanians openly mourned the trauma — and this time, the sense of loss was widespread. The Old French Opera House, wrote one editorialist in the Times- Picayune, was “the one institution of the city, above all which gave to New Orleans a note of distinction, [as an] anchor of the old-world character of our municipality…without [which] will be the gravest danger of our drifting into Middle-Western commonplacity.” So intrinsic was the theater to local culture that some pondered whether its loss would “sound the death knell of that entire quarter of the city, with its odd customs that charm the stranger.”

And it might have, had not citizens stepped up from the ashes of the Old French Opera House, its littered parcel sitting only one diagonal square from the two prior losses. A new decade had dawned, the 1920s, during which preservationist sentiment would foment.

More on that in upcoming Tricentennial features.

- Old French Opera House, photographed by William Henry Jackson in the 1890s. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

- Former St. Louis Hotel, seen here in 1906. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture is the author of “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma,” “Geographies of New Orleans” and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.