This story is from the archives of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

New Orleanians know the power of a good grocery store.

We’ve all heard old timers wax poetic about “making groceries” at Schwegmann’s, Circle Foods, Langenstein’s and Solari’s, but what they miss is more than just a place to buy food. Grocery stores, neighborhood markets and corner stores have long served as social and cultural glues that bind New Orleans’ unique neighborhoods, and the people who live within them, together. Since the founding of the city, shopping for fresh food near their homes has been an opportunity for residents to run into neighbors, talk about community, support local farmers and businesspeople, and yes, buy the staples and local delicacies needed to cook their families the delectable dishes for which the city is known.

All the way back in 1822, the construction of the St. Mary’s Market on the corner of St. Joseph and Tchoupitoulas streets helped “to create a thriving residential and commercial neighborhood with…merchants of every description who followed the market’s lead to create a flourishing mixed-use community.” Almost 200 years ago, just like today, stores that served neighborhoods with fresh food kept the local economies, block-by-block, alive and thriving.

While the rise of suburban supermarkets rendered them obsolete decades ago, the importance of such grocery stores within the community still holds weight to residents of this city. In fact, the subject of where New Orleanians buy their food is potent as ever. Consider a report done by StoryCorps New Orleans in 2010 about a family that evacuated to Texas for Hurricane Katrina and whose matriarch still refuses to return until Circle Foods on St. Bernard Avenue reopens. Or the responsibility Ray Khalaileh, 17-year owner of Jimmy’s Grocery on Dauphine Street, felt when policemen and neighbors told him that his corner store’s reopening in the weeks after Katrina was a key factor in helping residents feel safe about coming back to Bywater. Consider the buzz that floods the city when new food stores open, such as the Rouses in the Central Business District or the Fresh Market coming to St. Charles Avenue.

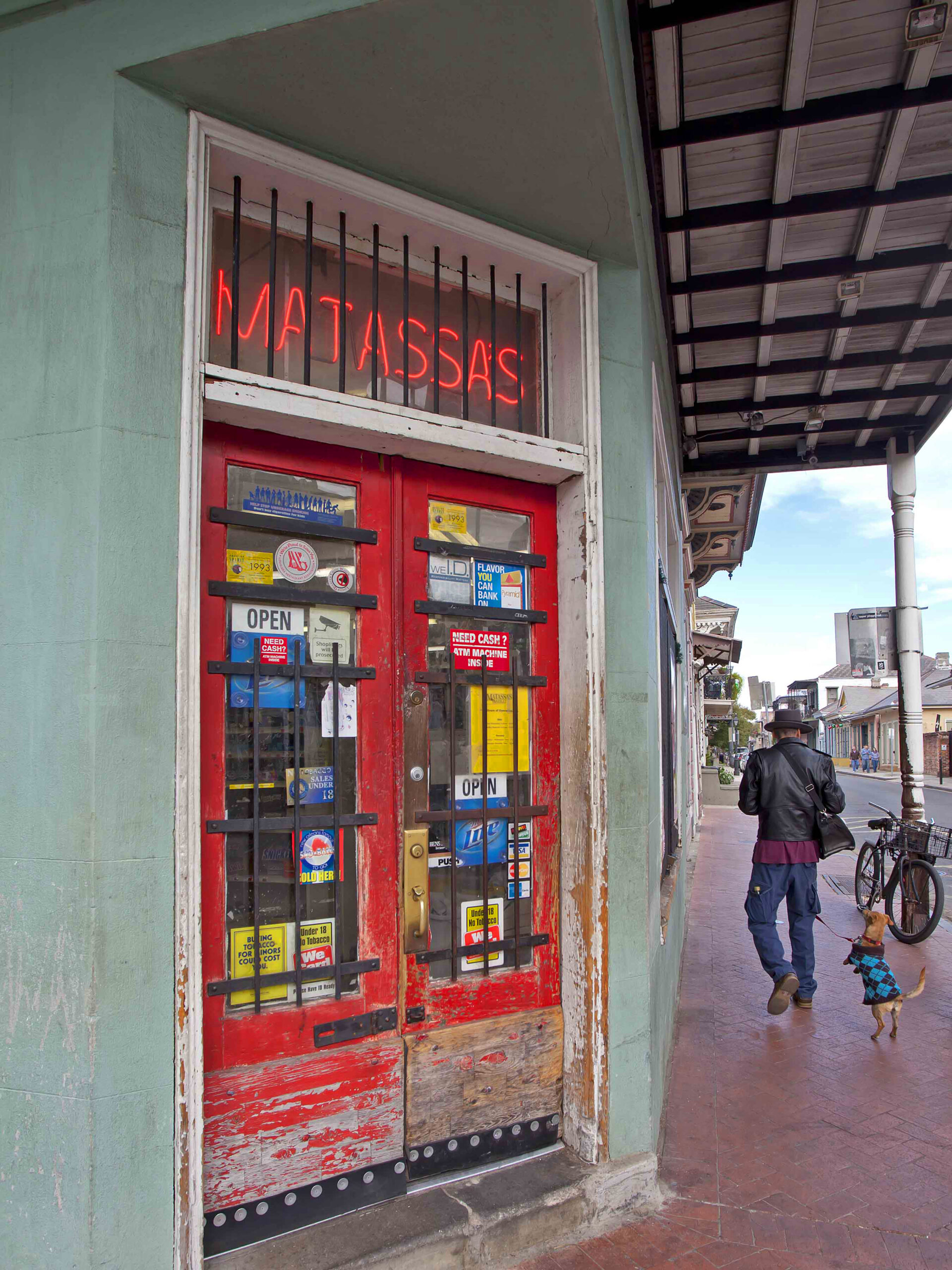

Ask residents of the city’s historic neighborhoods how they feel about their local grocery stores, and make yourself comfortable — you’re in for an earful. If they’re fortunate to live near a successful neighborhood store, such as Matassa’s in the French Quarter or Langenstein’s Uptown, residents will tell you how much they appreciate the convenience of being able to run to the store for a few small items and the comfort of seeing their friends while shopping, and often they’ll reminisce about how they grew up shopping there. More often in this supermarket age, though, you’ll hear residents of New Orleans’ historic boroughs talk about how they’re not able to shop local. For a city with the neighborhood density, walkability and bikeability that New Orleans boasts to be so lacking in fresh food stores within proximity to their homes is a source of contention for many residents of Bywater, Tremé, Broadmoor and other areas. “We have to drive five to six miles just to get to a real grocery store,” said Kim Collins, a longtime Bywater resident. “We need a grocery store.”

1: Matass’a Market at 1001 Dauphine St.

2: Louis Matassa inside his French Quarter store.

It’s not just the natives who lament. New Orleans’ historic architecture, affordability, unique culture and the state’s lucrative tax incentives have recently been luring a creative class of filmmakers, entrepreneurs and inspired young people like never before, and these newcomers are looking to live within the mixed-use streetscapes for which New Orleans is known. Tracey LaFrano, who moved from New York City to start graduate school at Tulane University this past fall, was seriously considering renting an apartment Uptown until she found out that the block’s bodega was closed and, due to lapsed zoning permits, probably wouldn’t be coming back. “People are willing to pay for convenience; for me that includes being able to walk a few blocks for the couple of bags of groceries I need that are not too heavy to carry home,” she said. She chose a different apartment to rent, one within easy walking distance to stores like Breaux Mart on Magazine Street.

Though residents across the city echo Collins’ and LaFrano’s desires, grocery distributors, according to Louis Matassa and other owners of smaller grocery stores, regularly claim that historic neighborhoods just can’t support full-service stores. Bywater residents know this well; according to members of the Bywater Neighborhood Association, recent plans to open a branch of an established local grocery chain on St. Claude Avenue were abandoned when distributors and backers decided the profit margins just couldn’t cut it. It’s a phrase oft-repeated: “The numbers just don’t work.”

The lack of readily available fresh food in many of the city’s neighborhoods is such a large problem that New Orleans was named the country’s number one urban food desert this past September by NewsOne network, a designation bolstered by USDA food availability statistics. Sure, corner stores abound in the city’s neighborhoods, but they’re not the corner stores of yore. Instead, they’re stocked with malt liquor and junk food, with nary a vegetable in sight. A lack of proximate, fresh food grocers for many of the city’s residents raises a myriad of public health and social justice issues — especially for lower income residents, many without cars, when they are unable to both shop for healthful food in their neighborhoods or easily travel to full-service grocers elsewhere.

City officials, residents, newcomers, urban planners and local entrepreneurs see the problem and are in accordance for the solution: Supporting the creation of more grocery stores within New Orleans’ neighborhoods will bring convenience and improve health and equity issues, yes, but it will also spur job creation and foster local entrepreneurialism. Grocery stores have the power to further revitalize blossoming blocks and whole swaths of historic neighborhoods; indeed, they are a key link in mending many of the city’s most serious issues.

Wheels are in motion: A number of new grocery stores are in the works, others have recently opened and the city has even debuted an initiative that will lend $14 million to support new fresh food retail initiatives. In the era of the suburban supermarket, it may prove impossible to revive the neighborhood grocery culture that historically has given so much to New Orleans’ citizens. But it seems that a few well-informed entrepreneurs are determined to try.

Though the city’s history celebrates the important and extensive impacts of both fresh food markets and corner stores, the two did not co-exist harmoniously, according to Richard Campanella, professor of geography at the Tulane School of Architecture and author of six critically acclaimed books on the physical and human geography of New Orleans. “In the 1800s, municipal markets dominated food retail in New Orleans; competition came from an intricate array of street peddlers and some small store-based grocers,” he said. By the turn of the 20th century, corner stores, many of which were established by Sicilians who had gotten their start in market stalls, were becoming pervasive. “Their intentionally dispersed geography, plus technologies like electricity and refrigeration, gave the corner grocers a major competitive advantage over centralized markets: convenience,” Campanella said. “The city fought back with a 1901 law that prohibited groceries to open within nine blocks of a municipal market, but markets became increasingly ill-suited for 20th-century city life, and corner grocery stores continued to draw away consumers until the rise of auto-accessed supermarkets.”

With the rise of the automobile came the invention of the supermarket, which in New Orleans was pioneered by the Schwegmann family. “Supermarkets, franchises, suburbanization, and finally nationalized and globalized food production and distribution” redefined the geography of food retail, said Campanella, dealing the last blow to the city’s markets. “Most markets closed by the late 1950s, their structures either demolished or retrofit for other uses.” Corner stores weren’t faring much better. “Zoning further impeded corner stores: designed to segregate land uses to preserve residential property values, zoning ordinances tore apart the historical urban fabric that encouraged local micro-enterprises to set up right next to their clients,” he said.

In his book Bienville’s Dilemma, Campenella describes what happened next. “After the demise of markets and corner stores, local retail chains (namely Schwegmann’s), plus increasing numbers of regional and national chains (such as Winn-Dixie and later Sav-a-Center), came to dominate the New Orleans food market. By century’s end, Schwegmann’s closed and Winn-Dixie, Sav-a-Center and finally Wal-Mart garnered the lion’s share of the market. While some single-location independents and small local chains (Langenstein’s, Ferrara’s, Zuppardo’s, Zara’s and others) still dot the cityscape, most New Orleanians spend most of their food dollars at national big-box chains.”

And here we are today. As Campanella notes, the rise of Rouses’ popularity in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, “to the delight of many New Orleanians brought back many traditional local food specialties to the city’s supermarket shelves.” And local leader Richard McCarthy has reinvented the city’s market traditions through the Crescent City Farmer’s Market, which operates in different neighborhoods three times per week and is now in its 17th year of operation. But true full-service, neighborhood grocery stores are rare. Louis Matassa and his brother John have kept their corner grocery store, Matassa’s, alive in the French Quarter for over four decades, but he admits that they’re “lucky.” “We’ve been here a long time, and people support us,” he said. The small grocery and grill has been open on the corner of Dauphine and St. Phillip streets since 1924 and stocks most food items and household supplies that neighbors might need. “I know my customers, and they know us. They’re loyal,” he said.

3: The Rouse’s in the Central Business District, located in a former car dealership building.

Though it is in many ways a quintessential neighborhood grocery, Matassa’s model for success isn’t failsafe — in fact, it failed not even a half-mile away when Louis and John tried opening a second location in the Upper Quarter. “We went broke,” Louis said. “It’s just not feasible to go in to some areas. I wanted to open a store in between the Marigny and Bywater, and my grocery company said, ‘Look: The numbers came back, and they’re not good.’ Here, we’ve been open for years, people know us. But trying to start somewhere new…” He shook his head.

It may seem illogical to residents of underserved neighborhoods that retailers would be discouraged from opening in their area when they and everyone they know want to shop close to their homes, but it’s a reality that every grocer in this city faces: More often than not, the numbers just don’t work. Says Campanella: “I had the opportunity to review a quantitative market study conducted to determine the viability of a local mid-size grocer to invest in a historical neighborhood that lacked one and whose neighborhood association strongly desired and encouraged one. The study concluded “no-go.” I went through their data and analysis with a fine-toothed comb, but found no flaws to contest. The for-profit private sector is very savvy; if investors are confident they can make money, they’ll try.”

Jimmy’s Grocery owner Ray Khalaileh has never been one to ignore a hunch because of the numbers, and he claims to have bucked that eventuality when he opened a second grocery store in Bywater, Dora’s Grocery on St. Claude Avenue, in 2007. His vendors thought Khalaileh had lost his mind when he shared his plans to stock both higher end products, like imported beers and pricey wines, along with prepackaged meats, Hispanic brands and staples like fresh fruits and veggies. “The wine people used to tell me, ‘There’s no way you can make it here. This is St. Claude, not St. Charles,’” he said. (A sad reality considering the original Schwegmann’s supermarket was built, and thrived, on the corner of St. Claude Avenue and Elysian Fields.)

4: Jimmy’s Grocery, formerly located at 4201 Dauphine St., now closed.

But he believed his store would be a success and stayed firm, even enduring losses in his first few months. Khalaileh capitalized on specials offered by vendors to keep prices low and discounted specialty merchandise to lure customers in. Soon, business was booming, and he was bringing in $7,000 a day. “One business owner taking a chance can improve the market as a whole in an area,” he said. “It takes that one person to take the leap of faith.”

Faith is fine, but food distributors want to see dollars. A full-service grocery that boasts affordability can survive and thrive in the Ninth Ward, Khalaileh believes, but it would have to draw its profit by attracting the largest number of people possible. “You have to cater to all residents, not just a distinct subset, and work with vendors to capitalize on specials so that you can price goods affordably for shoppers” if you’re looking for numbers, Khalaileh said. “The numbers are there, but the way you attract your customers is the key.” Appealing to all subsets of a neighborhood’s demographic, as Khalaileh suggests, could apply in virtually every neighborhood in New Orleans, though it’s undeniable that other stores have thrived by catering to a more affluent subset of the population. Those stores, such as Langenstein’s Uptown, can charge more and offer an array of specialty foods to offset costs and therefore can thrive in certain areas of town. But for a section as diverse as the Ninth Ward, a truly transformative grocery store would need to serve everyone. “If you had the right grocery store, one that could make everyone happy, this would be the best neighborhood in the city,” he said. “It would be packed. It would bring more people to live here, and it would make the other side of St. Claude better, too.”

Such optimism recently spurred an attempt to redevelop the remains of a shuttered school site in the historic Holy Cross neighborhood into a full service grocery store with attached affordable housing for teachers: Sterling Farms, a company created by actor Wendell Pierce and local developer Troy Henry, tinkered with a plan for months to open a 25,000 square foot, full-service grocery store on the former Holy Cross School site. While many in the Upper and Lower Ninth Ward were excited by the prospect, doubters who pontificate on online message boards and at neighborhood meetings are skeptical that such a large store could thrive in an area still recovering from a dramatic depopulation following Hurricane Katrina. They might be right: Green Coast Development, the firm working with Sterling Farms and others, announced in February that financing had fallen through, and the deal had died. Despite this, sources say that others are interested in possibly redeveloping that site to include a grocery store, and that even though Sterling Farms didn’t acquire the Holy Cross site, they still hope to open a grocery store somewhere in the Lower Ninth. “As they should,” said Austin Allen, an associate professor of landscape architecture at LSU who lives in Holy Cross and helped in the creation of a Lower Ninth Ward master plan immediately following the storm. “We should be basing profit equations on the projected population of the area in five years. That’s what the feds and the city are doing — they’re putting $40 million into street improvements in the Lower Ninth Ward because they, like me, have seen the interest and think the Lower Ninth’s population will continue to grow.

“This is the recovery of a neighborhood, of a place. This store would be a first piece and would lead to a bigger buy in” from other businesses and from neighbors on both sides of St. Claude Avenue and the Industrial Canal, he said.

It is Allen’s personal hope that the site could be developed as a grocery store/food co-op hybrid. “A well thought-out food co-op fosters food understanding,” he said. “You’re seeing health products, vitamins — that is a critical part of food education.” He is especially inspired by a food co-op in Atlanta called Sevananda Natural Foods Market, which has successfully served a diverse local population for decades. “There’s an assumption that amongst poor people and black folks there’s not an interest in that, but there’s a great interest,” he said. “It started with the Sankofa Market, and what they’re doing could easily evolve into a food co-operative. Yes, the Healing Center’s co-op’s offerings are different than what much of the population of the Upper Ninth is used to. And after a while, the prices make sense.” The Healing Center’s food co-op has several incentives and opportunities for patrons who shop with food stamps, he pointed out. Ultimately, Allen said, “It can cause a shift. And that would be good for the Lower Ninth.”

Rethinking the set method for stocking a grocery store’s shelves, as Allen suggests, could be a crucial component in a neighborhood store’s success. Aside from attracting the number of shoppers necessary to be profitable, many small grocery retailers agree that their biggest problem lies in sourcing items. As Khalaileh explains it, food distributors that stock grocery stores have item catalogs for two markets: big supermarket groceries and small convenience stores. This means that smaller storeowners who want to stock their shelves with more than chips, soft drinks and other corner store staples often simply can’t. While his long-standing relationship with his vendors has given Khalaileh access to a larger array of groceries than a store his size would typically have, product availability is sporadic, and often, Khalaileh is forced to carry certain brands or larger quantities because his vendors are stocking them in the larger grocery stores. “I sell more Naked Juices than anybody else, but my milk man told me it’s hard for him to get them for me because only big supermarkets are allowed to have them. Sometimes I run out of a product and I cannot get it from the vendor, so I have to go to Sam’s Club to get it. And that makes the price go up. But the price has to be reasonable for the neighborhood; just because I sell it doesn’t mean I should sell it too high.” It’s a difficult reality that keeps residents grumbling — even if they are able to buy fresh or specialty food items in their neighborhoods, prices can be astronomical. Louis Matassa concedes that his store’s success is largely thanks to a partnership with a food vendor that is willing to stock his store with the wide array of products that a supermarket carries. “Associated Grocers out of Baton Rouge is a great wholesaler,” he said. “They give us a lot of support, and buying power. They supply me, Dorgniacs, Breaux Mart, Robért — most of the independents in the city today.”

That list describes mid-sized stores, though, which still doesn’t help those with prospects or wishes for more small corner groceries in the city. Campanella sees that this problem of food distribution, combined with the problem of making numbers work, will ultimately keep the neighborhood grocer from regaining its historical prominence. “I think we’ll see a small re-blossoming of neighborhood-scale food retailers and restaurants, but they will be skewed toward specialty foods, goods and services — more on the “boutique” end than the “best-deal-for-your-buck” end,” he said. “Until local neighborhood retailers can figure out how to match the economies-of-scale, variety and convenience of drive-up supermarkets, most folks in the metro area, I believe, will continue to buy most of their calories in big boxes.”

Since retailers may be years away from figuring out a reconfiguration of the typical grocery model, city officials are stepping in to promote and help fund the opening of neighborhood stores. The Mayor’s Office for Economic Development has an initiative to help ambitious grocers who are willing to take the leap and open a store in an underserved area: The Fresh Food Retailer Initiative (FFRI) program debuted in March 2011 with $14 million in funding — $7 million from city Disaster Community Development Block funds and $7 million from Hope Enterprise Corporation, a mid South lender — to distribute as low-interest and forgivable loans to approved grocery projects. “This was driven from a desire to respond to the fact that there are a number of food deserts in the city and to encourage healthy food, jobs and revitalize our neighborhoods,” said Aimee Quirk, advisor to the mayor for economic development. “And it includes many historic structures in need of redevelopment, putting property that has been underutilized back in commerce, so it’s win-win in terms of our policy goals.”

Indeed, the first (and only, as of press deadline) FFRI award has gone to a project that will reuse, after renovation, an existing building and empower a local entrepreneur. Douglas Kariker lives less than a mile from Baronne Street and Jackson Avenue, the corner where he will soon open DaFresh Seafood and Produce Store thanks to a FFRI loan of $117,000, $11,700 of which is forgivable. Kariker’s project will cost upwards of $250,000, employ up to eight people and bring healthful groceries to a swath of Central City in short supply.

While this first award went to the little guy, Quirk said that FFRI money can go to grocery store projects and purveyors of all sizes and scopes. “We look at location — Is it in an underserved part of the city? Is the operator someone experienced in the industry? Is there a track record that the store will be well run and maintained? Is there a good financial model? Do they have other sources of funding lined up?” she said. Over 30 FFRI applications have been submitted thus far, with a healthy amount of “interest from small businesses,” she said.

This is Kariker’s first entrepreneurial endeavor, though he does have a family member in the seafood business, according to the city’s press release. Such a selection will be music to the ears of applicants like Naydja Bynum, whose proposal through the Institute of Community Development, a nonprofit run by Bynum, her husband Adolph and Tremé Neighborhood Association Executive Director Jessica Knox, for a small fresh food grocery in historic Tremé was initially denied on the grounds that the manager, her stepson, was under qualified. Bynum’s family operated a pharmacy in Gentilly for 55 years, and feeling that was experience enough, they appealed. “If you’re going to go to a poor area without fresh food, you’re not likely going to find someone in the community with experience in that business,” Bynum said. “So what are you going to do, bring a developer in from outside? That’s not helping anyone empower themselves or improve the economics of the people who live here.” Happily, Bynum reports, further talks with the city have gone well, and officials, after further clarification from the Tremé team, are allowing an appeal. “The jury’s still out,” she said. “We’ll have to see what happens.”

Residents are watching, waiting, and when they can, shopping. Responding to the needs of the active and growing downtown population, the Rouse family recently converted a former Cadillac dealership into a 40,000 square foot grocery store on Baronne Street. The project has been heralded a raging success so far and espouses the smart-planning approach to grocery store creation that the city should embrace: The Rouses adapted an existing building for reuse, thereby maintaining the historic streetscape and utilizing existing resources; it is further revitalizing downtown’s Loyola corridor, which will soon have a streetcar; and, oh yes, it is selling fresh, affordable groceries.

There are a number of other projects around the city currently in the works: A Winn-Dixie is planned for a site on Carrollton Avenue across from a Rouses, the former Borders bookstore on St. Charles Avenue will soon open as a Fresh Market, a North Carolina-based luxury food chain, and already, smaller stores such as Poeyfarre Market and the Food Co-op are providing staple and specialty items to residents in their respective neighborhoods.

Another possible solution could lie in retrofitting existing corner stores with fresh produce; past initiatives by Louisiana2Step, a program of Blue Cross and Blue Shield, and the Tulane School of Public Health that brought fresh food to corner stores did have some impact after the storm. Bringing healthful foods to existing stores could allay the startup costs and risks that doom the prospects of potential new groceries within neighborhoods. Walgreens has recently retrofitted 10 stores in Chicago as “food oases” with large selections of fresh food, and has promised to outfit 1,000 other stores nationally in the next five years. With 25 locations in New Orleans, could that project affect the city?

As new projects come online, residents wonder, what will survive? What neighborhoods will benefit? The city’s fresh food availability saga continues.