This story appeared in the October issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

A tale of three buildings

What do the Cabildo, Gallier Hall and the Bradford-A.P. Tureaud Building have in common?

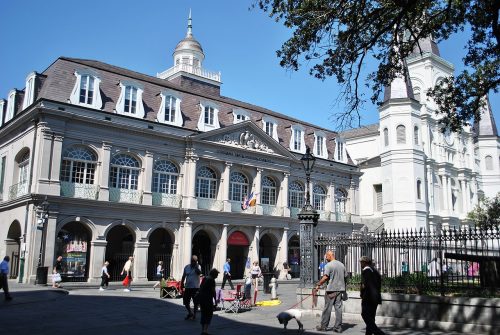

They date from different eras. The Cabildo, located in Jackson Square to the left of St. Louis Cathedral, is one of New Orleans’ earlier extant structures, built between 1795 and 1799. Construction began on Gallier Hall, the stately former City Hall building, in 1853. And the Bradford-A.P. Tureaud Building, a beautiful blond brick structure that’s now home to the New Orleans Culinary & Hospitality Institute, was erected in 1916.

They have different styles, naturally, as their construction took place in three different centuries. The Cabildo has prototypical Spanish Colonial features, including an arched colonnade and fan-light windows; a later addition brought the French mansard roof. Gallier Hall is the epitome of the Greek Revival style. And the Bradford-A.P. Tureaud Building at 725 Howard Ave., fitting for its era, is a large, commercial interpretation of the Arts and Crafts style.

And they are located in different parts of the city. The Cabildo is, of course, in the Vieux Carré, while the other two are located in the Lafayette Square neighborhood.

So what could these buildings possibly share in common?

They were all once proposed for demolition.

1: The Cabildo. Photo by Elisa Roll. 2: Gallier Hall. Photo by Davis Allen. 3: The Bradford-A.P. Tureaud Building, which now houses the New Orleans Culinary & Hospitality Institute. Photo by Liz Jurey.

These three buildings have varying degrees of notoriety. The Cabildo is part of Jackson Square, which serves as the global image of the City of New Orleans. It’s recognized the world over, and today is part of the Louisiana State Museum, visited by millions of people a year.

Gallier Hall is locally famous, both by those who remember its reign as City Hall, which ended in 1958, and by those who enjoy its beauty today, admiring the edifice from Lafayette Square Park or during a Mardi Gras parade or Luna Fete. The Bradford-A.P. Tureaud Building has become more well known in recent years thanks to an extensive renovation for NOCHI.

It’s hard to imagine New Orleans without even one of these buildings. And yet all three were seriously threatened with erasure from our city’s landscape.

That’s not their only similarity, though. They were all saved thanks to passionate residents who cared about the buildings’ pasts and their potential futures, and they all were restored to serve the city’s residents for decades more.

Advertisement

The salvation of the Cabildo is one of the earliest examples of a historic preservation movement in New Orleans. After its construction was complete in 1799, the Cabildo served the Spanish government, the city and the state in varying functions: as a seat of government, as City Hall and as various courts. Maintenance on the structure was lacking, and by 1892, its shabby appearance led a Louisiana Supreme Court justice to deem it a “half-ruined, ramshackle and inadequate old building.” Distaste for the Cabildo and its sister structure the Presbytère grew, and in 1895, the New Orleans City Council called for both to be demolished so that modern and more spacious court buildings could be built in their place.

The plan drew immediate public protest. Many residents, lawyers, architects and artists objected to the demolition. The fight was fierce, but an alternative plan for the buildings ultimately helped lead to their salvation: They would serve as the new home of the Louisiana State Museum, which was established in 1906 and moved into the buildings in 1911. Today, the Cabildo is a National Historic Landmark.

Shortly after its 100th birthday, Gallier Hall’s future was questioned as a new City Hall was constructed nearby on Duncan Plaza. City officials figured the old building to be useless and outdated compared to the new, mid-century modern-style City Hall. The Louisiana Landmarks Society had hosted an exhibit about Gallier Hall in 1950 to raise appreciation for the structure’s storied history, but by 1958, the organization had to fight mightily to save it from the wrecking ball. The preservation of Gallier Hall was an early and important success by Landmarks.

Gallier Hall was named a National Historic Landmark in 1974, but city officials still neglected to maintain the structure for decades. Former Mayor Mitch Landrieu, as part of the city’s tricentennial celebration in 2018, raised millions for its restoration, and today Gallier Hall gleams once again.

The Bradford-A.P. Turead Building was proposed for demolition in 2000, when the Arts Council of New Orleans sought to acquire the site for its new headquarters. However, the plan wasn’t as widely fought as the demolitions proposed for the Cabildo and Gallier Hall. The structure had been covered by an unsightly metal sheathing for decades, and many residents had forgotten about the beautiful brickwork underneath.

Politicians, historians, preservationists and others debated about what was really under the panels as demolition plans moved forward. Once the sheathing began to be stripped away, the original building, largely unharmed, started to peek through.

Advertisement

“Its nice façade was discovered once [the building cover] was scraped away,” Tracy Lea, principal at architecture firm Eskew+Dumez+Ripple, told Preservation in Print in 2018. “It put the project onto a different schedule.” Suddenly, the building was acknowledged by all as something worth saving.

The Howard Avenue building was renovated, its façade restored and the interior outfitted for use by the arts organization. Full occupancy never happened, however; funding for the project ran out, and it sat empty for years. After another renovation, the building today has a wonderful new life as NOCHI.

There are so many reasons historic preservation matters — the most important include the economic value of preserving our city’s character, the moral obligation of honoring our history and the environmental imperative of reusing buildings (the ultimate form of recycling). There is no question that saving our built environment has made New Orleans the unique place it is today.

These reasons for saving buildings are widely agreed upon. And yet many of this city’s historic sites are still threatened. We have to fight continually to ensure historic structures are spared demolition.

In this issue of Preservation in Print, you will read about several other buildings which were spared the chopping block and restored for productive uses. We are inspired by these stories of triumph, and we hope you will be, too.

This is the PRC’s mission. Thank you for supporting our work for 46 years, and thank you for fighting alongside us. Historic preservation is as relevant today as it was in the 1890s when the Cabildo was threatened.

Our work is a continual evolution as to the “how” of historic preservation, but the “why” remains the same. These buildings teach us about our past to lead us into a bright future. And they make New Orleans truly one of a kind.

Danielle Del Sol is the Executive Director of the Preservation Resource Center.

Advertisement