MOD MASTERS

LEONARD SPANGENBERG BETTY MOSS EDWARD TSOI

Learn more about three modernist architects who left their mark on mid-century New Orleans from the September issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine.

Woman architects have been practicing in the United States since the 19th century, but the social changes of the 1960s helped to bring an influx of new women to the field. As social movements started to chip away at gender discrimination in the workplace and more women entered male-dominated industries — including architecture — they brought important contributions to the field, often working twice as hard to gain recognition for their work.

One notable New Orleans example is Betty Anne Lipper Moss, a licensed architect with a successful decades-long career that left a legacy on the city’s built environment.

Born in 1921 in Houston, Betty Lipper attended Newcomb College and received a degree in journalism in 1942. After marrying Hartwig Moss II and becoming a mother of two, she returned to Tulane and earned a bachelor’s degree in Architecture in 1960. Beginning her architectural practice in her 40s, she defied the conventional stereotypes of the time of the typical architect.

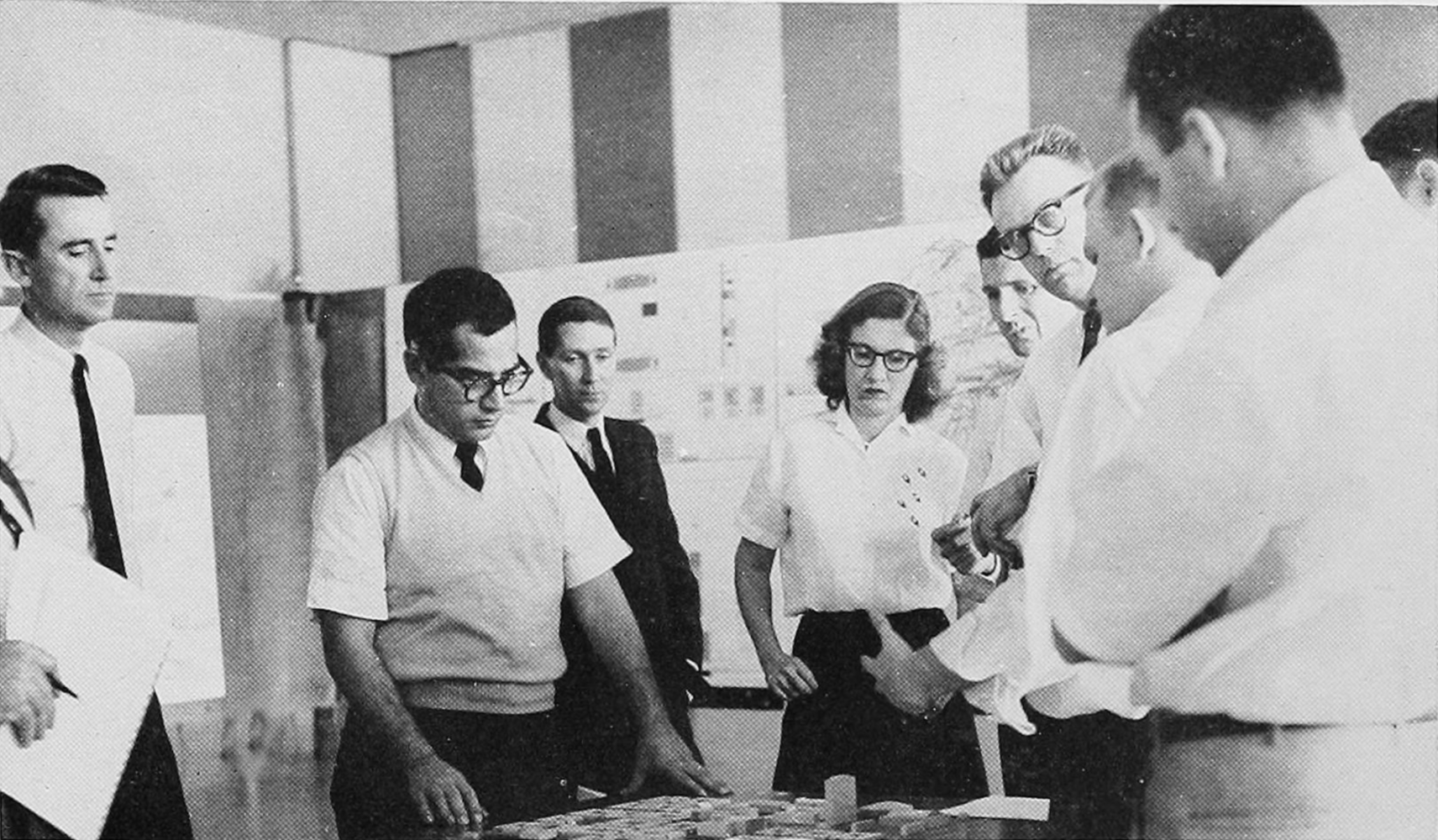

Betty Moss and other Tulane architecture students present semester projects in 1960. Image courtesy of University Archives, Tulane University, Special Collections, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA.

Betty Moss and other Tulane architecture students present semester projects in 1960. Image courtesy of University Archives, Tulane University, Special Collections, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA.

She designed her family’s home in 1950, before receiving formal training as an architect. When she began practicing professionally, some of her commercial work was for Hartwig Moss Insurance Agency, with her husband serving as the client. As her architectural career expanded, she went on to design an array of residential and commercial projects.

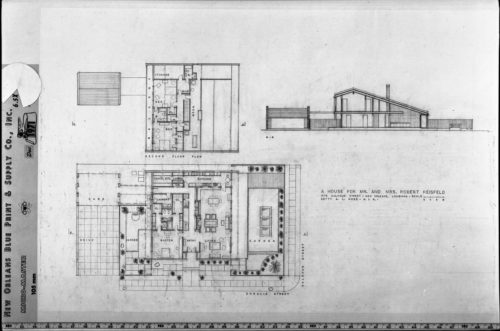

Many of her original plans, drawings and renderings are archived at Virginia Tech’s International Archive of Women in Architecture in Blacksburg, Va. The archive was established in 1985 to document the history of women’s contributions to the built environment. The wide array of projects in the archive’s Betty L. Moss Collection demonstrate her flexibility, and includes designs for religious centers, office buildings, retail spaces, single-family homes and large multifamily residential buildings, as well as restoration projects of historic buildings. Two of her noteworthy modernist residential designs include 1578 Calhoun St., which she designed for the Reisfeld family in 1971; and 741 Topaz St., which she designed for the Maloney family in 1963.

Click images to expand

1578 Calhoun St., one of Moss’ modernist residential designs, stands out among its neighboring Uptown homes.

Photos by Liz Jurey. Architectural plans courtesy of Betty L. Moss Architectural Collection, Ms2008-071, Special Collections, University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

One of Moss’ more unconventional residential designs is the house at 741 Topaz. A series of square rooms, each with its own hipped roof, is clustered around patios in the front and back of the house. Floor-to-ceiling windows and sliding-glass doors open up each room to the patios or to the backyard, bringing ample light into the space and providing a connection between indoor and outdoor areas. The outdoors also are brought to the house’s interior with the use of hemlock paneling, which covers the vaulted hut-shaped ceilings of each room, as well as hemlock louvered folding doors.

Each room is covered with an individual hipped roof, but the overall shape of the one-story home still embodies the horizontality associated with mid-century modern houses, with stretches of flat roof that overhang beyond the exterior brick walls. The patios located in the front of the house are given privacy with louvered screens flush with the front facade, giving the house a unified appearance from the street and providing privacy within. For additional privacy, the front facade uses thin clerestory windows above the brick walls to illuminate the interior.

Click images to expand

Moss’ design of 741 Topaz St. has a distinctive appearance with multiple hipped roofs, wide overhanging eaves and patios concealed behind louvered screens.

Photo by Liz Jurey. Architectural plans courtesy of Betty L. Moss Architectural Collection, Ms2008-071, Special Collections, University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Later in her architectural career, Moss was an avid preservationist who defended threatened historic and modernist architecture. When development plans in the 1990s threatened the demolition of the Rivergate — a 1968 Curtis & Davis-designed exhibition hall constructed with sweeping sculptural concrete — Moss started an organization called “Friends of Rivergate” to advocate for the building’s adaptive reuse. Although the battle was ultimately lost and the Rivergate was demolished in 1995, the fight to save it was one of the earliest efforts in New Orleans to save a threatened modernist building and helped to change New Orleanians’ ideas of what types of architecture are worthy of preservation.

Moss passed away in 2007 after a long and successful career. A memorial page in the November 2007 issue of Preservation in Print lauded Moss’ work as an architect and an advocate of modernism, as well as for her “terrific sense of humor” appreciated by her friends and colleagues. Moss’ legacy can still be seen today with the local buildings she designed, but also through New Orleanians’ renewed appreciation of the mid-century modern architecture for which she advocated.

Davis “Dee” Allen is PRC’s Communications Associate and a staff writer for Preservation in Print.

Advertisements