This story first appeared in the December issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Revitalizing the upper floors of lower Canal Street: it has been a dream of urbanists ever since those storehouse stories went dark decades ago. Recent efforts by the City Planning Commission and an upcoming project by the Preservation Resource Center and the Downtown Development District now aim to make it happen — be it for residency, office space, commerce or short-term rentals.

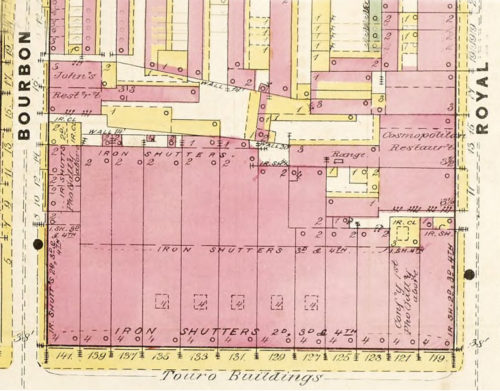

No better block speaks to how the upper stories of New Orleans’ premier downtown commercial artery used to be occupied than the keystone 700 block of Canal between Royal and Bourbon, arguably the city’s three most famous streets.

Canal Street dazzled the eye in the late 19th century. As the region’s showcase retail emporium, the 171-foot-wide boulevard boasted magnificent window displays of world imports, glowed with early electrical lighting and bustled with streetcars and fancy hackney cabs, not to mention ferries and steamboats docking at its riverfront foot.

The street’s name and capacious width came from an 1807 Act of Congress which reserved a 60-foot right-of-way in a street grid to be surveyed into the former commons between the old fortifications and present-day Common Street. The corridor would host a navigation channel to be dug connecting the Carondelet Canal turning basin on Basin Street with the Mississippi River. After the grid was laid out in 1810, creating today’s Canal Street, authorities had second thoughts about the channel due to technical concerns regarding the lock.

Advertisement

Gratefully, the project was abandoned; a navigation canal here would have cleaved the city in half and could have been disastrous. Yet the name stuck, and we still call it Canal Street today.

While its early years saw predominantly residential land use, Canal Street transformed to mostly retail as New Orleans grew and downtown bustled with economic rigor. A walk up the grand artery 150 years ago would have presented a literal and visual cacophony. Buildings, while consistently ornate, varied widely in style, and their façades jutted intermittently into the streetscape. Awnings and verandahs of different sizes, loud with advertisements, jockeyed for attention amid protruding signs and hanging flags, all below a parade of pediments, finials, turrets, cupolas and domes. The Canal Street panoply of architecture was diverse, intricate and busy to the point of delirious.

One particular block, however, would have stood out for its singular and integral design: a row of identical storehouses unified by perhaps the most splendid cast-iron gallery ever seen in New Orleans. It was known as Touro Row, and it occupied every inch of Canal from Royal to Bourbon.

Touro Row in the 1880s. Detail of photo by George Francois Mungier. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

Touro Row in the 1880s. Detail of photo by George Francois Mungier. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

Touro Row honored Judah Touro (1775-1854), the famed merchant-turned-philanthropist and benefactor of New Orleans’ Jewish community, among others. Touro had invested in and around this area throughout the 1840s, buying up properties as they came on the market. In 1847, he acquired a key parcel at the corner of Bourbon, which was occupied by the Ionic-style Episcopalian Christ Church, designed by architects Gallier and Dakin and completed 10 years earlier. The Episcopalians having departed for Uptown, Touro converted the imposing temple into a shul for his Dispersed of Judah congregation, and adjoined it with a Hebrew school as well as his own residence in the former church rectory.

All along, through his Jewish Benevolent Association, Touro had been replacing older buildings farther down the block with identical units of three-bay Greek Revival storehouses designed and built by Thomas Murray, presumably with the goal of filling the entire block. Four stories in the front, two in the rear, more than 100 feet in depth, and with internal iron shutters for fire control, the buildings were state-of-the-art. Murray in 1851 had also erected six similar buildings for Touro on the lake side of what is now 300 St. Charles Ave.

Canal and Bourbon by this time had been steadily shifting to more commerce and congestion, and, finding the din incompatible with study and worship, the Jewish congregation soon followed the Episcopalians’ footsteps and also relocated Uptown. The synagogue was razed, making room for three more storehouses at the corner of Bourbon Street, completed in October 1855.

Additional units arose, leaving one last older building standing, Judah Touro’s mid-block residence, perhaps out of respect for the philanthropist after his death in 1854.

The man now steering the project was Touro’s universal legatee (legal successor), Rezin Davis Shepherd, an old friend who had helped Touro recover from a grievous injury suffered during the Battle of New Orleans. Shepherd had installed atop the 11-unit complex a plaque that read “Touro Buildings, 1856.” Shortly thereafter, Touro’s home was removed, and the 12th and final unit was erected in its space in 1857.

Nicknamed “Touro Row” or “Touro’s Row” as early as 1853, the dozen edifices were handsome if rather staid representatives of the Greek order, designed for commerce on the lower floors and offices or residences above. What made Touro Row distinct was its breathtaking, 360-foot-long cast-iron filigree double gallery, installed unit-by-unit to form a symmetrical whole. It even wrapped around the Bourbon and Royal corners and continued 100 feet into the French Quarter, making the full span over one-tenth of a mile long.

- Touro Row in 1876; Sanborn Map courtesy of the Tulane Southeastern Architectural Archive

- Touro Row around 1890. Detail of photo by George Francois Mugnier. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

Located in the absolute heart of the booming metropolis, Touro Row helped permanently shift the city’s primary retail axis from Chartres and Royal streets, where shops had clustered for decades, to Canal Street, where it would remain for the next century. The dozen buildings, numbered at the time as 119-141 Canal St., were home to scores of stores on the ground floor and various offices above, with a specialization in musical instruments and sheet music shops, including Grunewald’s and Werlein’s.

Touro Row’s gallery, along with that of the Pontalba Apartments installed a few years earlier, helped make cast-iron ornamentation en vogue, and similar verandahs would appear throughout downtown, eventually becoming part of the city’s iconography.

Just before the Civil War, Shepherd sold Touro’s Row to Brooks and Brooks of Boston, which in 1887 sold it for the tidy sum of $335,000 (nearly $9 million today) to a syndicate of local investors. The transaction was seen as a harbinger of good news for the downtown commercial real estate market. “The property has (long been) regarded as the most eligible in New Orleans for business purposes,” wrote the Daily Picayune, “and the sale naturally was the topic of conversation among business men yesterday…. New Orleans is going to boom!”

Advertisement

Boom it did, but not in a good way. Late on the night of Feb. 16, 1892, after what the Daily Picayune described as “a ceaseless procession [of] merry, happy” people patronizing “saloons [and] restaurants,” a fire ignited across Bourbon Street from Touro Row. The flames “crossed the street in a bound” and enveloped adjacent buildings. Steam pumps arrived to shoot water beyond the inferno, controlling its spread and letting it burn itself out.

By morning, Bourbon at Canal was one gigantic smoldering heap of ash and melted iron. The $2 million of damages included 13 major business enterprises operating out of three destroyed Touro Row units plus adjacent storehouses.

Other units might have been lost were it not for their iron shutters. It was nonetheless one of the worst downtown blazes since colonial times, and while new buildings were constructed shortly thereafter using insurance proceeds, Touro Row had been permanently disfigured. The replacement units were taller and stylistically mismatched from the rest of the row.

Three units of Touro Row survived the 1892 fire and still stand today at 701-707 Canal St. Photo by Liz Jurey.

The 1892 fire incised a structural variability into the Bourbon Street-end of Touro Row that is visible to this day. It opened up an opportunity for Royal Street’s Cosmopolitan Hotel to expand clear through to Bourbon, and when that annex was demolished in 1953, it allowed for the extension of Woolworth’s Department Store, formerly Kirby’s, from its Canal Street frontage back onto busy Bourbon. Woolworth’s closed in the late 1990s, and in 2000, its space was cleared and reoccupied by the high-rise Astor Hotel, now the Crown Plaza. By this time, most commercial activity in Canal Street storehouses had dropped down to the street level, and upper floors went dark and decrepit.

The Royal Street end of Touro Row, having been spared the fiery trauma of 1892, survived and remained stable. The three units near the corner today (701-707 Canal St.) retain their more-or-less original façades, although the original cast-iron gallery is gone, the victim of scrap-metal drives and street-front modernization. Four mid-block units have been incorporated into the Astor Hotel, and at least five of the original 12 units still retain their slightly hipped roof profiles.

Had Touro Row survived as an integral row with its splendid double gallery, it would have become one of the most famous streetscapes in the city. Given the vagaries of downtown real estate, we are fortunate to retain about half of Touro Row today, even more so if the upper floors of 701-707 Canal see revitalization. That was the happy fate of Judah Touro’s “other” row, a line of circa-1850s storehouses recently restored on 301-313 St. Charles Ave.

Touro Row in November 2018. Photo by Liz Jurey.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and the author of “Cityscapes of New Orleans,” “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma” and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

PRC has teamed with the Downtown Development District on a new project to revitalize the upper floors of Canal Street buildings. Stay tuned – more details on this project will be released soon!

Advertisements