This story is a tricentennial feature from the April issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

After the death of Pierre de Marigny in 1800, his oldest son Bernard began to plan what he would do with his vast inherited fortune. The purchase of the Louisiana Territory by the United States in 1803 opened the door to great numbers of immigrating Americans. This factor and the success of the enslaved people’s revolution against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue (the Haitian Revolution was from 1791-1804), doubled the population of New Orleans by 1809. Bernard was keenly aware of these world changes and began the process of creating a new suburb, or Faubourg, by subdividing his plantation lands, which were located just downriver from the Vieux Carré.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, New Orleans and the Caribbean grew very close, it was a time of great wealth and cultural development for both the white and free black communities of both locales. Faubourg Marigny, after its subdivision and urban design, became one of the most favored places for the incoming Creoles. By 1807 the majority of the land had been purchased and Creole cottages large and small were built along streets with colorful names like Rue Bon Enfan (Good Children Street) and Champs-Élysées (Elysian Fields Avenue).

A very large portion of these cottages were the homes of free women of color, a group often not recognized for the important role that they played in creating the built environment of New Orleans.

New Orleans was growing in population and importance as one of the world’s leading port cities. Bernard de Marigny, his brother Jean de Marigny and their free woman of color half-sister Eulalie de Mandeville, knew what great opportunities lay in their futures. Bernard and Jean were the sons of Pierre and his wife Jeanne Marie Destrehan. Before this marriage, Eulalie was born to Pierre and Marie Jeane, an enslaved woman born in the Congo, who was given her freedom after the birth of her free-born daughter. Marie Jeane and Eulalie were an integral part of the Marigny family and Eulalie was rightfully viewed and raised as a daughter in the household. Pierre’s mother, Madame de Mandeville, was very close to Eulalie, and supervised her courtship with Eugene McCarty, of the wealthy white McCarty family, who eventually became her husband.

Eulalie is introduced as the first of the free women of color in this article as she is an excellent representative of the wealth and power that drove these women to create such rich and prosperous lives. Eulalie, affectionately known as Madame “Cee Cee” McCarty, and her husband Eugene, raised five children who all became respected members of Creole society. As Eugene was the second son of the McCarty family, he did not inherit a large fortune and utilized loans from Eulalie to develop his successful banking, lumber and dairy businesses. After over 50 years of marriage, Eugene died, leaving his family an estate of over $150,000. Eulalie made her fortune in real estate and through the ownership of several mercantile stores throughout the New Orleans and Mississippi River Region; she ultimately left an estate worth over $250,000. Their combined estates in today’s market would be valued in the millions.

Rossette Rochon is our next important and prosperous free woman of color.

She was born in Mobile in around 1767 to a French ship builder and an enslaved woman of his household. Both mother and infant daughter were given their freedom after the birth, and remained with the shipbuilder as a family unit. Rossette utilized the money that she inherited from her father after his death to move with her mother to New Orleans. She became a successful entrepreneur and landowner, building several fine Creole cottages, two of which still exist today.

One of the homes, an exemplary cottage at 1515 Pauger St. was developed to serve as Musée Rosette Rochon by longtime Marigny preservationist and interior designer Don Richmond, when he purchased the home in 1995. The museum was to be a celebration of the great design and craftsmanship of Creoles of color. Unfortunately, Richmond died before completion of the project, and left the property to the Southern Food and Beverage Museum (SoFAB). After encountering zoning issues, SoFAB sold the home to private owners in order to raise capital for programming.

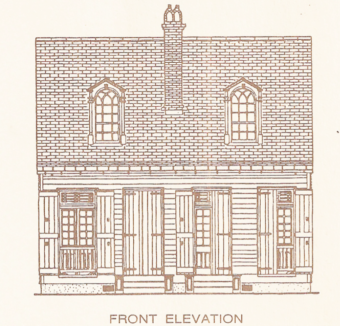

Rosette Rochon’s Cottage, 1515 Pauger St. Elevations by E. Cizek, 2005.

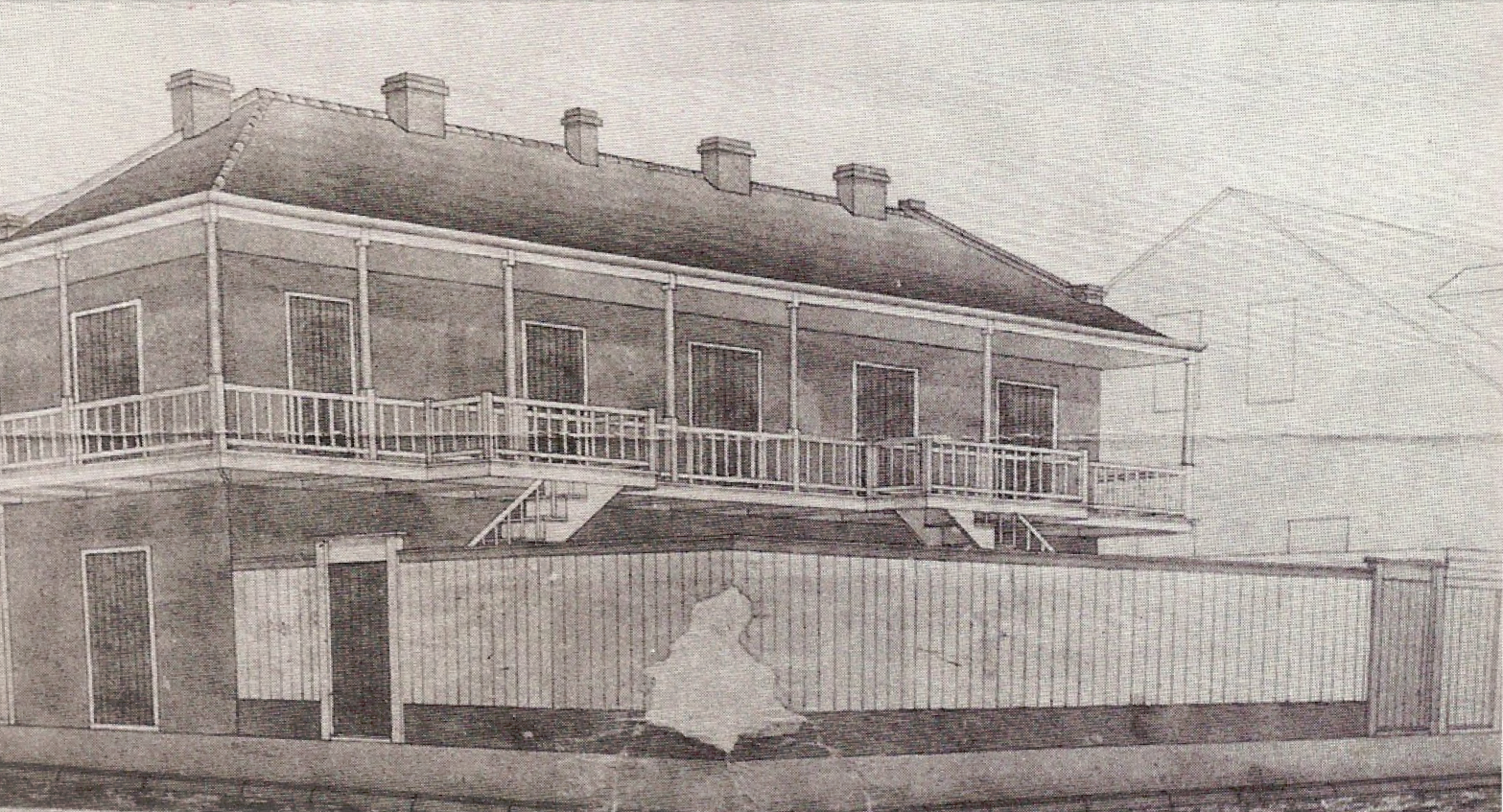

Rossette’s other extant cottage located at 909-11 Touro St. at the corner of Burgundy Street, is adjacent to the popular Ruby Slipper Café, which occupies a very grand brick corner bank building that was constructed on the site of what had been the last of Rossette’s private homes. The design of that home can be viewed as a plan and watercolor in the New Orleans Notarial Archives and in the excellent Friends of the Cabildo publication, New Orleans Architecture: The Creole Faubourgs. This large-roomed, linear, two-story galleried townhouse abuted the lakeside property line and looked out over a grand French-style garden towards Burgundy Street. Rossette’s properties were always built in the Creole style by some of New Orleans’ master builders. The descendants of these talented builders, masons and plasterers are still today considered to be the finest available and in great demand.

Sun Oak, located at 2020 Burgundy St., is my present home and was shared with my partner, Lloyd Sensat, Jr. until his passing. This Creole cottage, featuring a galleried and rusticated façade, appears to be three separate cottages and was originally built by free woman of color Constance Rixner Bouligny in 1807. Constance was a descendant of enslaved Africans, the German Rixner family of St. Charles Parish and the French colonial Bouligny family. The current façade reflects the 1836 Greek Revival renovation by Jewish merchant Asher Moses Nathan, who emigrated from Amsterdam. The renovation was undertaken for the benefit of his female cohabitant with whom he had two children but whose identity remains a mystery.

The last free woman of color presented, who helped to shape the course of Faubourg Marigny’s future, is Maugerite de Bore, who in 1808, at the uptown – lakeside corner of Dauphine and Kerlerec streets, built the smallest of the featured cottages with brick-between-post, heavy-timber construction featuring a trussed roof and a very deep, two fireplace, chimney. The cottage, constructed with strong cypress, was moved easily by utilizing mules and logs, as an infill project in the late 19th century to 926-28 Kerlerec St. When on its original site, the property included a two-story brick structure for the housing of enslaved workers, a one-story brick kitchen, a wooden privy and related outbuildings all fenced as to their individual needs. The ground was covered almost completely by handmade brick, laid in a herringbone pattern, with small raised beds for flowers, herbs and vegetables. The fences were of seven-board design with the beveled edge laid horizontally to deflect water; in Creole architecture all wooden surfaces exposed to the climate must have at least a small bevel to avoid decay.

Madame de Bore’s cottage was my first house in New Orleans. I purchased it in 1971 and sold it in 1976 to begin the torturous restoration of 2020 Burgundy St. I bought the house to serve as the focus of my Ph.D. dissertation in Environmental Social Psychology from Tulane University Graduate School. My graduation, in 1978, reflects the great length of time spent studying Creole architecture and its effect on human occupation, in the search for comfort within the hot, humid climate of New Orleans. My ongoing obsession with Faubourg Marigny kept my students in the Tulane School of Architecture and I busy for almost 50 years of learning, and loving, the academic and hands-on process of historic preservation and environmental conservation.

- Marguerite de Bore’s cottage at 926-28 Kerlerec St.

- Sun Oak, 2018-20 by E. Cizek.

- Last home of Rosette Rochon, Corner of Touro and Burgundy Streets, now site of the Ruby Slipper Café. Image from New Orleans Architecture: the Creole Faubourgs