This story appeared in the October issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

What makes a building sustainable? There are as many answers as there are definitions of that word. Most would invoke its architecture — its design, materials, construction techniques and infrastructure. Others might mention its owners and occupants, and their use and maintenance of the structure.

Then there is the building’s geography. Good site selection goes a long way toward increasing viability and reducing risk. But locate a structure at a tenuous site, and its fine design and committed occupants will have limited influence over its eventual fate.

Take, for example, Monsplaisir. This splendid colonial country house, located in what is now Gretna’s McDonoghville riverfront, pitted excellent architecture and engaged owners against… well, let’s start from the beginning.

Monsplaisir was built in the early 1750s by Alexandre de Batz for the Chevalier Jean-Charles de Pradel, a member of Louisiana’s founder generation and, for a while, a commandant at Natchez before settling down on a plantation across the river from New Orleans.

In the annals of early Louisiana architecture, De Batz is equally prominent, as a versatile draftsman and engineer responsible for the predecessors of today’s Old Ursuline Convent and St. Louis Cathedral, among other buildings. His documentation of the Company Plantation in what is now Algiers Point, which the late architect Samuel Wilson Jr. described in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (1963) and Louisiana History (1990), showed De Batz to be a key figure in an important transitional period in Louisiana architecture. He adapted New Orleans’ very early “medieval”-looking French structures — built on wet soil, with exposed colombage (half-timber) walls, hardly any overhanging eaves and no galleries — to “the exigencies of climate,” giving rise to the “typical… Louisiana plantation house” erected by the hundreds over the next century. Those subtropical adaptations included raised construction, clapboard-covered walls and oversized pavilion-like roofs allowing for airy galleries with outdoor staircases — edifices that looked more like their similarly “Creolized” colonial counterparts in the tropical West Indies, than their provenances in temperate France.

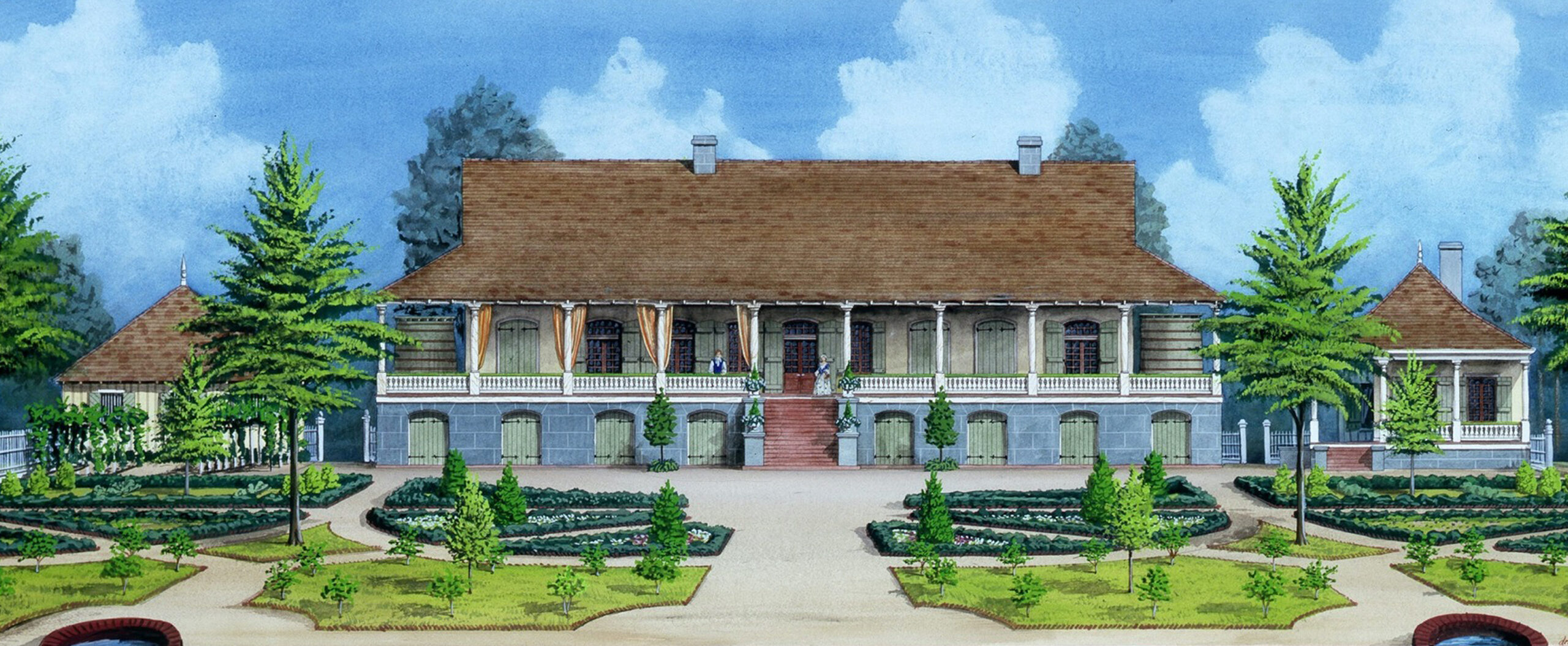

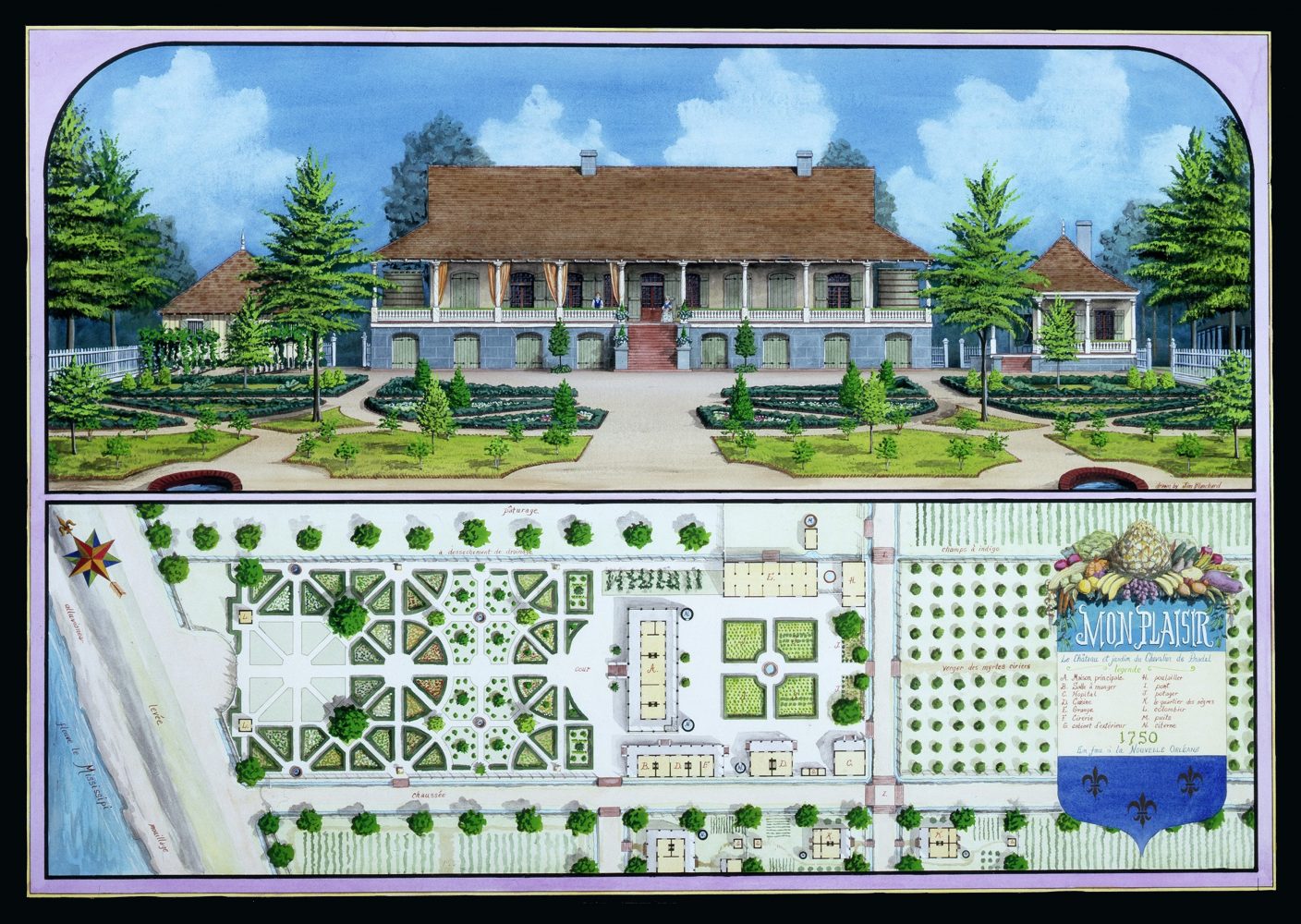

Monsplaisir was built in the early 1750s in what is now Gretna’s riverfront. It is depicted here in a painting by Jim Blanchard, a contemporary topographical artist known for his architectural watercolors of historic Louisiana buildings. Image courtesy of Jim Blanchard and The Historic New Orleans Collection.

It’s that type of house that De Batz designed for De Pradel in 1750, in what today would be Gretna on the West Bank, known at the time as the Right Bank. The site was the next concession upriver from the Company Plantation (by this time known as the King’s Plantation — today’s Algiers Point), owned by Governor Étienne de Périer and sold in 1737 to Jean-Charles de Pradel.

As De Pradel approached retirement, he commissioned De Batz to build him a commodious and well- accoutred house to serve as a pleasant country chateau as well as a headquarters for a working plantation and a lumber operation. Named Monsplaisir (Mon Plaisir, “My Pleasure”), the house was extraordinary for its size, salience and beauty in both design and landscaping — the sort of gardened villa one might associate more with the prosperous antebellum era than the hardscrapple colonial era. “It will be one hundred sixteen feet in length by 48 in width, including the galleries,” wrote De Pradel to his brothers in France while the house was under construction in May 1751. “What a great convenience these galleries are in this country!” he said of its wooden wrap-around verandahs, the middle section of which would have a “large and fine flight of steps.”

In Wilson’s translation of the 1751 letter, De Pradel went on to describe Monsplaisir’s 90-foot-long ell wing “three feet above the ground, surrounded also with a gallery, [within] which are the dining room, the larders, the kitchen, the laundry and the wax works where my boilers are,” likely a reference to the colony’s effort to launch a candle-making industry from local bayberry (wax myrtle) trees. Beaming proudly to his kin back home, De Pradel wrote, “You will see by this plan, and still better by the one of my whole plantation…which this Monsieur De Bat[z] has promised to draw up for me, that, although we may be in another world than France, we like our comforts and…conveniences as best we can.”

Advertisement

Perhaps a few too many comforts and conveniences. De Pradel got carried away with expenditures on the best materials, pricey furnishings from France, “mirrors, marble tables, tapestries,” and more. He came to regret his own decisions, bemoaning “the folly of my Castel Novo,” even dubbing it “Pradel’s folly.”

But by late 1753, he wrote in a subsequent letter, “the folly is done…and I am daily working with pleasure in embellishing [Monsplaisir,] so beautiful and so large,” with its “gardens, orchards and groves.” De Pradel received the highest compliment from Governor Kerlerec, who, after a lavish dinner party held at Monsplaisir in 1755, told him “that he did not regard my house as a provincial chateau, but as that of a farmer-general in the environs of Paris.”

My Pleasure indeed.

De Pradel died at Monsplaisir in 1764, after which an inventory was made of the complex. It described “a principal house divided into several apartments, gallery front and rear and across the ends… raised on brick [piers] with cellars, garrets, and storehouses underneath.” There were “glazed windows and casement doors” and fine hardware throughout. Nearby was what De Pradel had previously described as the ell: “another building[,] ninety-six feet long, ground floor in brick, gallery front and rear in which is a dining room, kitchen, laundry, wax works complete and other small apartments floored top and bottom, the whole well finished, locked with key.” A half-dozen dependencies and work sheds stood nearby, as well as slave cabins. Behind the complex were 40 arpents of croplands and forest, where an enslaved work force raised indigo and extracted timber, to produce the wealth De Pradel had enjoyed and showcased in Monsplaisir. The entire plantation went to his daughters, who sold it to Don Juan Lacou Dubourg in 1773, who sold it to Francois Bernoudy in 1779.

It’s around that time that Monsplaisir’s geography started to go bad.

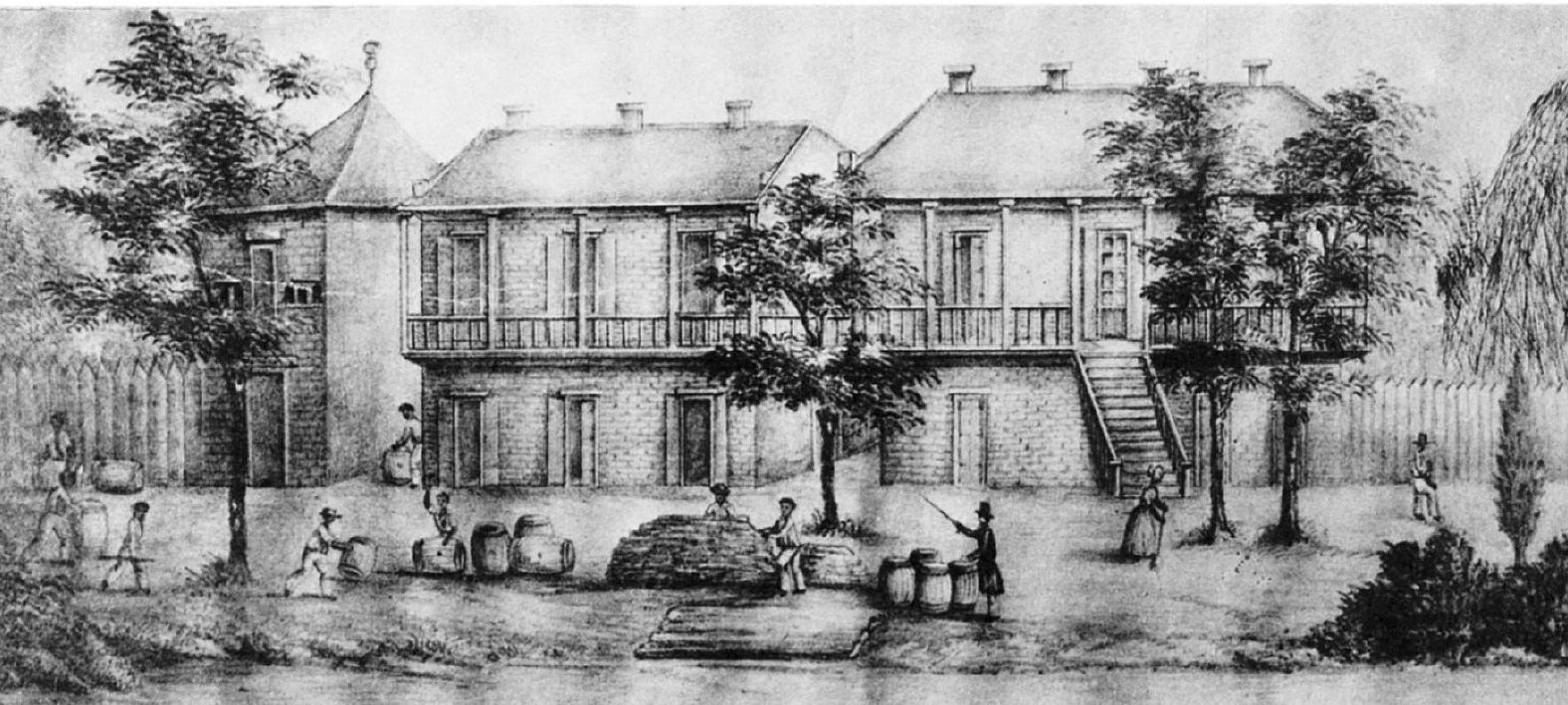

This lithograph of Monsplaisir was made about 1850. The home was purchased by John McDonogh in 1813. Image courtesy of the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians.

The problem was the Mississippi River. This part of the West Bank occupied the cutbank side of the crescent, where the river’s thalweg (deepest trench) leaned landward, and strong currents scoured bankside soils. This led to éboulis or éboulemens, meaning a cave-in or landslide of the river bank, which could lead to feared crevasses — “a fissure or breaking of the levée,” as a local writer explained in 1823. If severe, wrote another source that same year, “the waters rush [through] with indescribable impetuosity, with a noise like the roaring of a cataract, boiling and foaming, and bearing every thing before them.”

The East Bank also suffered cave-ins and crevasses, but not along the urban core, whose riverfront, particularly from today’s Jackson Square to Felicity Street, occupies the pointbar side of the crescent. There, water velocity slows, sediment drops, and battures (sandy beaches) form along the bank. The East Bank’s accretion corresponded to West Bank’s erosion, and few spots were more vulnerable than Monsplaisir’s.

In 1787, Bernoudy petitioned the Spanish Cabildo for a concession (land grant) elsewhere, as erosion threatened his frontage. Denied, he remained at Monsplaisir, and even as the bank steadily crumbled into the current, the complex retained its magnificence. Pierre Laussat, Louisiana’s last French colonial administrator, visited in 1803 and marveled “everything here was in the French style, even the old furniture, [with its] Parisian workmanship. No other residence in the colony was so elegant.”

Advertisement

In 1813, Bernoudy sold the plantation to a familiar name in local history: John McDonogh. Born in Baltimore in 1779 and apprenticed by a merchant, McDonogh made his way to New Orleans in 1800 and became a “mercantilist capitalist,” as historian Lewis E. Atherton put it, importing everything from hardware to liquor during the interregnum era, when Louisiana changed hands three times. His business interests amassed a fortune, but McDonogh was no ordinary businessman. An armchair philosopher with a worldly intellect, McDonogh by the 1810s wanted out of the rat race. He shifted his investment strategy to country real estate, and found the perfect place on the bucolic West Bank. In 1817, he took occupancy among the gardens and galleries of Monsplaisir.

His plantation, including an early village layout sketched by J.V. Poiter in 1814 (today’s McDonoghville, first subdivision on West Bank, predating the Algiers Point street grid), ran from what is now Homer Street at the riverfront down to present-day Hamilton Street. Over the next two decades, McDonogh incrementally expanded Poiter’s 1814 street grid, turning his enslaved agrarian operation into a residential neighborhood. He leased or sold parcels at reasonable rates to former slaves he had freed, the result of his moral grappling over of slavery and his dabbling into African repatriation schemes. In time, parts of this community would become known as Freetown, the first free black settlement on the West Bank and to this day a predominantly African-American neighborhood in adjacent Algiers. Monsplaisir served as iconic heart of the new community, at the riverfront between today’s Ocean Avenue and Hamilton Street — even as the scoring current inexorably encroached inland.

The gardens were the first to go. Monsplaisir itself was next. “Eventually the main part of the house was swallowed up by the river,” wrote Wilson. “The wing seems to have survived, probably moved to a safer location, and here McDonogh died in 1850,” after having written his famous will bequeathing the schools of Baltimore and New Orleans.

Relentlessly still shifted the Mississippi River. An 1853 account put the erosion of “the Mcdonough (sic) and Algiers,” and the accretion across the river, “at the rate of one square in ten or fifteen years.”

Advertisement

Eight years later, man’s folly gave nature a boost. Louisiana had seceded from the Union, and Confederate authorities had seized the enormous U.S. Marine Hospital in McDonoghville, built in 1834 near Monsplaisir and vacated for structural problems caused by a recent crevasse flood. They made the empty hospital into a storehouse for 10,000 pounds of gunpowder, in preparation for the defense of New Orleans in the ongoing Civil War. One night around Christmas 1861, the hospital “blew up with a report that shook the whole city to its foundation stones,” reported the Daily True Delta, shooting “a pillar of flame…illuminating the whole heavens.” The explosion, presumed to be the “diabolical work [of] traitors in our mist,” obliterated the hospital; even “the trees in the yard were broken, twisted and stripped as if by a hurricane.” The blast also tore open the levee and caused a flood of the McDonoghville riverfront.

By some accounts, the wartime rupture of the already-vulnerable levee spelled the end to the surviving wing and outbuildings of Monsplaisir. By other accounts, some components survived, only to be swept away by erosion in the 1870s. In any case, the entire circa-1750 complex is not only gone from the landscape, but wiped off the face of the earth. Pierre Laussat sensed as much during his 1803 visit. “Landslides caused by the river had already gouged out an arpent of land,” he recalled in his memoirs written 30 years later. The threat to Monsplaisir, he correctly predicted, was “only a few years away.”

De Patz’s environmentally sensitive design and raised construction did little to sustain Monsplaisir against its real folly of tenuous geography. If you want to see its site today, look about 2,000 feet straight into the Mississippi from the twin smokestacks of the Market Street Power Plant. It’s out there among the currents wending their way to the sea.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; Cityscapes of New Orleans; Bourbon Street: A History; and Bienville’s Dilemma. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements