This story first appeared in the March issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

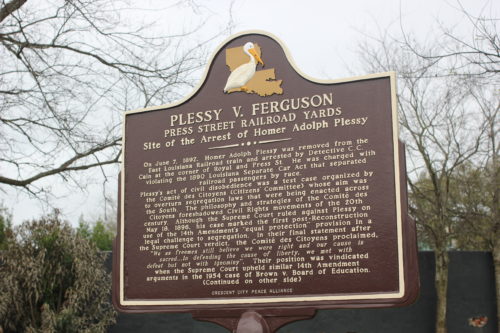

Plessy V. Ferguson is arguably Louisiana’s most famous Supreme Court Case. It involved a group of men who sought to challenge Louisiana’s passage of a law that separated blacks and whites on railroad trains. This group of writers, businessmen, educators, lawyers and a newspaper publisher constructed a well-planned legal and civil disobedience campaign to have the law overturned in the courts of the land and also in the court of public opinion.

Homer Plessy was born ‘Homere Patris Plessy’ in New Orleans on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1863. His father was a carpenter; his mother Rosalie was a seamstress. Homer’s grandfather, Germain Plessy, was a native of France who arrived in New Orleans from Haiti in the early 1800s. He fathered a number of descendants through a union with a free woman of color named Agnes Mathieu.

Homer Plessy was born two months after the Emancipation Proclamation became effective in Louisiana. His early life paralleled Reconstruction and the expansion of citizenship rights for people of African descent. He grew up with the right to vote, seek public office and travel on public conveyances without molest. Interracial marriages were legalized and the Louisiana Constitution of 1868 integrated the school system. Homer wasn’t as well known or as prosperous as others on the Comité des Citoyens (Citizens’ Committee), the civil rights group he would later join and act on behalf of. He became an active education reform movement advocate in New Orleans. In 1888, he married Louise Bordenave. On June 25, 1868, Louisiana rejoined the Union and approved the Fourteenth Amendment two days later. The following month in July of 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment granted equal protection of the law to all male citizens regardless of color.

It was in 1890 that the legislature passed a mean-spirited law that segregated people on railroad trains. In the case of interracial couples, the law physically separated husbands, wives and children. The law also mandated that railroad companies provide an additional coach even if only a few black passengers purchased tickets. For Louisiana legislators of African heritage (there were 18 black members of the legislature at the time), the law prohibited them from traveling with their fellow government officials and many of their constituents.

In 1891, eighteen prominent New Orleanians reported to the offices of The Crusader newspaper on Exchange Alley. Their mission was to construct a legal, social and civil disobedience campaign against racial segregation. The Comité des Citoyens included an assortment of professionals: educators, businessmen, lawyers, ex-Union soldiers, government workers and writers. Many came from the free people of color caste that existed in Louisiana before the Civil War.

In September of 1891, the Comité des Citoyens issued An Appeal:

No further time should be lost. We should make a definite effort to resist legally the operation of the Separate Car Act. This obnoxious measure is the concern of all our citizens who are opposed to caste legislation and its consequent injustices and crimes…We therefore appeal to the citizens of New Orleans, of Louisiana, and of the whole union to give their moral sanction and financial aid in our endeavors to have that oppressive law annulled by the courts.

The newly formed Comité des Citoyens and their allies filled the autumn and winter of 1891 with urgent appeals. They turned to the tightly knit networks of benevolent and religious societies, labor clubs, lodges and church groups in 1890s New Orleans as their core constituency. Individuals walked the streets with subscription lists, asking their friends and neighbors to contribute. Supporters sponsored concerts and wrote letters.

In their appeal, the Comité des Citoyens asked for financial support “whereby the coins of the poor may equal in merit the liberality of the rich.”

In the short three months after An Appeal was published, nearly $3,000 rolled in from the neighborhoods of New Orleans and in cities as far away as Chicago and San Francisco. In total, over 150 donors contributed to the effort. In 1892, it was time to act.

For Homer Plessy, the law meant that, after years of relative freedom, he was being denied the opportunity to ride in the same car as his next-door neighbor. When the committee sought volunteers, Homer stepped forward. Plessy was more than an accidental activist. Indeed, his arrest and court battle was part of a meticulously planned scenario whereby Homer Plessy would obtain a ticket, board the East Louisiana Railroad on Press Street, and be arrested and booked.

Plessy had four tasks: get the ticket, get on the train, get arrested, and get booked. On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy traveled the nearly two miles from his residence in the Tremé neighborhood to the train station on Press Street, about two miles away. He purchased a first class ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad number eight train that was scheduled to depart at 4:15 p.m. for a two-hour run to Covington, LA. As boarding time neared, Homer walked toward the first class coach ignoring the cars with the ‘Colored Only’ designations. He likewise disregarded the prominently posted ‘Separate Car Act’ signs, and took a seat in the first class accommodation. The whistle blew, the doors shut, the steam blasted from the engine and the East Louisiana train’s wheels creaked forward. As the train inched away, Conductor J. J. Dowling collected tickets. He paused when he got to Plessy; Then, the question:

“Are you a colored man?”

“Yes,” said Homer Plessy.

“Then you will have to retire to the colored car,” Dowling responded.

Homer asserted that he was an American citizen who paid for his ticket and intended to ride to Covington. Dowling then signaled the engineer, who brought the number eight train to a dead stop.

Detective Cain then took over and cautioned Plessy, “If you are colored you should go into the car set apart for your race. The law is plain and must be obeyed.”

Again, Plessy refused to budge and said he would rather go to jail than abandon the coach. At 4:35 p.m., 20 minutes after the train’s scheduled departure, Detective Cain and ‘volunteers’ on the train forcibly dragged Plessy from the ‘White Only’ coach and executed the arrest somewhere near Royal and Press Streets. At the Fifth Precinct Station on Elysian Fields Avenue, Plessy submitted to the same booking procedure applied to the array of drunks, petty larcenists and foul-mouthed New Orleanians arrested that day on the city’s streets. However, his charge of “Violating the Separate Car Act” was anything but a typical Tuesday evening New Orleans petty crime. Members of the Committee converged at the Fifth Precinct Station and had Plessy released on bond. Homer still held his first class ticket as he and his compatriots walked from the police station and made their way across Elysian Fields Avenue and back toward Tremé. They had just purposefully, intentionally and openly defied Governor Murphy Foster, Supreme Court Chief Justice Francis Nicholls and the 1890 Louisiana State Legislature. Homer was not even 30 years old, yet the future of civil rights rode on his day in court. He appeared before Judge Ferguson in November of 1892, who ruled against him.

In December of 1892, the State Supreme Court of Louisiana upheld the decision. In January of 1893, they filed papers to bring their case before the United States Supreme Court. The Louisiana State Legislature also noticed the Supreme Court’s changing temper. In the 1894 session of the General Assembly of the state legislature, they mandated that “marriage between white persons and persons of color is prohibited, and the celebration of all such marriages is forbidden and such celebration carries with it no effect and is null and void.” Then, on July 12, 1894, the legislature amended and re-enacted the 1890 Separate Car Act to mandate separate railroad waiting rooms as well as railroad cars.

In May of 1896, the Court ruled seven-to-one against them. But the majority opinion was not the only voice spoken from the Supreme Court on the Plessy matter that day. Reflecting the brief of Albion W. Tourgee and the philosophy of the Comité des Citoyens, Justice John Harlan issued a powerfully eloquent dissent used as a beacon by civil rights legal activists for years to come. So while the majority of Supreme Court justices ruled against Plessy and the Comité des Citoyens, the Harlan dissent planted their flag eternally in the annals of United States jurisprudence. After the decision, the Comité des Citoyens disbanded. For Homer Plessy, there was still one final matter. His shoemaking days over, Plessy now worked as a laborer. He had ceased to be ‘Plessy the shoemaker,’ or ‘Plessy the challenge to segregation.’ Now, it was ‘Plessy the Supreme Court decision in support of racial separation.’ Wrongly, his name became associated with the existence of Jim Crow laws rather than with an early legal, social and moral movement to end them. Plessy changed his plea to guilty, paid a $25 fine and walked out into a brave new world of American Apartheid.

Homer Plessy died in 1925. In his last years, it must have seemed that segregation was a permanent state, as the Ku Klux Klan held a demonstration of 25,000 in Washington, D.C.. But the arguments presented by Plessy, Albion Tourgee and the Comité des Citoyens were redeemed in 1954 when the United States Supreme Court struck down the decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. It took more than half a century, but ultimately, Homer Plessy won.

Another mural adjacent to the Homer Plessy historical site depicts the three six-year-old African-American girls who integrated McDonogh 19 in 1960: Gail Etienne, Tessie Prevost and Leona Tate. The mural is by Ayo Scott.

Join the PRC on March 16 for the 41st annual Julia Jump at NOCCA’s Solomon Hall, a beautiful adaptive reuse project of a former warehouse that once served the East Louisiana Railroad. The building historically had a railroad stop just yards away, where Homer Plessy boarded a train in 1892 to challenge the Separate Car Act. Purchase your tickets here and see how your support leaves a lasting impact on New Orleans.