This story appeared in the February issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

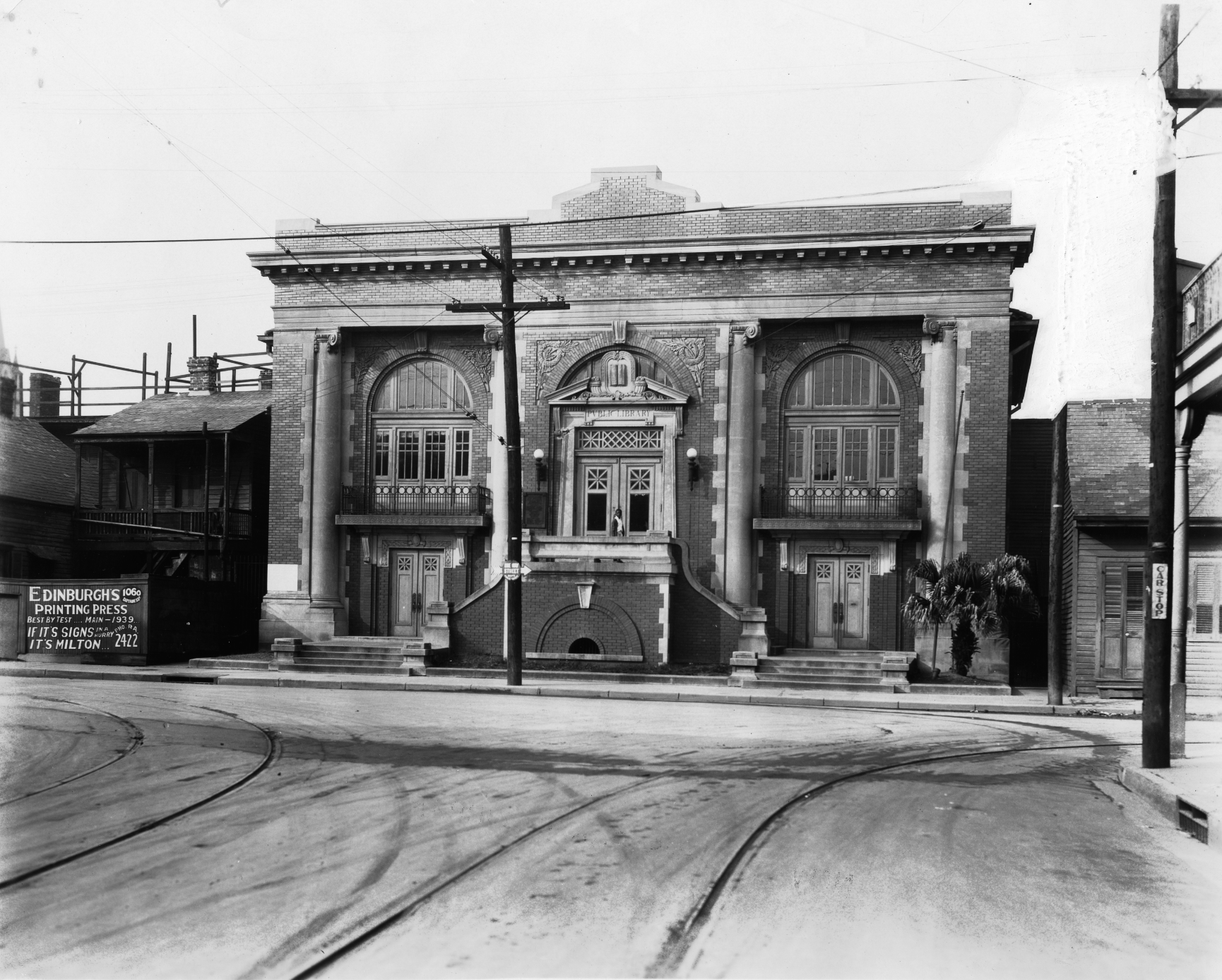

It felt like we were extras in a scene from a science fiction movie, the kind in which all the people are gone and only the buildings remain. As my wife Paula and I crossed Venice’s Piazza San Marco — one of the most iconic bucket-list destinations in the world — we passed under an azure Italian sky, and counted exactly four other people in the two football fields of open space between the upscale shops and St. Mark’s Basilica.

It was June 2020, our fifth trip to Venice in four years. So we knew what a typical lunchtime in Piazza San Marco is supposed to look like: maybe 12,000 people or more, a mix of cruise ship passengers, day trippers from the Italian mainland and overnight tourists, jammed elbow to elbow into the square, taking selfies as they inch past the long lines at the spectacular Byzantine basilica and the towering Campanile, then around the corner, past the Doges Palace, toward the southern entrance of the Grand Canal. Hundreds more normally fill up the outdoor tables at the tourist cafés, where they sip overpriced Aperol Spritzes and watch the other tourists watching them.

Advertisement

But on this day in June, it was pretty much just us. And it felt like a miracle.

Granted, this particular miracle was driven by the worst global pandemic since 1918. And we were some of the first non-Italian tourists to visit Venice since COVID-19 wiped out most of the world’s tourism industry. In what is generally regarded as the most over-visited city in the world, we were certainly the first Americans most hotel and restaurant workers had encountered in four months.

One strange byproduct of the pandemic was that every bar and restaurant’s outdoor tables were full of happy locals, who could wander their city and enjoy its gifts free of the tourist crush for the first time in memory. The lack of tourists also gave us the time and space to ponder the worst threat presented by global tourism: tourists.

But the locals we talked to admitted it was complicated. They enjoyed having their city back. But they knew the economic future of their city depends on the tourists returning. Or, at least, some of the tourists.

Venice’s St. Mark’s Square, one of the most iconic sites in the world, is normally wall-to-wall with tourists. But during the pandemic, the square is often deserted, even at the peak lunch hour. The lack of tourists is a respite for Venetians, but devastating to the local economy.

To be a conscious traveler is to be acutely aware of the threat presented by people like us. And months of not being able to travel has given us all the time and space to think about whether there might be better ways to be a traveler.

When we travel, we go out of our way to try to distinguish ourselves from all the uncaring herded masses, tromping through sites and souvenir shops, following the flag-waving tour guides and posing with selfie sticks. We tend to stay in a place for days, not hours. We want to know not just the sites, but the people, the food, the culture, the history. We’re “good” travelers.

But in the end, we are taking up space and spitting out carbon, just like the others. We lean toward locally run hotels, but we’ve stayed in our share of gentrifying Airbnbs, responsible the world over for driving working-class people out of city centers. And we once paid to join a tour group for the Vatican Museum just to skip the overcrowded lines, then fled the tour as soon as we got in the doors.

We may be less of a problem than many. But we are not the solution.

And yet, Venice is one of our favorite cities in the world. Architecturally speaking, it may be the most important living — and lived-in — museum of beautiful human creations on earth, dating as far back as the 13th century. Everywhere you turn, there is a masterpiece of breathtaking beauty.

And all of it is gravely endangered. The entire Grand Lagoon is now regarded as among the most endangered heritage sites in Europe.

More than 25 million visitors a year to Venice put an incredible strain on the locals who try to live within the boundaries of the ancient city. So the pandemic-reduced crowds gave many an opportunity to revisit their favorite restaurants, meet with old friends and walk their favorite routes in the city unfettered. As it emerges from the pandemic, Venice is trying to find a new balance between economic vitality and the city’s livability.

We moved from New Orleans to France in 2017, which means that Venice is now just a day’s drive away from our home in Burgundy. Every New Orleanian we know who has been there loves Venice, and it’s easy to understand why. The city is sinking, giving it a sense of impermanence and its residents a sense of laissez les bons temps rouler (while you still can). It has many problems, and a history of corruption. Its tourist hordes make many people disdain ever visiting it again, labeling it crowded or dirty or any one of a multitude of insults that just reveal the visitor’s narrowness of vision. And it’s a city with an inextricable relationship to the rising and falling of the sea.

So like New Orleans, to love Venice is to see the beauty and forgive the problems. But like a lot of beautiful places in the world, Venice is literally being loved to death.

What, then, shall we do?

First, traveling the world is the province of the privileged, and, compared to most of the world, the well-off. Therefore, it is incumbent upon those of us who travel to start providing not just a decent living to small business entrepreneurs, restaurateurs and shop owners, but also to provide the means for preserving and restoring that which we are loving to death. For example, no day trips. Stay awhile. Spend some money. Get to know the place and its people.

Advertisement

As overrun cities become more unlivable for the locals, we must support efforts to make life in those cities more friendly, more livable, more sustainable. And we have to figure out ways to make our visits co-exist with the local way of life, lest we destroy the very qualities that made us want to visit, and end up just as groups of tourists watching other groups of tourists, like Bourbon Street on a Saturday night.

In Venice, that means supporting the decision by Venetians to begin charging day visitors up to $11 a visit, depending on the day and season. Overnight guests with a hotel room (or presumably a short-term rental) will be exempt. It won’t stop the cruise ships, but at least it’s a step toward funding restoration and preservation efforts. Those who are threatening the city must pay for its protection.

These efforts at sustainable living are spreading, and those of us who travel should applaud them — even when it makes visiting more inconvenient.

The mayor of Paris continues to make friends in town and enemies in the suburbs with a transformation of the City of Light into a bike-friendly urban zone, which has been accelerated by the pandemic. Roads along the Seine are already closed to cars, and the pandemic allowed for experimentation: closing to automobiles the heavily traveled Rue de Rivoli, which cuts through the 1st arrondissement in the heart of the city. Only cyclists, pedestrians and buses are allowed. This is bound to make getting around more difficult for the 30 million visitors each year. But it will make the city cleaner, more livable, less noisy, more sustainable.

The Rue de Rivoli, normally a car-clogged main artery through the heart of Paris that passes by City Hall and the Louvre Museum, was closed to all but bicycles and electric scooters this summer as part of the mayor’s effort to turn Paris into a cycling city on par with places like Amsterdam.

Barcelona is also transforming its city center into pedestrian-friendly car-free zones using the “Superblock” concept of urban redesign that has greatly reduced automobile traffic downtown and made the city more attractive for its residents. It may be less friendly to door-to-door Uber service and the gathering of tour buses and other tourist-driven traffic in the city center. But again, it helps to preserve the things that make Barcelona worth visiting in the first place.

As the vaccine era begins, these are issues that New Orleans must continue to grapple with as well. Like Paris, Barcelona and Venice, the city should seek creative solutions that extract a cost from all of the stakeholders, but benefit the city as a whole.

I live too far away now to take a firm position on the latest proposal to limit vehicular traffic in the French Quarter. But, based on what’s happening elsewhere in the world, I can say it’s not crazy. Support for sustainable tourism will require creative, out-of-the-box thinking that should be seriously considered, and not rejected out of hand simply because powerful stakeholders will be inconvenienced.

A lingering question as we emerge from the COVID-19 era and enter the vaccine era is this: Do we really want everything to return to normal? Or do we want to take the opportunity of a year-long pause in business-as-usual to think creatively about how we can make the world a better place than it was before the pandemic?

“We need tourists to come back to Venice, but we don’t need things to be like they were before,” said Peter, the masked owner of one of our favorite restaurants, as we ate a safely distanced dinner outdoors along the Dorsoduro Canal on the northern edge of central Venice. “If we don’t make changes, we’re not going to survive.”

James O’Byrne, an award-winning journalist who worked in New Orleans for 36 years, now writes and travels with his wife, Paula, from their home in Burgundy, France. Follow them at travelersforlife.com.

Advertisements