This story first appeared in the March issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

What structure is most characteristic of New Orleans architecture? Most of us might cite shotgun houses, cast iron balconies, Italianate villas or townhouses with London-plan interiors. But if you’d put this question to Mark Twain, who visited in 1881, or just about anyone down to the start of the 20th century the answer would have been obvious, and by no means what architecture buffs swoon over: the utilitarian, usually ugly, but occasionally handsome, cistern.

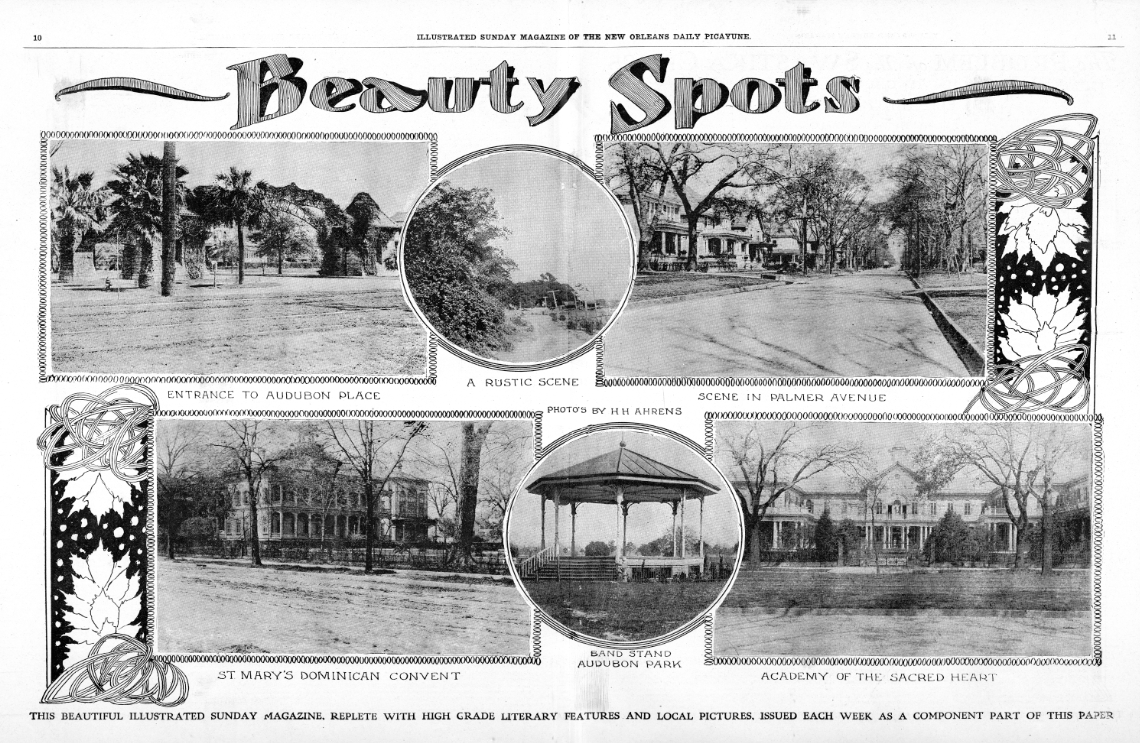

For a century and a half after the city’s founding, cylindrical wooden cisterns were everywhere. Most were elevated on plastered brick piers that rose three to six feet above the ground. Shotgun houses had them, factories had them, fashionable palazzos on Esplanade Avenue or in the Garden District had them, and public buildings had them. A couple of upscale residential architects strove to conceal them under the eaves, while in some public buildings they were hidden on the roof. A few were disguised under barnlike sheds. Most, though, were unapologetically placed in plain sight right next to the building. They ranged from four to eight feet in diameter and from five to 15 or more feet in height. Because they were often elevated above the ground on cylindrical plastered brick bases, their total height could reach even to the top of the second story, as was the case with the immense cisterns shown in several turn-of-the-20th century photographs. Locals were so accustomed to these now seemingly weird and ubiquitous tanks that they could ignore them, but their imposing presence made a powerful impression on visitors from elsewhere. Mark Twain, in his Life on the Mississippi, lavished praise on the city’s grand private residences but then went on to acknowledge grudgingly that, “One even becomes reconciled to the cistern presently; this is a mighty cask, painted green, and sometimes a couple of stories high, which is propped against the house-corner on stilts. There is a mansion-and-brewery suggestion about the combination, which seems very incongruous at first.”

Why didn’t New Orleanians get water for drinking and cooking from wells, like people elsewhere? In fact, most New Orleans buildings had wells to tap the abundant ground water barely six feet below street level. But New Orleans well water was murky and foul tasting, and remains so today. Beginning with the early settlers, New Orleanians therefore looked to rain water to meet their domestic needs.

Cisterns collected rainwater from the roofs of New Orleans buildings. By the early 19th century, several local firms turned out inexpensive cypress shingles, which were used to roof all but the most expensive structures. Fancy homes and public buildings were roofed with slate that arrived in New Orleans from Wales in the holds of cotton ships dead-heading back from Liverpool. Surrounding the roofs were wooden, and later, copper gutters, which channeled the water into pipes that led to the cisterns. When a cistern was full, an overflow pipe channeled excess water onto the lawn or into the street.

Because they collected water from the roofs, cisterns had to be very close to the main structure. It was this unavoidable feature that caused Twain to compare the houses-cum-cisterns to breweries. Cistern tanks were made exclusively from insect and rot-resistant, first-growth cypress wood. A rare exception is the large rectangular cast iron cistern, dated 1831, that can still be seen at the Hermann-Grima house at 820 St. Louis Street. The vertical staves of wooden tanks had to be carefully cut so they would fit tight together. They were then dried in the sun, so that when the tank was filled with water the staves would swell and create a leak-proof vessel. Iron hoops held the entire structure together.

In spite of these precautions, even the best constructed cisterns would start to leak after a few years. Various methods of caulking them were devised, but these, too, tended to have a short lifespan. Finally, in the second half of the 19th century, cistern builders began hedging their bet on cypress by lining the interiors of their products with a coat of coal tar. Not only did this retard leaks but it added a further layer of insulation, assuring that the cistern water would be relatively cool.

Cisterns constructed and maintained in this manner were by no means confined to New Orleans. They were equally common in towns like Thibodaux and Houma. Nearly all plantation houses depended on cisterns for potable water. The immense cistern that can still be seen at San Francisco Plantation is more elaborate and grander than most, but otherwise typical of rural cisterns situated on the Mississippi’s flood plain. Every locale had its own cistern builder, but the functional demands of the structures left little room for individual expression. Indeed, the only part of the cistern that allowed a degree of “art” was the top or cap. Most cisterns, both urban and rural, were flat and covered with boards or tin. But both in New Orleans and in the fancier plantation houses, multi-faceted caps or even fully rounded ones became de rigueur by the end of the 18th century. An example of this grander type of cistern was long on display at the Gallier House at 1132 Royal Street. Moved from the Gold Mine Plantation in St. John the Baptist Parish in order to preserve it, this fine cistern fell into disrepair and has now collapsed. With its graceful lines and turned, acorn-shaped finials, the top of this cistern looked like the domes of Baroque churches in Bohemia and Austria.

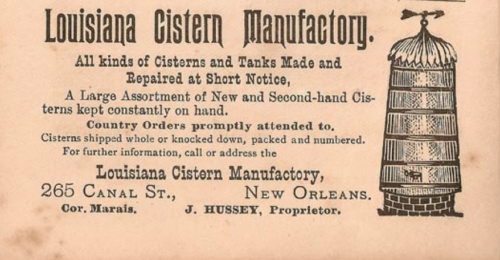

Because the process of construction was so similar to what was involved with making barrels, many early cistern builders were barrel makers. Over time the design, construction and installation of cisterns became an important and highly developed craft in New Orleans and throughout lowland Louisiana. By 1900, two dozen cistern builders regularly advertised their wares in the local press. The firm of Bigamer and Wahlig at 815 Julia St. promoted itself as the “Largest Cistern and Tank Factory in the South.” The relatively short lifespan of most cisterns assured a steady flow of business to the builders, which made the business lucrative for many. It was also highly competitive, as attested to by the numerous advertisements for cistern builders in local newspapers. Robert S. Brantley, in his book on architect Henry Howard, notes that Howards’ brother was in the cistern business. Every segment of the local populace produced cistern builders, who came to work hand-in-hand with the builders who designed and constructed most local homes and business buildings.

If outdoor cisterns were so numerous during the 18th and 19th centuries, why are there so few remaining in New Orleans today? What happened to the thousands of others depicted in maps, old photos and in notarial documents?

The simple answer is that on July 18, 1916, the Sewerage and Water Board issued an ordinance banning cisterns. Hundreds, if not thousands, were dismantled forthwith, and many others that were less visible to the prying eyes of inspectors ceased functioning, fell into decay and were eventually torn down.

But why did the government institute such a measure in the first place? Again, there is an obvious answer: by 1916, nearly all quarters of New Orleans were connected with city water. The idea of the city providing clean and potable water to the citizenry dates at least to the 1830s. However, until the mass production of cast-iron pipes began, this remained, as it were, a pipe dream. However, even before the Civil War, several major iron foundries had opened in New Orleans, mainly to serve the highly industrialized sugar industry. Following the war, foundries like the giant Leeds or McCann firms retooled to cast components for the iron balconies that protected pedestrians on many downtown sidewalks from the frequent rains. They also turned out luxury products like local ironwork firm, Wood, Miltenberger & Company’s “cornstalk fences” that later gained such fame. But their main products were pipes of all types and sizes. Mass production brought lower prices that greatly reduced the cost to the City for installing underground pipes for drainage, sewage, or tap water.

1. Cistern in the French Quarter, ca. 1880. Image courtesy Julie Couret.

2. Joined cistern tanks displaying highly ornamental caps, published as a stereoscope image by C. H. Graves Company in order to share a view of life in New Orleans, c. 1900. Courtesy of Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California at Riverside.

3. The cast iron cistern at the Herman Grima house was cast in 1831 by the E.E. Parker Iron Foundry, which occupied the present day site of the PRC.

4. Historic cistern at Manuel Andry Plantation house (demolished), located not far from Lombard Plantation and of a similar era. Courtesy of Alexander Allison Collection, Louisiana Division, New Orleans Public Library.

5. Advertisement published by New Orleans Business Directory, 1889.

In 1893, the City established a “Sewerage and Water Board” to improve the city’s drainage system and also to oversee the construction of underground pipes for potable water. In 1899, it hired a gifted young Tulane engineering graduate A. Baldwin Wood to design a drainage system and massive pumping stations that were to earn worldwide praise. By the new century, all New Orleans was abuzz with teams of workers digging trenches for storm and waste sewers and for the lines that provided tap water to households. The extension of water lines to newly formed streets opened new neighborhoods to settlement. The new water system had become so extensive by 1916 that the City could safely ban the further use of cisterns.

Thus, the destruction of cisterns was a celebration of victory by a city that had boldly embraced important new technologies in order to solve a grave problem that dated back to the city’s founding. But technological pride alone does not explain the draconian character of the 1916 ordinance that banned cisterns. After all, the city could have celebrated the new system of underground pipes that carried water to rich and poor neighborhoods alike, but otherwise left the cisterns to decay on their own.

The reason this course was not chosen is that since the foundating of their city in 1718, New Orleanians of all backgrounds had lived with a ‘sword of Damocles’ hanging over their heads. That sword was yellow fever. It is all but impossible today to appreciate the terror which this deadly scourge evoked among all segments of the public. Every few years since its founding in 1718, yellow fever had ripped through the city’s population, killing dozens, hundreds and even thousands in a single season.

The link between stagnant water and yellow fever was already understood. This understanding drove U.S. Army doctor William Gorgas to launch a war against swampy land in Panama, where Theodore Roosevelt was building his canal. In New Orleans, Dr. Rudolph Matas focused on draining swamps and pools of stagnant water throughout the area.

But no one had proven beyond doubt the link between mosquitoes and yellow fever. However, Walter Reed, a doctor with the U.S. Army, had been studying the research carried out in Cuba by one Carlos Findley. It was Reed who devised a simple but effective test to determine the link between mosquitoes and yellow fever. Placing one group of subjects in an unscreened room where hundreds of the mosquito breed aedes aegypti buzzed, and a second group in an adjacent screened room that was free of mosquitoes, Reed watched as several people from the first group came down with the disease, but none from the second. By this simple test Walter Reed demonstrated beyond all doubt that mosquito bites accounted for the spread of yellow fever.

As nearly 500 New Orleanians were dying in 1905, the Health Department issued its Biennial Report of the Board of Health of the City of New Orleans. For the first time, the report presented mortality statistics on yellow fever over the preceding decades. It reported that in 1853, 7,849 New Orleanians had perished, while in 1858 the total reached 4,849 and in 1867 it was 3,167. The number of victims fell during the epidemic of 1873 but the death toll soared again to 4,046 in 1876. By the turn of the century, yellow fever epidemics were becoming a thing of the past in most parts of the United States. But in New Orleans “Yellow Jack” claimed 298 victims in 1898. And in 1905, the year the report was issued, it killed 437.

The appalling totals squelched any euphoria over technological progress and forced the city to face reality. The first step in New Orleans was to require all cistern owners to place screens over the tops of the tanks. However, large numbers of citizens simply ignored the ordinance. In an attempt to make an example of scofflaws, the government fined 25 citizens of Carrollton for failing to put screens on their cisterns. Some of those who refused to install screens did so in the knowledge that an outright ban was under consideration at the same time. Why, they reasoned, should they screen their cisterns if they would then have to tear them down? They were right. On July 18, 1916 the City issued a categorical order to all citizens banning cisterns and indicating that anyone not complying would face a stiff penalty. Ike Feitel on Tulane Avenue and a host of other tradesmen immediately placed ads in the main newspapers offering to remove cisterns for $25.

Most New Orleanians complied with the ordinance, but thousands objected. By the following spring, Board of Health inspectors had identified 1,500 non-complying property owners and prepared to fine them all. Most were homeowners. Indignant opponents of the ordinance immediately instituted a lawsuit against the Sewerage and Water Board, claiming that the Sewerage and Water Board had exceeded its legal mandate. Leaders of the group boisterously declared that they were prepared to appeal a negative decision to the Supreme Court of Louisiana. Meanwhile, cistern builders, acting on the slim hope that the Supreme Court would overturn the ordinance and save their businesses, continued to place ads in the local press. But Judge Donahue of the Second City Criminal Court nipped the legal challenge in the bud when he ruled that the ordinance was fully consistent with the law of Louisiana and sealed his judgment by citing a barrage of laws and ordinances. It took only a few more years after the passage of the ordinance for cisterns to become extinct in New Orleans and their very existence a distant memory.

- Reconstructed cypress tank cistern at Lombard Plantation House, 3933 Chartres St. Made by master craftsman, Brandon Begnaud of Breaux Bridge, LA. Shown with author Frederick Starr.

- Reconstructed cistern at its precise original location behind Lombard Plantation house.

In 1988, the two authors of this report set about restoring the main house of the historic Lombard Plantation at 3933 Chartres St. in Bywater. Through several strokes of good fortune, Fred Starr was able to acquire the front yard and nearly an acre of the former dooryard garden behind the structure. In due course, we carried out a meticulous restoration of the main house, reconstructed the kitchen building, and discovered and reopened the original plantation well. In the course of this work we noticed that an 1843 plan of the territory preserved in the New Orleans Notarial Archives indicated the precise location of the former cistern and the diameter of its base. Inspired by this chance discovery, we decided to rebuild the cistern. Doing so, we reasoned, would enable one to see the historic main house in its full context, (i.e., as it appeared in 1825 when Joseph Lombard Pere, a native of France, commissioned architect-surveyor Joseph Pilie to design and construct it for his newly married son and daughter-in-law).

Although we knew the size of its base, we had no plan of the tank or the top that surmounted it. Happily, we found 19th century photographs of a number of nearby plantation houses that showed cisterns. Typical was the cistern that supplied water to Manuel Andry’s plantation house, which stood where the Industrial Canal is today. All were nearly identical. They were raised on four-foot high plastered brick bases and featured impressively tall tanks that added from six to 12 feet to the height. All were crowned with an ornamental finial. Was it possible that they were all constructed by a single cistern-builder?

It was our good fortune to learn of Mr. Brandon Begnaud, a master craftsman who carries on the nearly extinct art of building handsome eight-foot tall cypress and iron “rain barrels.” Mr. Mark Elias constructed a handsome cap of wood that was then covered and waterproofed, while the Clesi family not only turned the finial but carried out other critical tasks. A neighborhood craftsman, Mr. Paco Gomez, constructed a hinged door for the base and helped install the structure.

The whole process turned out to be unexpectedly intricate and time consuming. But after three years of trial and error, the cistern is now up—but not running. Since the 1916 law remains in force, we knew that we could not fill the cistern with water. Indeed, the pipe that would have sent water from the roof gutter to the tank is in fact a dummy not connected to the cistern. But the Lombard cistern again stands proudly where it stood nearly two centuries ago. Its reconstruction completes the restoration of a rare West Indies-style Creole plantation house. It is a living reminder of what had once been a ubiquitous feature of New Orleans buildings. And as one inspects this substantial and supremely functional structure, one is reminded of the technological improvements and medical breakthroughs that rendered the original cistern on the site obsolete and doomed every other cistern within the borders of New Orleans.

Spigot and Cap – before covering and painting – of a reconstructed cistern at Lombard Plantation house.